Isaac Asimov - Robot City 3 - Cyborg

IsaacAsimov'sRobotCityBook3:CyborgISAACASIMOV'SROBOTCITYBOOK3:CYBORGWILLIAMF.WUCopyright©1987ACKNOWLEDGMENTSSpecialthanksforhelpinwritingthisnovelareduetoDavidM.Harris,MichaelP.Kube-McDowell,RobChilson,AlisonTelure,myparents,Dr.WilliamQ.WuandCecileF.Wu,andPlusFiveComputerServices,Inc.Thisnovelisdedi...

相关推荐

-

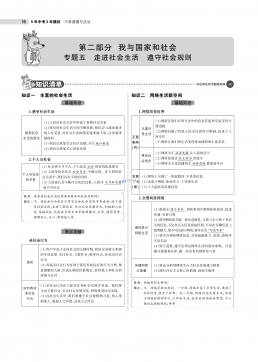

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包05专题五 走进社会生活 遵守社会规则VIP免费

2024-11-21 13

2024-11-21 13 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包05专题五 走进社会生活 遵守社会规则VIP免费

2024-11-21 11

2024-11-21 11 -

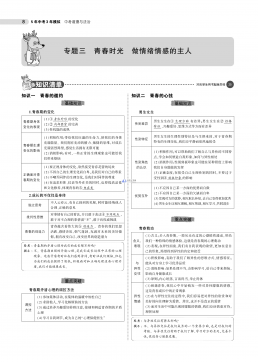

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包03专题三 青春时光 做情绪情感的主人VIP免费

2024-11-21 6

2024-11-21 6 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包03专题三 青春时光 做情绪情感的主人VIP免费

2024-11-21 8

2024-11-21 8 -

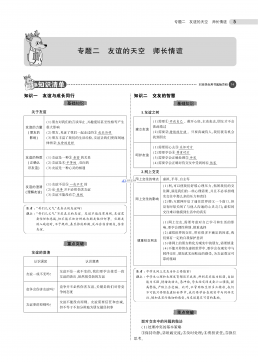

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包02专题二 友谊的天空 师长情谊VIP免费

2024-11-21 9

2024-11-21 9 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包02专题二 友谊的天空 师长情谊VIP免费

2024-11-21 8

2024-11-21 8 -

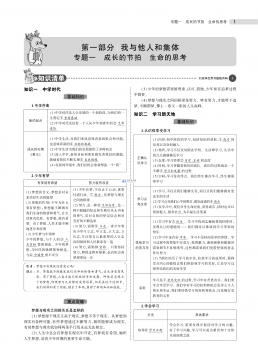

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包01专题一 成长的节拍 生命的思考VIP免费

2024-11-21 8

2024-11-21 8 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包01专题一 成长的节拍 生命的思考VIP免费

2024-11-21 8

2024-11-21 8 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包《53中考》全国道德与法治资料包VIP免费

2024-11-21 10

2024-11-21 10 -

曲一线系列初中《5中考3年模拟》2023专题解释全国道德与法治资料包07专题七 坚持宪法至上 崇尚法治精神VIP免费

2024-11-21 7

2024-11-21 7

作者详情

相关内容

-

2025年重庆市中考物理试题

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-11-26

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

2025年重庆市中考数学试题 (1)

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-11-26

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

2025年重庆市中考历史真题

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-11-26

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

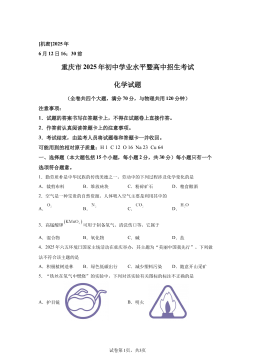

2025年重庆市中考化学真题

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-11-26

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

-

2025年重庆市中考道德与法治真题

分类:中学教育

时间:2025-11-26

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:10 玖币

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394