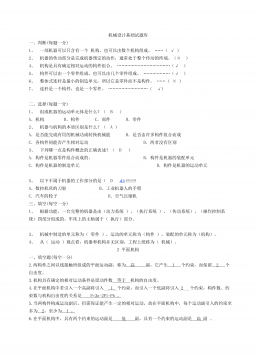

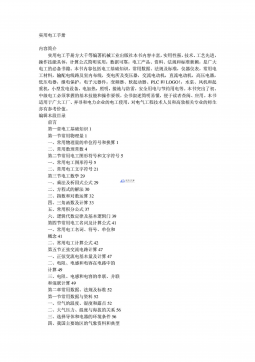

Dataset Name Langs. Domain Topics Date of Data Engagements Size Labels

LIAR (Wang,2017) En Statements MISC 2007-2016 None 12.8k Annotated

FakeNewsNet (Shu et al.,2020) En News, tweets MISC n/a None 23.1k, 1.9m Query

CoAID (Cui and Lee,2020) En News, tweets C19 2019-2020 Reply 4.2k, 160k Query

COVIDLies (Hossain et al.,2020b) En Tweets C19 2020 None 6.7k Annotated

CMU-MisCOV19 (Memon and Carley,2020) En Tweets C19 2020 None 4.5k Annotated

MM-COVID (Li et al.,2020) 6 langs. Tweets C19 n/a Reply, retweet 105.3k Query

VaccineLies (Weinzierl and Harabagiu,2022) En Tweets C19, HPV 2019-2021 None 14.6k Annotated

MuMin (Nielsen and McConville,2022) 41 langs. Tweets MISC n/a Reply, retweet 21.5m Query

MR2 (Hu et al.,2023) En, Zh Tweets, Weibo MISC 2017-2022 Reply, retweet 14.7k Annotated

MiDe22 (this study) En, Tr Tweets RUW, C19, IMM, MISC 2020-2022 Reply, retweet, like, quote 10.3k Annotated

Table 1: Related misinformation studies. RUW stands for Russia-Ukraine War, C19 for COVID-19,

IMM for Immigration and Refugees, HPV for Human Papilloma Virus, and MISC for Miscellaneous. The

last column shows if tweets are annotated by humans, or labeled by the output of queries to Twitter API.

Size is given in terms of number of tweets.

2. Related Work

In this section, we provide a brief review of the

existing literature and explore the methods used for

the analysis and detection of misinformation, the

available datasets for research purposes, and the

various interventions implemented to combat the

spread of misinformation.

2.1. Misinformation Analysis

Misinformation analysis is the process of identi-

fying, evaluating, and understanding the spread

and impact of false, misleading, or inaccurate in-

formation. Misinformation modeling covers tempo-

ral and patterns of information diffusion to analyze

spread (Shin et al.,2018;Rosenfeld et al.,2020),

and also analysis of misinformation spreads during

important events such as the 2016 U.S. Election

(Grinberg et al.,2019), the COVID-19 Pandemic

(Ferrara et al.,2020), and the 2020 BLM Movement

(Toraman et al.,2022a).

2.2. Misinformation Detection

Misinformation detection is a challenging task when

the dynamics subject to misinformation spread are

considered. The task is also studied as fake news

detection (Zhou and Zafarani,2020), rumor detec-

tion (Zubiaga et al.,2018), and fact/claim verifica-

tion (Bekoulis et al.,2021;Guo et al.,2022).

There are two important aspects of misinforma-

tion detection. First, the task mostly depends on

supervised learning with a labeled dataset. Second,

existing studies rely on different feature types for au-

tomated misinformation detection (Wu et al.,2016).

Text contents are represented in a vector or embed-

ding space by natural language processing (Os-

hikawa et al.,2020) and the task is formulated as

classification or regression mostly solved by deep

learning models (Islam et al.,2020a). The features

extracted from user profiles can be used to detect

the spreaders (Lee et al.,2011). Besides contents,

there are efforts to extract features from the network

structure such as network diffusion models (Kwon

and Cha,2014;Shu et al.,2019a) and graph neu-

ral networks (Mehta et al.,2022). Lastly, external

knowledge sources (Shi and Weninger,2016;Tora-

man et al.,2022b) and the social context among

publishers, news, and users (Shu et al.,2019b) can

be integrated to the learning phase.

Rather than identifying the content with misin-

formation, there are efforts to detect the user ac-

counts that would spread undesirable content such

as spamming and misinformation. Social honeypot

(Lee et al.,2011) is a method to identify such users

by attracting them to engage with a fake account,

called honeypot. There are also bots producing

computer-generated content to promote misinfor-

mation (Himelein-Wachowiak et al.,2021).

2.3. Misinformation Datasets

There are several efforts in the literature to con-

struct a dataset for misinformation detection. The

LIAR dataset (Wang,2017) includes short state-

ments from different backgrounds, annotated by

PolitiFact API. News and related tweets for fact-

checked events are composed in a dataset in (Shu

et al.,2020). Recently, global events and their

repercussions in social media lead to the emer-

gence of new misinformation datasets. For in-

stance, Memon and Carley (2020) annotate tweets

according to misinformation categories such as

fake treatments for COVID-19. In (Li et al.,2020),

news sources are investigated for fake news in

different languages. Hossain et al. (2020b) re-

trieve common misconceptions about COVID-19,

and label tweets according to their stances against

misconceptions. Weinzierl and Harabagiu (2022)

compose the vaccine version of the same dataset.

Other datasets include COVID-19 healthcare misin-

formation (Cui and Lee,2020), and large-scale mul-

timodal misinformation (Nielsen and McConville,

2022). (Hu et al.,2023) curate annotated multi-

modal social media dataset for two widely-spoken

languages (English and Chinese), providing reply

and retweet engagements. Lastly, there are very

limited datasets for low-resource languages (Hos-

sain et al.,2020a;Lucas et al.,2022) but do not

exist for Turkish.

2024-11-15 27

2024-11-15 27

2024-11-15 16

2024-11-15 16

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 6

2025-04-07 6

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394