Jack L. Chalker - Soul Rider 2 - Empires of Flux and Anchor

VIP免费

2024-12-04

1

0

1.15MB

134 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

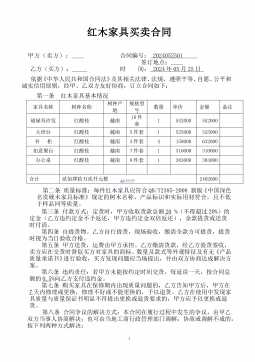

SOUL RIDER II:

EMPIRES OF FLUX AND

ANCHOR

Jack L. Chalker

Copyright © 1984 by Jack L. Chalker

ISBN: 0-812-53-277-5

e-book ver. 1.0

For Somtow Sucharitkul

a spectacle of unmitigated horror

with a dash of Bakti

1

RECALCITRANT GODS

Gods do not normally expect to look out the windows of their palatial heavens and see an

enemy army advancing.

Gyasiros Rex, Lord of Yalah, god and king in one, watched the forces advance and tried to

think of what to do. His all-seeing eyes showed him the scope of the encirclement, despite the

fact that the nearest enemy trooper was a good hundred kilometers away, but the fierce

determination in the would-be attackers did not worry him. His Fluxland kingdom had an energy

shield impenetrable to all except those he, as a god, might choose to admit, and it had been placed

there by the sheer force of his will. Neither the troops nor their weapons could pass that shield

until and unless it was broken down.

The tremendous power that Flux gave to selected individuals always seemed either to corrupt or

drive the wielder of such power into some unique form of madness. Gyasiros had been born in

Flux and trained as a wizard in the great magical university at Globbus, where he'd shown

exceptional power in taking the raw energy that was the Flux itself and transforming it and all

inside it as he willed. He was certainly a god in his own Fluxland, his power there absolute, and

he loved it. Not merely political power; the very trees, rocks, animals, and even the sky were of

his design and his to create, destroy, or alter as his mood moved him. He was worshipped by his

people, who knew, too, that divine will rewarded the faithful and punished the transgressor.

He liked things this way, and he was in no mood to change or accommodate to anyone else's

thoughts or ideas. The rest of World concerned him not at all, except for the necessary trade

through the stringers that brought him new toys and, occasionally, new books, which filled him

with new ideas. He knew, of course, of the seven gates to Hell, sealed long ago, and knew that

there were those who would open them once more and end World as he knew and liked it, but this

was a remote sort of threat that did not concern or worry him He knew, too, of the great Church

that ruled all twenty-eight Anchors, those places where no Flux existed and no powers worked,

but he thought the Church welcome to such areas. Whole nations without magic were Gyasiros'

own idea of what Hell must be.

Stringers had brought him word of a schism within that church, led by a priestess who was once

of Anchor but now a powerful wizard in Flux, but this, too, he tended to feel was no concern of

his. That had been far away and long ago, and what was it to him what theology ruled outside of

Yalah and was imposed on the common masses?

And when the Reformed Church had sent emissaries to Yalah, he had not even bothered to

listen to them. Although one had been a wizard of reasonable power and had been most insistent,

he had impatiently turned them both into dogs. Later, two more had come, both very strong

wizards, and he had been challenged somewhat. He found the challenge amusing, but on World,

where the power of a Fluxlord was measured by the amount of geography he or she could control

and stabilize, Gyasiros controlled one of the largest areas known.

In the end he'd changed the big man into a stately tree, and after that priestess or whatever she'd

been had been forced to dance naked in the streets and then lick his feet, he'd removed her power

of reason and freed her to live as an animal in his private forest.

But now, seeing the vast army besieging Yalah, he was beginning to feel annoyed.

This annoyance increased as the attack upon his shield commenced, an attack of such power

and ferocity as he'd never known. The energy reserves and concentration required to stand against

it caused the very ground to tremble and the reality of Yalah to shimmer and waver.

He began to get an awful headache.

Ultimately, he had to contract his shield boundaries a full ten kilometers to maintain a decent

level, but this actually increased the psychic attack, as there was now less area for the enemy to

concentrate upon. And as the shield withdrew, the armies advanced.

