Blind Willie

VIP免费

2024-12-07

0

0

624.08KB

26 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

Life seems to have stood still in Tangier. It had grown old, it is true, but it has

not grown wiser or better. Or rather it seems not as if it had grown old, but as if it

had never been young. To an artist — and many artists visit Tangier — it must be

an enchanting place; but it would disgust a thrifty farmer or an enterprising

trader, and make every hair of an inspection of nuisances stand on end.

— AMELIA PERRIER, 1876

Founding Editor

PAUL BOWLES

Founding Publisher

DRUE HEINZ

Associate Publisher

JEANNE WILMOT CARTER

Managing Editor

ELLEN FOOS

Publicity & Marketing

WILLIAM CRAGER

LISA ANN WEISBROD

Production Manager

VINCENT JANOSKI

Assistant Editors

HEATHER WINTERER

CHRISTINA THOMPSON

Contributing Editors

ANDREAS BROWN JOHN HAWKES

JOHN FOWLES STANLEY KUNITZ

DONALD HALL W.S. MERWIN

MARK STRAND

Antaeus is published by The Ecco Press, 100 West Broad Street, Hopewell, NJ 08525

Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110, Ingram

Periodicals, 347 Reedwood Drive, Nashville, TN 37217, and B. DeBoer, Inc., 113 East Centre

St., Nutley, NJ 07110. Distributed in England & Europe by W.W. Norton & Compnay, Inc.

ANTAEUS

100 West Broad Street, Hopewell, NJ 08525

Back issues available — write for a complete listing

ISSN 0003-5319

ISBN 0-88001-392-3

Library of Congress Card Number: 70-612646

Copyright (c) 1995 by ANTAEUS, Hopewell, NJ

Cover art: Fresco from Giotto Chapel (detail)

Cover design: Lorraine Louie

Publications of this magazine has been made possible in part by a grant

From the National Endowment for the Arts.

Logo: Ahmed Yacoubi

STEPHEN KING

Blind Willie

6:15 A.M.

He wakes to music, always to music; the shrill beep-beep-beep of the clock-radio's alarm is too

much for his mind to cope with during those first blurry moments of the day. It sounds like a

dump truck backing up. The radio is bad enough at this time of year, though; the easy-listening

station he keeps the clock-radio tuned to is wall-to-wall Christmas carols, and this morning he

wakes up to one of the two or three on his Most Hated List, something full of breathy voices and

phony wonder. The Hare Krishna Chorale or the Andy Williams Singers or some such. Do you

hear what I hear, the breathy voices sing as he sits up in bed, blinking groggily, hair sticking out

in every direction. Do you see what I see, they sing as he swings his legs out, grimaces his way

across the cold floor to the radio, and bangs the button that turns it off. When he turns around,

Sharon has assumed her customary defensive posture — pillow folded over her head, nothing

showing but he creamy curve of one shoulder, a lacy nightgown strap, and a fluff of blonde hair.

He goes into the bathroom, closes the door, slips off the pajama bottoms he sleeps in, drops

them into the hamper, clicks on his electric razor. As he runs it over his face he thinks, Why not

run through the rest of the sensory catalogue while you're at it, boys? Do you smell what I smell,

do you taste what I taste, do you feel what I feel. I mean, hey, go for it.

'Humbug,' he says as he turns on the shower. 'All humbug.'

Twenty minutes later, while he's dressing (the dark grey suit from Paul Stuart this morning, plus

his favorite Sulka tie), Sharon wakes up a little. Not enough for him to fully understand what

she's telling him, though.

'Come again?' he asks. 'I got eggnog, but the rest was just ugga-wugga.'

'I asked if you'd pick up two quarts of eggnog on your way home,' she says. 'We've got the

Allens and the Dubrays coming over tonight, remember?

'Christmas,' he says, checking his hair carefully in the mirror. He no longer looks like the

glaring, bewildered man who sits up in bed to the sound of music five mornings a week —

sometimes six. Now he looks like all the other people who will ride into New York with him on

the 7:40, and that is just what he wants.

'What about Christmas?' she asks with a sleepy smile. 'Humbug, right?

'Right,' he agrees. 'All humbug.'

'If you remember, get some cinnamon too — '

'Okay.'

' — but if you forget the eggnog, I'll slaughter you, Bill.'

'I'll remember.'

'I know. You're very dependable. Look nice too.'

'Thanks.'

She flops back down, then props herself up on one elbow as he makes a final minute

adjustment to the tie, which is a dark blue. He has never worn a red tie in his life, and hopes he

can go to his grave untouched by that particular virus. 'I got the tinsel you wanted,' she says.

'Mmmmm?'

'The tinsel,' she says. 'It's on the kitchen table.'

'Oh.' Now he remembers. 'Thanks.'

