Robert Silverberg - Tower of Glass

ThisebookispublishedbyFictionwisePublicationswww.fictionwise.comExcellenceinEbooksVisitwww.fictionwise.comtofindmoretitlesbythisandothertopauthorsinScienceFiction,Fantasy,Horror,Mystery,andothergenres.Copyright©1970byRobertSilverbergFictionwisewww.fictionwise.comCopyright©1970byRobertSilverbergISBN1...

相关推荐

-

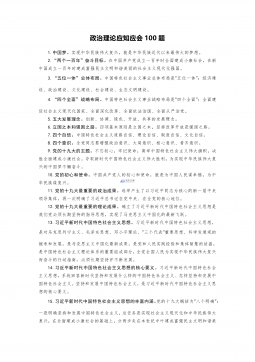

政治理论应知应会 100 题VIP免费

2024-12-12 357

2024-12-12 357 -

2025年中央机关及其直属机构录用公务员考试 行政职业能力测验(地市级)(经典模考卷三)解析VIP免费

2024-12-12 46

2024-12-12 46 -

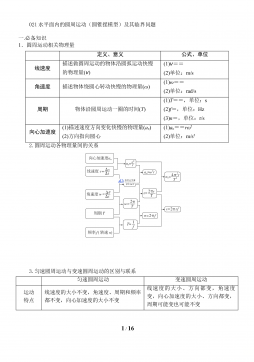

021水平面内的圆周运动(圆锥摆模型)及其临界问题 精讲精练-2022届高三物理一轮复习疑难突破微专题VIP免费

2025-01-04 41

2025-01-04 41 -

21学位英语:从句考点真题VIP免费

2025-04-08 4

2025-04-08 4 -

19学位英语:2010年阅读理解分析VIP免费

2025-04-08 4

2025-04-08 4 -

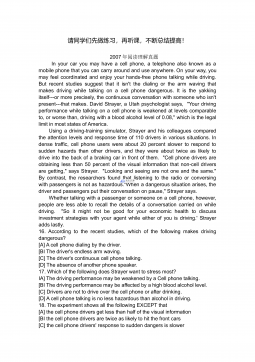

[16] 学位英语:2007年阅读理解分析VIP免费

2025-04-08 4

2025-04-08 4 -

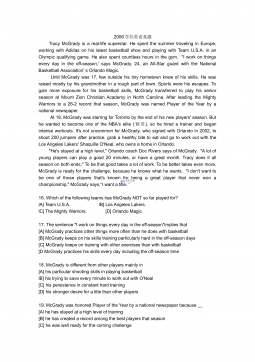

[15] 学位英语:2006年阅读理解分析VIP免费

2025-04-08 10

2025-04-08 10 -

[14] 学位英语:2005年阅读理解分析VIP免费

2025-04-08 12

2025-04-08 12 -

[13] 学位英语:2004年阅读理解分析VIP免费

2025-04-08 8

2025-04-08 8 -

[10] 学位英语:长难句拆分(二)VIP免费

2025-04-08 10

2025-04-08 10

作者详情

-

VP-STO Via-point-based Stochastic Trajectory Optimization for Reactive Robot Behavior Julius Jankowski12 Lara Bruderm uller3 Nick Hawes3and Sylvain Calinon125.9 玖币0人下载

-

WA VEFIT AN ITERATIVE AND NON-AUTOREGRESSIVE NEURAL VOCODER BASED ON FIXED-POINT ITERATION Yuma Koizumi1 Kohei Yatabe2 Heiga Zen1 Michiel Bacchiani15.9 玖币0人下载

相关内容

-

[16] 学位英语:2007年阅读理解分析

分类:高等教育

时间:2025-04-08

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:5.9 玖币

-

[15] 学位英语:2006年阅读理解分析

分类:高等教育

时间:2025-04-08

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:5.9 玖币

-

[14] 学位英语:2005年阅读理解分析

分类:高等教育

时间:2025-04-08

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:5.9 玖币

-

[13] 学位英语:2004年阅读理解分析

分类:高等教育

时间:2025-04-08

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:5.9 玖币

-

[10] 学位英语:长难句拆分(二)

分类:高等教育

时间:2025-04-08

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:5.9 玖币

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394