Not that he hadn't left all sorts of ugly surprises for them. The grass oozed acid that burned

through clothing and armor and into flesh, while the roads became ugly tar-pits that grabbed and

sucked down those who trod upon it, swallowing whole wagons. He knew that the attacking

wizards must divert some power to neutralize his traps, and he waited to open his counterattack

until he discerned a weakness in the attacker's will, but he sensed only a slight lessening of the

attack, and that for a very brief period, and he began to grow worried. He had been attacked many

times before by ambitious young wizards, some very powerful, who wanted to grab a ready-made

Fluxland and, in defeating him, create instant respect and recognition, but all had failed. This,

however, was different. These forces were seasoned troops, driven by some sense of mission, and

there were so many of them! He knew that his own population, vast as it was, lacked the skill and

training necessary to take them on in open battle. Oh, because he could command them, they

would fight to the death and take a heavy toll, but it didn't take great wisdom to see that an army

like this had faced that sort many times before—and was still here.

The headache grew far worse. He began to regret that he hadn't just sent those emissaries

packing. Now, with his record, he could hardly expect them to send someone else. Mentally he

cast about for his attackers, seeking the strongest wizard of the bunch. It was an easy task,

although all were quite powerful. This one stood out like a beacon on a dark night, and he seized

upon it. For the briefest moment he let down his guard for all save that one, and shot down its

energy flow a single concept he was certain would be understood.

"It was?"

Then it all went back up, and he resumed the fight, waiting to see if the challenge would be

taken. It was the simplest way out, but it would take some time after the wizard received and un-

derstood the message and invitation for word to get to the others. Now he could do nothing more

than draw as much energy as possible from the Flux and wait.

The waiting was about three hours, about what he'd expected. His headache was now

tremendous, but he was still holding on, after having to give up almost a quarter of Yalah.

Suddenly the attack on his shield ceased, and the relief was so great that this very cessation of

hostilities almost caused him to pass out. That he did not only confirmed his own self-image and

made him more confident. He was tired, true, but so were they, and so would be this one chief

wizard he would have to meet and, perhaps, take on, one-on-one.

He looked out and watched as grim-faced, battle-hardened troops heard a call and divided and

fell back in a mixture of awe and respect. The chief wizard, his true antagonist, was coming, as he

had hoped. Still, it was difficult to believe the wizard's appearance when finally it materialized.

She was a small, thin, boyish-looking woman. She looked almost dwarfed against the backdrop

of that great army. She had straight, stringy reddish-brown hair down to her waist, but wore no

makeup or jewelry and looked pale and thin, her face hard and worn, aged far beyond her years.

She wore only an old tattered robe that seemed two sizes too short for her and whose original

color could not really be determined. She was barefoot.

Although her appearance was startling, particularly for one of such power, he did not underesti-

mate her threat. Size, sex, age—none of that mattered in the Flux. He threw her a string—a weak

energy beam that remained stable from origin to destination—and she saw it and acknowledged it

with an offhanded nod to herself. Her body suddenly glowed, and then there was a bright flash

and a surge of energy along the string. In an instant she was no longer so far away, but in his

great hall, facing him.

Up close, she looked no different, only a bit older and more shopworn than he'd first thought.

He, on the other hand, presented a more than regal appearance to her, in his flowing white robes,

his golden, jewel-encrusted crown, and handsome, bearded face. He was at least two meters tall,

and his body was perfectly proportioned and solid muscle.

"I am Gyasiros Rex," he told her in a melodious baritone. "Who are you that come to my

domain, and for what reason?"

"I know who you are," she responded in a deep, throaty voice tinged with weariness and a trace

of sarcasm. "I saw all the statues of yourself. I am Sister Kasdi, of the Reformed Church. I sent

emissaries to you, not once but twice, in gestures of friendship. None of them ever returned. I

come this time myself, speaking the only language I suspect you understand or respect."

"I have no interest in your church, your mission, or your emissaries," he responded, a bit

irritated by her tone. He was not used to being talked to on anything like equal terms, let alone in

the contemptuous tones this woman was using. "I also do not threaten you or your objectives in

any way. I have what I want. I am content."