'Sure.' She's back down and already starting to drift off again. He doesn't envy the fact that she

can stay in bed until nine — hell, until eleven, if she wants — but he envies that ability of hers to

wake up, talk, then drift off again. She says something else, but now she's back to ugga-wugga.

He knows what it is just the same, though: have a good day hon.

'Thanks,' he says, kissing her cheek. 'I will.'

'Look very nice,' she mumbles again, although her eyes are closed. 'Love you, Bill.'

'Love you too,' he says and goes out.

His briefcase — Mark Cross, not quite top of the line but almost — is standing in the front hall,

by the coat tree where his topcoat (from Barney's on Madison) hangs. He grabs the case on his

way by and takes it into the kitchen. The coffee is all made — God bless solid state electronics

and microchips — and he pours himself a cup. He opens the briefcase, which is entirely empty,

and picks up the ball of tinsel on the kitchen table. He holds it up for a moment, watching the

way it sparkles under the light of the kitchen fluorescents, then puts it in his briefcase.

'Do you hear what I hear,' he says to no one at all and snaps the briefcase shut.

8:15 A.M.

Outside the dirty window to his left, he can see the city drawing closer. The grime on the glass

makes it look like some filthy, gargantuan ruin — Atlantis, maybe, just heaved back to the

surface. It's a grey day with a load of snow caught in its throat, but that doesn't worry him much;

it is just eight days until Christmas, and business will be good.

The car reeks of morning coffee, morning deodorant, morning aftershave, morning perfume,

and morning stomachs. There is a tie in almost every seat — even the women wear them these

days it seems. The faces have that puffy eight o'clock look, the eyes both introspective and

defenseless, the conversations halfhearted. This is the hour at which even people who don't drink

look hung over. Most people just stick to their newspapers. He himself has the Times crossword

open in front of him, and although he's filled in a few squares, it's mostly a defensive measure.

He doesn't like to talk to people on the train, doesn't like loose conversation of any sort, and the

last thing in the world he wants is a commuter buddy. When he starts seeing the same faces in

any given car, when people start to nod to him or say 'How you doin today?' as they go to their

seats, he changes cars. It's not that hard to remain unknown, just another commuter, one who is

conspicuous only in his adamant refusal to wear a red tie. Not that hard at all.

'All ready for Christmas?' the man in the aisle seat asks him.

He looks up, almost frowning, then decides it's not a substantive remark, but only the sort of

empty time-passer some people seem to feel compelled to make. The man beside him is fat and

will undoubtedly stink by noon no matter how much Speed Stik he used this morning . . . but he's

hardly even looking at his seatmate, so that's all right.

'Yes, well, you know,' he says, looking down at the briefcase between his shoes — the

briefcase that contains a ball of tinsel and nothing else. 'I'm getting in the spirit, little by little.'

8:40 A.M.

He comes out of Penn Station with a thousand other topcoated commuters and commuterettes,

mid-level executives for the most part, sleek gerbils who will be running full tilt on their exercise

wheels by noon. He stands still for a moment, breathing deep of the cold grey air. Madison

Square Garden has been tricked out with greenery and Christmas lights, and a little distance

away a Santa Claus who looks Puerto Rican is ringing a bell. He's got a pot for contributions

with an easel set up beside it. HELP THE HOMELESS THIS CHRISTMAS, the sign on the

easel says, and the man in the blue tie thinks, How about a little truth in advertising, Santa? How

about a sign that says, HELP ME SUPPORT MY CRACK HABIT THIS CHRISTMAS?

Nevertheless, he drops a couple of dollar bills into the pot as he walks past. He has a good

feeling about today. He's glad Sharon remembered the tinsel — he would have forgotten,

himself; he always forgets stuff like that, the grace notes.

He walks five short blocks and then comes to his building. Standing outside the door is a young

black man — a youth, actually, surely no more than seventeen — wearing black jeans and a dirty

red sweater with a hood. He jives from foot to foot, blowing puffs of steam out of his mouth,

smiling frequently, showing a gold tooth. In one hand he holds a partly crushed Styrofoam coffee

cup. There's some change in it, which he rattles constantly.

'Spare a little?' he asks the passersby as they stream toward the revolving doors. 'Spare a little,

sir? Spare a little, ma'am? Just trying to get lil spot of breffus. Than you, gobless you, merry

Christmas. Spare a little, sir? Quarter, maybe? Than you. Spare a little, ma'am?'

As he passes, Bill drops a nickel and two dimes into the young black man's cup.

'Thank you, sir, gobless, merry Christmas.'

'You, too,' he says.

The woman next to him frowns. 'You shouldn't encourage them,' she says.

He gives her a shrug and a small, shamefaced smile. 'It's hard for me to say no to anyone at

Christmas,' he tells her.

