INTRODUCTION: ROBOTS

Robots are not a modern concept. They are as old as pottery at the very least.

Once human beings learned to fashion objects out of clay and bake them hard--especially objects

that looked like human beings--it was an easy conceptual leap to suppose that human beings themselves

had been fashioned out of clay. Whereas ordinary lifeless statues and figurines needed nothing more than a

human potter, the more miraculous human body, living and thinking, required a divine potter.

Thus, in the Bible, God is described as forming the first man, potter-wise, out of clay. “And the

Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man

became a living soul.” (Genesis 2:7)

In the Greek myths, it was Prometheus who fashioned the first human beings out of clay and water

and Athena breathed life into them. No doubt one could go through the myths of many nations and find

gods busily making little statues that became human beings.

What’s more, the gods continued making living things or quasi--living things later on. With time,

of course, human beings learned that clay was not the only building material, but that metals were superior,

so that the divinely created beings came to be thought of as metallic in nature, and no longer as pottery.

In the eighteenth book of the Iliad, for instance, Hephaistos, the divine smith, is forging new

armor for Achilles, and he is described as having “a couple of maids to support him. These are made of

gold exactly like living girls; they have sense in their heads, they can speak and use their muscles, they can

spin and weave and do their work.” Hephaistos was also described as having formed a bronze giant, Talos,

that served to guard the shores of Crete by walking around the island three times a day and repelling

anyone trying to land.

Folk tales and legends of all nations tell of objects, usually considered inanimate, that through

magic of one kind or another, achieve human or even superhuman intelligence. These can vary from the

“golem,” a giant made of clay, supposedly given magical life by a rabbi in sixteenth-century Bohemia,

down to the magic mirror in “Snow White” who could tell “who is the fairest of them all.” Various

medieval scholars, such as Albertus Magnus, Roger Bacon, and Pope Sylvester II were supposed to have

fashioned talking heads that gave them needed information.

Human beings, of course, tried to devise “automata” (singular “automaton”--from Greek words

meaning “selfmoving”) that would work through springs, levers, and compressed air rather than through

magic, and give the illusion of possessing purpose and intelligence. Even among the ancients were those

who possessed sufficient ingenuity who could make use of the primitive technologies of those days to

construct such devices.

The breakthrough came, however, with the development of mechanical clocks in the thirteenth

century. Clever technologists learned how to use “clockwork”--gears, wheels, springs, and so on--to

produce not merely the regular motion of clock hands, but more complex motions that gave the illusion of

life.

The golden age of automata came in the eighteenth century, when automata in the shape of

soldiers, or tigers, or small figures on a stage could mimic various life-related behavior. Thus, Jacques de

Vaucanson built a mechanical duck in 1738. It quacked, bathed, drank water, ate grain, seemed to digest it,

and then eliminated it. It was all perfectly automatic, of course, and without volition or consciousness, but

it amazed spectators. In 1774 Pierre Jacquet-Droz devised an automatic scribe, a mechanical boy whose

clockwork mechanism caused it to dip a pen in ink and write a letter (always the same letter, to be sure. )

These were only toys, of course, but important ones. The principles of automata were applied to

automatic machinery intended for useful purposes, which led to the invention of punched cards in 1801,

which in turn set the feet of humanity on the path toward computers.

The Industrial Revolution, which had its beginnings as the golden age of automata came to an end,

was therefore a continuation of the notion of the mechanical production of apparently purposive behavior.

As machines grew more and more elaborate, the notion that human beings could eventually construct

devices that had some modicum of human intelligence grew stronger.

In 1818 a book by Mary Shelley was published that was entitled Frankenstein and that dealt with

the construction of a human body that was given life by its inventor. It was subtitled “The New

Prometheus” and has been popular ever since its appearance. In the book, the created life-form (called “the

Monster”) took vengeance on being neglected’ by killing Frankenstein and his family.

That is considered by some to have initiated modern “science fiction,” in which the possibility of

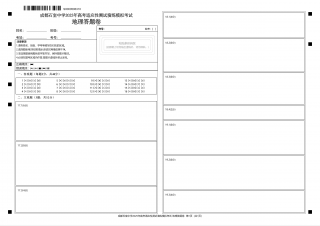

2024-12-08 12

2024-12-08 12

2024-12-08 14

2024-12-08 14

2024-12-08 10

2024-12-08 10

2024-12-08 10

2024-12-08 10

2024-12-08 15

2024-12-08 15

2024-12-08 18

2024-12-08 18

2024-12-08 27

2024-12-08 27

2024-12-08 25

2024-12-08 25

2024-12-08 16

2024-12-08 16

2024-12-08 30

2024-12-08 30

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394