"You represent a potential threat to us that we must deal with. Many times in the past we have

come upon Fluxlands that seemed no threat, only to find that they were ruled or controlled by our

very enemies. We do not enforce conversation, so, if you had responded to our previous attempts,

all this might have been unnecessary. It is now necessary. You have power enough that you might

well be one of the Seven. That is sufficient reason to be here. If you are not, there will come a

time when outside forces will make you choose a side, and your actions indicate to us that you

would listen to the Seven over us. Your location is central to the routes we must take to the next

Anchor cluster. You are in the way."

"And I cannot choose to be neutral?"

"You could have chosen it once. You could have chosen it twice. You have created your own

situation. A neutral exists on trust. You have proven unworthy of trust. You have left yourself,

and us, no choice in the matter."

He looked down at her contemptuously. "And you are going to do this? You think yourself a

power superior to me? You, who use your power to dress in a rag and appear as ugly and worn as

a middle-aged farmer's wife might after decades of fighting the land and bearing a dozen young?"

"My power may be used only to further the cause of my church and my goddess. I have willed

it so."

"Then you are mad."

She sighed. "Aren't we all." It was not a question, but a statement of fact. "Still, better to

become one like me than to become a thing like you."

He drew himself to his full height and roared, "You will fall down and worship me! You will

kiss my feet and lick my holy ass!"

Anger rose within her at the thought of the probable fate of those who had come before. She

had nothing but contempt for such hedonistic, power-mad egomaniacs as this, and no more

compunction about dealing with them than she would when dealing with a poisonous snake.

"Shall we see?" she asked icily, and struck.

It was one thing to have to break down a shield, a great energy construct continually reinforced

from all the available energy within a Fluxland, but it was quite another face to face, with the

quarry in sight, with the energy equally available to both and in equal amounts. Whoever could

grab and direct the most of that vast yet finite energy would win any such contest.

Gyasiros felt as if every cell in his body had suddenly exploded and he screamed in mixed pain

and rage. Summoning every ounce of ego and will, he beat back the tremendous energy blast,

driving it from him and back towards its source. He drew in the energy around him, pushing it

with his mind out towards that blaze of yellow light that represented the energy of his attacker.

She parried by the same method, their force of wills creating a massive fireball seemingly sus-

pended between them in the great hall, a ball that blazed and grew as more and more energy was

poured into it by both sides. It did not remain still, however, creeping first one way, then the

other, in small spurts. It had taken only a minute for the energy to reach critical portions in a

literal sense. Whoever finally had that ball of fire forced onto their physical body could not stand

against it.

The Lord of Yalah was strong indeed, but so was she—the strongest he had ever encountered—

and he realized now the folly of issuing the challenge. She did not need to win, needed only to

stall for however long it took for her forces, taking advantage of the collapsing shield, to move

inwards towards the Fluxland's center, bringing with them wizards who at least would have had

some rest. Such was his power that he might well have held half his dominion with that shield,

but he could not maintain both shield and single combat.

The very realization of his mistake, and his self-acknowledgement of it, weakened his resolve.

The two were barely seven meters apart, yet the ball, which had been centered for so long, now

crept towards him until it was but two meters from him. And from the ball there came whispers,

thoughts, insinuations that he could not shut out.

"You are no god," the whispers said derisively, "nor is your power anything like absolute. You

are a mere man, a mortal man who can be killed by this woman and this thing creeping towards

you, creeping, creeping. . . . Even your godlike body is a fraud, as your life is a fraud, a show, a

thing not of majesty but of props and scenery, like theater. Even your power is illusion . . . ."

He fought back the whispered doubts, knowing their origin, but he could not shut out the

insults, the taunts, the claims, the—the blasphemy of it. And because he could not, he knew, in

some corner of his mind, that it must be true.

The ball crept closer, millimeter by millimeter.

Summoning every ounce of divine fury and will, he lashed back at it, and when it retreated, he

laughed aloud and his eyes blazed with the look of true madness, his confidence renewed as the

ball retreated almost to the center once again.

Suddenly the laughter died on his lips and he looked around, momentarily confused. It was hard

to breathe now. He opened his mouth to suck in air, but there seemed no air to come in. His

disorientation was brief, but it was enough.

