Lin Carter - Callisto 6 - Lankar Of Callisto

Jandar6:LankarofCallistoByLinCarterChapter1THECITYINTHEJUNGLEItwasearlyafternoonwhenwelandedattheSiemReapairportjustnorthofthecapitalcity.Wehadtowaitininterminablelinestocollectourluggageandtogothroughpassportexaminationandcustomsinspection.Eventuallyweemergedunderadarkeningskytobegreetedbygrinningp...

相关推荐

-

【词汇变形总汇】2025高考词汇变形总汇 - 教师版VIP免费

2024-12-06 4

2024-12-06 4 -

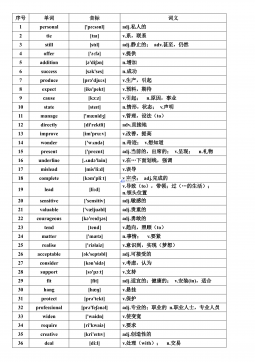

【超简37页】新课标高考英语考纲3500词汇VIP免费

2024-12-06 11

2024-12-06 11 -

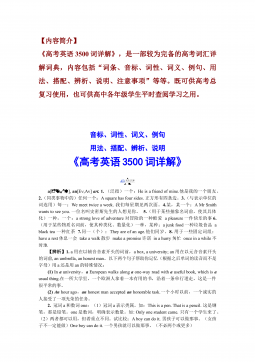

《高考英语3500词详解》(WORD版)VIP免费

2024-12-06 29

2024-12-06 29 -

《高考英语3500词详解》VIP免费

2024-12-06 26

2024-12-06 26 -

高中英语-[教师版]80天通关高考3500词汇VIP免费

2024-12-06 29

2024-12-06 29 -

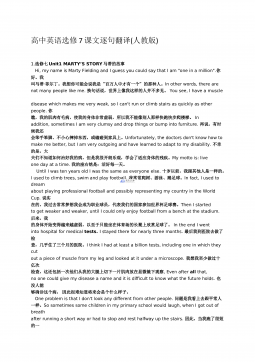

高中人教选修7课文逐句翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 11

2024-12-06 11 -

高中人教选修7课文原文及翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 35

2024-12-06 35 -

高中人教必修4课文逐句翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 12

2024-12-06 12 -

高中人教必修4课文原文及翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 40

2024-12-06 40 -

高考英语核心高频688词汇VIP免费

2024-12-06 29

2024-12-06 29

作者详情

相关内容

-

安徽省部分地市2024-2025学年高一下学期开学考试生物学试题(含答案)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-12-03

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

安徽省部分地市2024-2025学年高一下学期开学考试地理试题(含答案)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-12-03

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

安徽省部分名校2025届高三12月联考化学试题

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-12-03

标签:无

格式:PDF

价格:10 玖币

-

安徽省部分地市2024-2025学年高一下学期开学考试 化学 PDF版含解析

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-12-03

标签:无

格式:PDF

价格:10 玖币

-

安徽省部分地市2024-2025学年高一下学期开学考试 化学 PDF版含解析

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-12-03

标签:无

格式:PDF

价格:10 玖币

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394