Dean Ing - Silent Thunder

>> DEANING -SILENT-THUNDER OtherbooksbyDeanIngSingleCombatWildCountryBloodofEaglesTheBigLiftersTheRansomofBlackStealthOne Thisisaworkoffiction.Allthecharactersandeventsportrayedinthisbookarefictitious,andanyresemblancetorealpeopleoreventsispurelycoincidental.SILENTTHUNDERCopyright1991byDeanIngAl...

相关推荐

-

【词汇变形总汇】2025高考词汇变形总汇 - 教师版VIP免费

2024-12-06 5

2024-12-06 5 -

【超简37页】新课标高考英语考纲3500词汇VIP免费

2024-12-06 16

2024-12-06 16 -

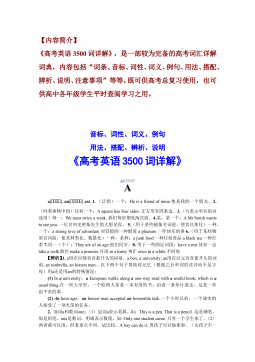

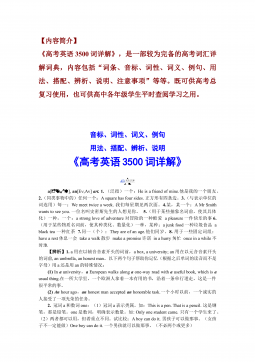

《高考英语3500词详解》(WORD版)VIP免费

2024-12-06 30

2024-12-06 30 -

《高考英语3500词详解》VIP免费

2024-12-06 27

2024-12-06 27 -

高中英语-[教师版]80天通关高考3500词汇VIP免费

2024-12-06 33

2024-12-06 33 -

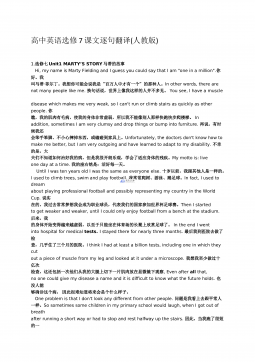

高中人教选修7课文逐句翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 14

2024-12-06 14 -

高中人教选修7课文原文及翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 38

2024-12-06 38 -

高中人教必修4课文逐句翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 23

2024-12-06 23 -

高中人教必修4课文原文及翻译VIP免费

2024-12-06 57

2024-12-06 57 -

高考英语核心高频688词汇VIP免费

2024-12-06 33

2024-12-06 33

作者详情

相关内容

-

江苏省南通市通州区、如东县2025届高三上学期期中联考英语

分类:中学教育

时间:2026-01-20

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

江苏省南通市名校联盟2024—2025学年高三模拟演练语文

分类:中学教育

时间:2026-01-20

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

江苏省南通市海安市2024-2025学年高三上学期开学考试语文试题(无答案)

分类:中学教育

时间:2026-01-20

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

江苏省南京市、盐城市2025届高三上学期第一次模拟考试语文试题(含答案)

分类:中学教育

时间:2026-01-20

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

江苏省南京师范大学附属中学2025届高三上学期暑假测试物理试卷答案

分类:中学教育

时间:2026-01-20

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394