Suddenly there was air again, and he drank it in, concentration wavering. The ball suddenly

rushed in upon him, enveloped him, held him in horrible pain. He had lost! But he couldn't lose!

He was Gyasiros Rex, God of Yalah, a creature of perfection whose power was omnipotent! But

if he could not lose, then what was this? Transcendence! The ball did not consume, but filled him

with power beyond imagining! He drank it in, more, more. . . . Not God of Yalah, but God of all

Creation! He was now supreme!

Kasdi broke with him and followed the string back to the lines, hoping it would be far enough.

Even now, still close to a hundred kilometers out, they saw the tremendous flash and, seconds

later, heard and felt the mighty roar of the explosion.

A shaken soldier near her turned, ashen-faced, and asked, "What in the name of all that is holy

was that?"

"Overload," she responded tiredly. "I gave him all the power of the battle and ninety percent of

the remainder. He took it in, unable to control himself any longer. There is only so much energy

that can be concentrated in one point. Beyond that, nothing can control it. When that point passed,

he could no longer hold it nor would it be held, so it ran from the point, dispersing in all

directions. It also dispersed him, of course."

"I just can't believe it could happen," he breathed.

"It was he who gave me the idea. I simply applied it literally. You see, all these powerful

Fluxlords are unstable."

2

DESTINY'S SAINT

It was hard being a saint, not only in being regarded as one by a large mass of people but also,

quite literally, being forced to be one. It was a self-inflicted wound that had been compounded

more and more over the years, but, as much as she disliked it, she believed more and more in the

necessity of it.

She sat in her office in the temple of Hope. It wasn't much of an office, really. An old wooden

chair whose finish was worn creaked with her every movement, although she was small and thin.

Her desk was a table in barely better repair, atop which sat a battered-looking old oil lamp,

various papers, and a pen and inkwell. Other than that the place was barren and quite small,

totally undecorated, its stone walls and floor more reminiscent of a monastic cell than the seat of

power of one of the most powerful people on World.

Although the temple and, indeed, the entire Fluxland of Hope was her creation, she spared little

of that power on herself. Although there were far less spartan offices and quarters, she disdained

them, and the only sop to her comfort was a small window behind her that allowed her to look out

on the temple grounds and the lands beyond.

She knew as well as anyone that all this was due less to a total act of faith than to the shock and

revulsion at seeing Matson fall in the battle for this place. Emotion was the trigger to the power of

the Flux, the raw motivator that multiplied a wizard's energy exponentially as the intensity of it

rose. Still, she felt, knew, that all of it had been a part of a divine plan and that she was the key

player anointed to carry that plan out.

The Church had been corrupted beyond any point of redemption, that she knew. It had turned

from its holy mission of salvation to one of repression, the alter-ego of the wizards of Flux. They

had perverted their entire faith into a massive and effective dictatorship and had held humanity in

the grip of their corrupt power for centuries, even rewriting Holy Scripture to support all their

moves. That had been one of her first and most important acts—the gathering of Scripture and all

other ancient and suppressed documents from the vaults of the Church and from sanctuaries in

Fluxlands, and then the appointment of a board of the finest scholars and translators to sort,

evaluate, and codify all of that material. It was a massive undertaking, and the Codex was still

years away from completion, but not from use.

Her mentor, Mervyn of Pericles, who was more than six centuries old and one of the powerful

Nine Who Guard, called what was being done a revolution, but it was true in only the most literal

sense. What she was doing was less revolution than restoration, putting humanity back on the

path from which it had been diverted.

To do this, she required a true and honest clergy, one immune to the sort of corruption the old

Church had fostered, and this had to be accomplished by magic. Ordination was more than a

commitment; it was the acceptance of spells binding one for life to those vows.

Because of this, she'd realized from the start that she had to set the example, had to be the saint,

for it was she who imposed those lesser but still binding restrictions on the vows. As the highest,

if she were not also the lowest, living a life that was far harsher than theirs, they could not be

expected to make the sacrifices and keep to them. Her life and actions had to make their own bur-

dens seem trivial by comparison, and it certainly did. Even Mervyn, who had taught her the one

unbreakable spell that could only be imposed freely on one's self, believed she had gone too far

and that the pressures of living such a life would eventually drive her mad. She had disagreed,

and over the seventeen years since those first vows she had in fact added to them whenever she

perceived a loophole.

