Philip Jose Farmer - Lord Of The Trees and The Mad Goblin

EVENTHEAPE-MANHIMSELFHASHISPRICE...Thirtythousandormoreyearsago,someOldStoneAgepeoplesdiscoveredsomethingthatgavethemanextremelyextendedyouth.Italsomadethemimmunetoanydiseaseorbreakdownofthecells.Ofcoursetheycouldfalldownandbreaktheirnecksorslittheirthroatsorgetclubbedtodeath.Butifchanceworkedwellfo...

相关推荐

-

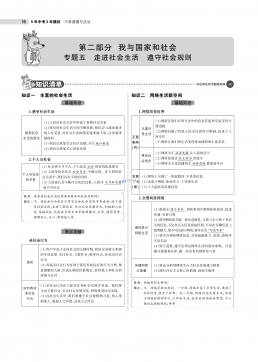

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包05专题五 走进社会生活 遵守社会规则VIP免费

2024-11-21 7

2024-11-21 7 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包05专题五 走进社会生活 遵守社会规则VIP免费

2024-11-21 10

2024-11-21 10 -

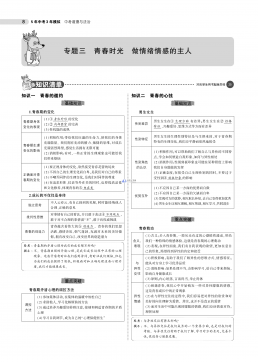

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包03专题三 青春时光 做情绪情感的主人VIP免费

2024-11-21 5

2024-11-21 5 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包03专题三 青春时光 做情绪情感的主人VIP免费

2024-11-21 7

2024-11-21 7 -

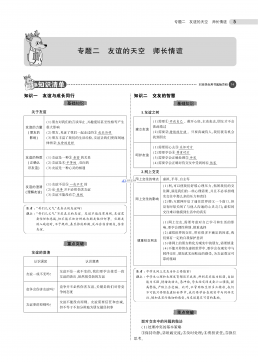

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包02专题二 友谊的天空 师长情谊VIP免费

2024-11-21 8

2024-11-21 8 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包02专题二 友谊的天空 师长情谊VIP免费

2024-11-21 7

2024-11-21 7 -

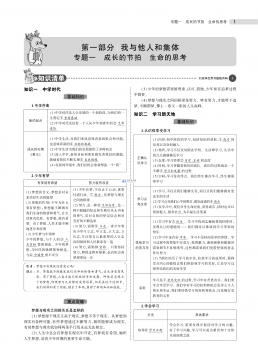

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包01专题一 成长的节拍 生命的思考VIP免费

2024-11-21 5

2024-11-21 5 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包01专题一 成长的节拍 生命的思考VIP免费

2024-11-21 7

2024-11-21 7 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包《53中考》全国道德与法治资料包VIP免费

2024-11-21 9

2024-11-21 9 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包07专题七 坚持宪法至上 崇尚法治精神VIP免费

2024-11-21 6

2024-11-21 6

作者详情

-

VP-STO Via-point-based Stochastic Trajectory Optimization for Reactive Robot Behavior Julius Jankowski12 Lara Bruderm uller3 Nick Hawes3and Sylvain Calinon125.9 玖币0人下载

-

WA VEFIT AN ITERATIVE AND NON-AUTOREGRESSIVE NEURAL VOCODER BASED ON FIXED-POINT ITERATION Yuma Koizumi1 Kohei Yatabe2 Heiga Zen1 Michiel Bacchiani15.9 玖币0人下载

相关内容

-

精品解析:2022年山东省济南市中考历史真题(原卷版)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-08-19

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

2014年福建省龙岩市中考数学试卷(含解析版)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-08-19

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

-

2014年福建省福州市中考数学试卷(含解析版)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-08-19

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

-

2014年北京市中考数学试卷(含解析版)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-08-19

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

-

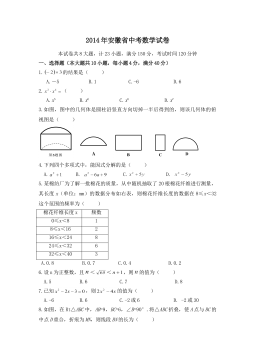

2014年安徽省中考数学试卷(含解析版)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-08-19

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394