spirals and woven lacings, amarelo buds and leaves in oval car-touches, took concentration and more

patience than I thought I had until I started working on it. I’d put together frames before this one, trying

one thing and another, different shapes, different woods, you get the idea; I wanted to make the sound as

perfect as the shape. Far as I could tell. My ear’s not so bad, but my fingers are all thumbs. The last one

before this had a warm rich tone, I was quite pleased with it. When Shadith sent word she was coming, I

got it out with a couple more and tuned them, I wanted to know what she thought.

Back yard’s a comfortable place. I spend a lot of time here, working, reading, contemplating my

navel, whatever. Got a plank fence around it to keep the vermin out. Flowering thornbushes grow in

stripbeds against the planks. A sight to see, they are, come spring when every cane is-thick with bloom.

No roof, but there’s a deflecter field for when it rains, keeps the wet out without ruining the skyview,

which can be spectacular during summer storms. One of them was blowing up the day I’m talking about,

clouds were gathering over Stormbringer’s peak, they’d be down on us in an hour or so. I’ve got the

ground under my worktable paved with roughcut slabs of slate. Some of them are cracked; griza grass

grows in these cracks and between the slabs, that’s a native grass, dusty looking gray-green, puts out

seedheads in the spring, not the fall, they stand up over the blades like minute denuded umbrella ribs.

Beyond the stone there’s mute clover, griza doesn’t have a chance against it. There are stacks of wood

sitting around, some roughcut planks, some stripped logs. I’ve got a largish workshed in the south corner,

the roof is mostly skylight; I store my tools in there but don’t work inside except in winter when it’s too

cold to sit in the garden. Or when I need to use the lathe or one of the saws. There are two viuvars (like

short fat willows) growing beside the shed and a tendrij in the north corner. The tendrij was here on my

mountainside before I built my house. The trunk’s a pewter column a hundred meters tall and thirty

around; branches start about fifty meters up, black spikes spiraling around the bole; the leaves if you can

call them that look like ten meter strips of gray-green and blue-green cellophane. When the storm winds

blow them straight out, they roar loud enough to deafen you; on lazy warm spring days like this one, they

shimmer and whisper and throw patches of shift-ing greens and blues in place of shadow.

My worktable is a built-up slab of congel wood. Tough, that wood, takes a molecular edge to work

it, but it lasts forever; a benefit to living on Telffer, you pay in blood for congel offworld. Mottled medium

brown with patches of gold like a pale tortoiseshell.

Pretty stuff, which is a good thing because it won’t take stain any way you try it and even paint peels

off, something about the oil, they say. I had the gouges I was using laid out on a patch of leather close to

hand, the tool kit beside it, the frame I was working on set in padded clamps, the finished harps down at

the far end waiting for Shadith to try them.

Butterflies flittered about, lighting on the thornflowers, feeding on their pollen; a sight to add pleasure

to the day, but it meant I’d got worms in the wood and I was going to have to fumigate the yard. There

were quilos squealing in the viuvars. Quilos are furry mats with skinny black legs, six of them, and deft

little black fingers on their paws. Never been able to find any sign of eyes, ears or nose on them, though

they’re fine gliders and can skitter about on the ground like drops of water on a greased griddle. They

drive the cats crazy, how can you prowl downwind of a thing that’s got no nose or chase something that

can switch direc-tion without caring which end is front? I had five cats last time I counted and they’re all

neutered, so that should be that, but none of them are black and two days ago I saw this black body

creeping low to the ground, going after a quilo who was chewing on a beetle it picked off a thornbush,

it’s why I tolerate a few of the things about, they keep the bug population down. I threw a chunk of

wood at the cat and it streaked off. A young black tom. Pels says he thinks there’s something mystical

about black toms, there’s never an assemblage of cats without one of them show-ing up, he says he’s

convinced they’re born out of the collective unconscious of cats, structures of unbridled libido created to

assuage cat lust. He may be right.

Pels kurk-Orso. Let’s see. He’s my com off and aux pilot. He’s got a thing with plants and keeps my

Slancy green; he’s heavyworld born and bred, Mevvyaurang; not many have heard of it, Aurrangers

aren’t much for company or traveling. 2.85 g. Where they have three sexes. Sperm carrier (Rau), seed

carrier (Arra), womb-nurse (Maung). He’s Rau. Hmm. There’s a heavy burden he has to bear. Drives

him into craziness some-times. Females of every sentient species I’ve come across, even the reptilids,

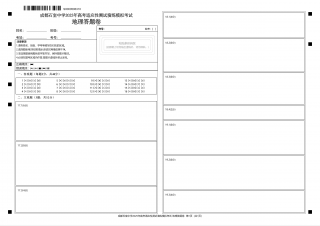

2024-12-01 6

2024-12-01 6

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 8

2024-12-01 8

2024-12-01 30

2024-12-01 30

2024-12-01 23

2024-12-01 23

2024-12-01 17

2024-12-01 17

2024-12-01 9

2024-12-01 9

2024-12-01 13

2024-12-01 13

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394