The vow of poverty, of course, did not mean that the Church was poor. Far from it. It needed

the tithe to spread its word, support its temples, churches, and missions, its charity and its holy

works. The priestesses who did the work owned nothing, but had unlimited use of church

buildings, clothing, food, and the rest. They were not living like the rich and the wizard

monarchs, of course, but they were comfortable. She did not allow herself even that.

She quite literally had no possessions of any sort. No mementos of her past, no pictures or

souvenirs or keepsakes. She slept, in whatever random empty monastic cell she found, on a bed

of straw or, occasionally, on the stone floor. She had no aides or assistants; she cleaned out the

cell every morning, using common cleaning materials from the temple stores and scrubbing on

her hands and knees. She ate only the plainest of foods from the communal kitchens, along with

all the others, and she even washed her own dishes. Undergarments and shoes required a special

size and fit, so she had dispensed with them. She generally borrowed a comb and brush from

whoever was around, high or low, and returned them cleaned, and bathed either in the river or in

the communal showers used by the acolytes, the not-yet-priestesses who studied here. Her simple

robe was a worn-out cast-off of the temple which she washed each night. When it wore out, she

would hunt through the trash for another that would do. Even the desk, table, and lamp in the

office she had found in Anchor trash dumps and repaired herself as much as she could for use.

She allowed no one to wait on her, and she accepted no charity, although she would accept an

offer of dinner or such in Anchor or Flux if it were truly offered in friendship and without

expectations. She did not smoke, drink, or even swear—the spell prevented it. And her chastity

was absolute, so much so that even simple self-stimulation was beyond her. This didn't mean she

didn't feel the need for such things—she often did, particularly in the early days—but she had

made it impossible for her to violate her way of life. By now, though, she hardly gave any of it a

thought. It was the way it was, the way it had been for most of her adult life, and the way it would

always be.

She had not just done this to create an example and remove all temptation from her, though. In

a very real sense, it liberated her from all the pressures of daily life and from its temptations as

well. She desired nothing she did not already have, save an end to these wars and the total

reformation of the Church; she had nothing at all that anyone else might want except, perhaps, her

wizard's power, which could not be transferred in any event. She knew that, while many might

covet high Church positions, none wanted her job—not with the living conditions that came with

it.

She took no part in the day-to-day affairs of running the Temple or the Church as a whole. She

knew she was not temperamentally suited to be the administrative type. Her jobs, her only jobs,

were spreading the reformation throughout World and purifying and restoring the faith and

keeping it pure.

The only time she used her powers for her own gain, other than to ward off starvation or

desperate thirst, was when she went out alone across the void to Anchor. There was an inevitable

tendency for people to mistake the agent for the boss; she was virtually worshipped by many as

some sort of deity herself, a fact that made her uncomfortable, but which had proved impossible

to stamp out completely. To go out alone, particularly on personal business, she required a

disguise, and transformed herself, for that purpose only, into the guise of a low-ranking priestess

of far different appearance. It allowed her a measure of temporary anonymity, although she was

still bound to her lifestyle.

For she did have one thing that might be used against her if known. She had a daughter, it was

true, and she had done all she could to keep that fact and her daughter's identity a deep secret. She

had once considered a vow of truthfulness to match her vow of honesty, but had rejected it. That

much corruption she had to allow, for a good cause. The official story was that her child had been

stillborn. She could hardly hide the signs in those early days, and although she'd used her powers

to eliminate the stretchmarks and other signs, it was known she'd borne a child in Anchor.

Had the child been born in Flux, it would have been a painless and effortless birth, though also

one that could hardly be a seat of deception. Ironically, the lying powers of Flux would not permit

an imperfect birth to a wizard; only in Anchor could the child "die" as it had to. In fact, the child

had been born perfectly in any event, and those involved had voluntarily submitted to changes in

their memory to conform to the official version, those changes made by Mervyn in Flux. Only

four people knew that the child lived and who she was: Kasdi, of course, and her cousin Cloise,

who had taken the child and raised it as her own in Anchor Logh, as well as the wizard Mervyn

and the Sister General of Logh, Tamara, her oldest and closest friend.

The child had been named Spirit—it was her one conceit, and seemed inevitable. She knew that

she was adopted, of course—the records of Anchor were more likely to trip them up than hide

them in their scheme if they had pretended otherwise— but believed that her parents had died in

the conflicts raging back at that time. Nor did Spirit look anything like either Kasdi or Matson;

that had been a part of it, too, as any enemy might well look at Kasdi's native land and her large

family there in its search for things to use against her.

Spirit had grown into a young woman now, and it was a shock to see her these days. Olive-

skinned and curvaceous, well-built as Kasdi herself never was, with a beautiful face and long,

black hair and huge, soft brown eyes, she was the heartthrob of every teen-age boy in Anchor

Logh.

Sister Kasdi ached every time she thought of Spirit, which was all the time she wasn't preoccu-

pied with matters of duty. She was proud of her daughter in every way, for Spirit was also excep-

tionally bright and at least shared her real mother's love for animals and nature, but there was

much guilt there, too. Although Spirit had been well brought up in an atmosphere and

surroundings not unlike her mother's, the girl had been raised by others. Although she had kept

close track of her daughter's progress, she'd really had no input into anything not genetic in her

only child's upbringing. Oh, she'd visited Spirit when she could, under the guise of a priestess

who was a cousin of her late mother's, but that was about it.

She was lost in such thought when she suddenly became aware of a throat clearing and snapped

out of it for a while. Sister Karla, the administrative priestess for the level, stood there looking

apologetic. "Sorry I must disturb you, Sister, but the wizard Mervyn is here to see you."

Kasdi brightened a bit. "Send him in! And don't hesitate to disturb me. It is not good when I

think too much."

The priestess frowned a moment in puzzlement, then turned and walked back out the door. A

moment later Mervyn entered, stopped, and looked around. He had the look of a very old man

with flowing white hair and beard and a floor-length robe of cream-colored silk embroidered with

gold trim. It was not a church robe, of course—only women could be priestesses—but one more

in keeping with the image he liked to project. Only his bright, piercing eyes that seemed to look

everywhere at once revealed the strength hidden in that baggy robe and those ancient features.

"Hmph! No furniture for guests yet, I see." He made a quick pass with his hand and then sat—

in a comfortable, padded chair which simply appeared behind him. He studied her face for a

moment. "You look lousy," he told her.

She chuckled. "Always the soul of tact, aren't you?"

"After six hundred and forty-seven years I have earned the right not to have to play silly social

games. You're—what?—thirty-six, and you look half as old as I do. Your eyes and bearing look

even older, and that's going some."

"It hasn't been a very easy life, as you well know. That Yalah business a week ago took a lot

out of me, too. I slept for three days after that, and since that time I've been happy just living

simply and routinely here."

He rose slightly and looked on the table at the paper in front of her. It was a map of World, a

very simple map with a few notations written in by Kasdi. It was a record of progress and

achievement unprecedented in history, but he suspected that this record wasn't what she saw in

that map. Instead, it represented seventeen years of hard work and sacrifice on her part. The map

was her autobiography.

The map showed the seven "clusters" of Anchors, four to a group, or cluster, each equidistant

from a Hellgate in the center of the square they formed. They were quite symmetrically spaced

around the perimeter of the planet, a fact that only reinforced the logic of a divine plan. A full

four clusters were now under the Reformed Church, more than half the planet, with the Fluxlands

between, inside, or on the stringer routes through the void that connected them, all either under

the control of her partisans or in truce with them. There were still many bizarre lands there, and

many mad rulers like the late, unlamented Gyasiros, but all had chosen not to challenge her power

but to accommodate it.

The rest had fallen through a combination of arms and sorcery, as had Gyasiros. They had been

tough at the start, with much bloodshed and wizards' contests, but there were few such these days.

The word was getting around, and all save the maddest of egomaniacs found some room in their

demented psyches for a compromise between the Church's wishes and their own egos. Not that

the old Church and the old order had been a pushover, but not since the Battle of Balacyn, four-

teen years earlier, when armies of more than a million faced off in Flux, along with some of the

most powerful living wizards known—on both sides—had they tried a major offensive. Still, the

next cluster would be as well-defended as any in the past, and both sides still lost bitter and

bloody battles.

In fact, although much of Flux was getting easier, the Anchors were becoming harder and

harder, as the opposition had plenty of time to prepare and had learned so much about its foes.

Now only stringers crossed the line between old and new, and only with difficulty and much

suspicion.

"I worry about how much longer we have to go," she told him wearily. "How many more years,

how many more lives?"

"I'd worry about what happens when it's done," he responded.

"Huh?"

"We're the founders of a new world here. Science once again is flowering in Anchor, and a

freed people are building new institutions, new ways, that we never dreamed of. Eventually there

will be greatness here again—and you will have shut yourself off from ever being a part of it. In

the name of moving this world forward, you've pushed yourself backward to the most primitive

sort of life. Have you ever thought of that?"

"No," she answered truthfully. "There's no way to do what must be done for this new world you

speak of if I think of my own future. The next problem, the next march, the next Yalah, the next

threat to what we have already built—those occupy my mind." She sighed. "I suppose I shall

retire when it's over. Walk World from end to end, pole to pole, seeing all that there is to see.

Perhaps teach or preach or both. I don't know. It's so far off."

"Maybe, maybe not."

"But that wasn't what you came all this way to talk about, and I know it. Now—what's the real

reason for all this?"

"The greater evil is on the move once more. I think at least the first part of the move will be in

your direction."

Her eyebrows rose. "You mean the Seven? I thought we must have weakened them

enormously; it's been so long since they tried anything."

He sighed. "They are not at all weakened, nor is your statement correct. They are, in most

cases, very much in the background. Only rarely does one like a Haldayne draw attention to

himself, and then only when it's part of the plan. Just who do you think we've been fighting all

these years?"

"Why, the old Church, of course!"

"And who exactly is the old Church? Doesn't corruption on such a scale show us something

right there? I have just recently come into some information that suggests that Her Perfect

Highness, the Queen of Heaven, might in fact be Gifford Haldayne's older sister."

That startled her. "What! I have fought them a long time, I know, but I never thought—"

"Yes, indeed," he interrupted. "Who would? This is not to say that the church is, as an entity, a

direct and knowing agent of the Seven. Proof of that would be sufficient to win you the rest of

World without lifting a finger. But the corruption begins at the very top. How do you suppose

they finally discovered the gate entrances inside the temples, buried under the very foundations?

They poked and probed and experimented until it was discovered—having access to temples."

"But—this is monstrous!"

"Indeed. However, up to now it's worked to our advantage. The Seven now control three of the

gates through their subtle control of the church. They are very busy making certain they lose no

more of those gates. Had we not discovered them shortly after they discovered the temple

entrances and denied them access to at least one, they might have fulfilled their plan without us

even realizing it was so until the hordes of Hell overran us. That's what your Soul Rider was

rushing to Anchor Logh to prevent, and when it did, it rushed to some other emergency. Since

then, they've been very busy just trying to hold onto what they have, and with not much success.

If you spent years fighting off an attacker and still knew you were losing, would you keep on

doing the same thing?"

She considered it. "No. Of course not. I would have acted long before this, in fact."

He nodded. "I think the Queen of Heaven is the boss—or was, anyway. She kept them in line

because the church was the seat of her power, and she threw everything into trying to keep it.

Now, however, my agents inform me that the others have rebelled, citing her failures, and that she

has been forced to go along. There was allegedly a summit meeting of all Seven, the first such

known to me. At that meeting all the restraints came off. Our friend the Queen of Heaven will

continue to defend in her old ways, perhaps assisted by others, but there will now be a division of

forces and a new direction. The word in Flux is that they want to tackle you first, before this

grand new plan is put into operation."

"You mean, call me out and face me down? I'd almost welcome that, even three or four to one."

"Don't take it lightly. They are more powerful than any other wizards known, except for

yourself. It is my firm conviction that one or perhaps several of them are at least your equal.

However, calling you out is simply not their way. It would bring the Nine in a flash, and they

know it. They are not ready to face down all of us. They are infinitely patient, preferring to

minimize risks to themselves and suffer a thousand defeats if they gain the final victory. Still,

they are diabolically clever and you must be on guard." He paused a moment. "I fear that your

one soft spot in your armor may be in peril."

She felt a shock go through her. "But—how could they know? And if they did, why haven't

they acted before now?"

He shrugged. "I don't know if they know or not, but as to the timing—perhaps, like the

Hellgate, they just found out. As I said, they are a patient lot. And that brings up a rather chilling

question. What would you do if they got her and offered a trade?"

She shivered at the idea. "I don't know. I honestly don't."

"You would not be permitted to do so," he warned her. "The Nine would prevent you, no matter

what. You are a symbol that, right now, we cannot do without."

"But the Seven know that, too. Isn't that some form of insurance?"

He shook his head sadly. "Perhaps. But they are devious in the extreme. They have failed

militarily. To gain the seven gates, they must infiltrate and, if possible, corrupt the Reformed

Church. To do that, they must remove—or corrupt—you." He sighed. "We could put more of a

watch on her, of course, but that alone might tip them off if they don't yet have the exact one. Or

we could bring her here, to Hope. It is the best-guarded, safest place anyone could be."

She shook her head negatively at that. "What sort of life would it be for her here? She's shown

no inclination towards the priesthood and much for the boys. There'd be no joy for her in Hope."

"You didn't have much inclination for the priesthood yourself at her age, and look what

happened to you. But, let that pass for now. There is always Pericles, which is also as safe as they

come."

"But just taking her there would point a finger at her. Then they would know, and, as you said,

they are patient. She would be a prisoner there for as long as I was a threat to the Seven. That

might be decades."

"Then we leave things as they are," the wizard said flatly. "I don't like it, but there it is. At least

you should do one thing for her—you should tell her her true origins and parentage."

The idea frightened her. "Uh—no. Not yet. She would never understand. She would never

forgive me!"

"If she is at risk, she must know it and know the reason why. She must be prepared to defend

herself. If we do not remove her from harm's way, then we must give her every chance. We can't

keep diverting her, nailing her into Anchor Logh. She's inquisitive, just like her mother. She

wants to see the whole of World. I think it is time. You have inflicted so much sacrifice and

injury upon yourself—now it is time to do it once more, this time for the sake of another."

She sighed. "I'll meditate and pray on it. That's all I'll promise right now."

"Don't think or meditate or pray too long," he warned her. "Evil is on the march once more, and

the more they are set back, the more determined, devious, and dangerous they become."

Tomorrow would be a Service of Ordination at the Temple of Hope. When she was there, Kasdi

liked to preside over it herself, although there were by now many other powerful wizard-

priestesses capable of administering the rites. It was something she liked to do, a sort of

affirmation of the rightness of her cause and the future of World to see those bright, young faces

eagerly accept the vows without coercion.

Once young women were almost forced into the priesthood when they possessed some talent or

ability the church needed. They were immediately ordained so they could never quit, then

underwent three years of rigid indoctrination—brainwashing, she'd heard it called. She had

changed all that when she'd abolished the barbaric and terrible Paring Rite that had cast her out of

Anchor into Flux. Now the Flux, at least in her areas, was not such a terrible or threatening place,

and population controls were managed quite easily by voluntary shifts. Those who discovered

that they had some Flux power—either false, in which all their spells were illusion, or true, in

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

SOULRIDERII:EMPIRESOFFLUXANDANCHORJackL.ChalkerCopyright©1984byJackL.ChalkerISBN:0-812-53-277-5e-bookver.1.0ForSomtowSucharitkulaspectacleofunmitigatedhorrorwithadashofBakti1RECALCITRANTGODSGodsdonotnormallyexpecttolookoutthewindowsoftheirpalatialheavensandseeanenemyarmyadvancing.GyasirosRex,LordofY...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:134 页

大小:1.15MB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-04

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394