He enters the lobby with a stream of others, stares briefly after the opinionated bitch as she

heads for the newsstand, then goes to the elevators with their old-fashioned floor dials and their

art deco numbers. Here several people nod to him, and he exchanges a few words with a couple

of them as they wait — it's not like the train, after all, where you can change cars. Plus, the

building is an old one, only fifteen stories high, and the elevators are cranky.

'How's the wife, Bill?' a scrawny, constantly grinning man from the fifth floor asks.

'Andi? She's fine.'

'Kids?'

'Both good.' He has no kids, of course — he wants kids about as much as he wants a hiatal

hernia — and his wife's name isn't Andi, but those are things the scrawny, constantly grinning

man will never know.

'Bet they can't wait for the big day,' the scrawny man says, his grin widening and becoming

unspeakable. Now he looks like an editorial cartoonist's conception of Famine, all big eyes and

huge teeth and shiny skin.

'That's right,' he says, 'but I think Sarah's getting kind of suspicious about the guy in the red

suit.' Hurry up, elevator he thinks, Jesus, hurry up and save me from these stupidities.

'Yeah, yeah, it happens,' the scrawny man says. His grin fades for a moment, as if they are

discussing cancer instead of Santa. 'How old's she now?'

'Eight.'

'Boy, the time sure flies when you're having fun, doesn't it? Seems like she was just born a

year or two ago.'

'You can say that again,' he says, fervently hoping the scrawny man won't say it again. At that

moment one of the four elevators finally gasps open its doors and they herd themselves inside.

Bill and the scrawny man walk a little way down the fifth floor hall together, and then the

scrawny man stops in front of a set of old-fashioned double doors with the words

CONSOLIDATED INSURANCE written on one frosted-glass panel and ADJUSTORS OF

AMERICA on the other. From behind these doors comes the muted clickety-click of computer

keyboards and the slightly louder sound of ringing phones.

'Have a good day, Bill.'

'You too.'

The scrawny man lets himself into his office, and for a moment Bill sees a big wreath hung on

the far side of the room. Also, the windows have been decorated with the kind of snow that

comes in a spray can. He shudders and thinks, God save us, every one.

9:05 A.M

His office — one of two he keeps in this building — is at the far end of the hall. The two offices

up from it are dark and vacant, a situation that has held for the last six months and one he likes

just fine. Printed on the frosted glass of his own office door are the words WESTERN STATES

LAND ANALYSTS. There are three locks on the door: the one that was on it when he moved

into the building nine years ago, plus two he has put on himself. He lets himself in, closes the

door, turns the bolt, then engages the police lock.

A desk stands in the center of the room, and it is cluttered with papers, but none of them mean

anything; they are simply window dressing for the cleaning service. Every so often he throws

them all out and redistributes a fresh batch. In the center of the desk is a telephone on which he

makes occasional random calls so that the phone company won't register the line as totally

inactive. Last year he purchased a fax, and it looks very businesslike over in its corner by the

door to the office's little second room, but it has never been used.

'Do you hear what I hear, do you smell what I smell, do you taste what I taste,' he murmurs,

and crosses to the door leading to the second room. Inside are shelves stacked high with more

meaningless paper, two large file cabinets (there is a Walkman on top of one, his excuse on the

few occasions when someone knocks on the locked door and gets no answer), a chair, and a

stepladder.

Bill takes the stepladder back to the main room and unfolds it to the left of the desk. He puts

his briefcase on top of it. Then he mounts the first three steps of the ladder, reaches up (the

bottom half of his coat bells out around his legs as he does), and carefully moves aside one of the

suspended ceiling panels.

Above is a dark area which cannot quite be called a utility space, although a few pipes and

wires do run through it. There's no dust up here, at least not in this immediate area, and no rodent

droppings, either — he uses D-Con Mouseprufe once a month. He wants to keep his clothes nice

as he goes back and forth, of course, but that's not really the important part. the important part is

to respect your work and your field. This he learned in the Marines, and he sometimes thinks it is

the most important thing he did learn there. He stayed alive, of course, but he thinks now that

was probably more luck than learning. Still, a person who respects his work and his field — the

place where the work is done, the tools with which it is done — has a leg up in life. No doubt

about that.

Above this narrow space (a ghostly, gentle wind hoots endlessly through it, bringing a smell of

dust and the groan of the elevators) is the bottom of the sixth floor, and here is a square trap door

about thirty inches on a side. Bill installed it himself; he's handy with tools, which is one of the

things Sharon most appreciates about him.

He flips the trap door up, letting in muted light from above, then grabs his briefcase by the

handle. As he sticks his head into the space between the floors, water rushes gustily down the fat

bathroom conduit twenty or thirty feet north of his present position. An hour from now, when the

people in the building start their coffee breaks, that sound will be as constant and as rhythmic as

waves breaking on a beach. Bill hardly notices this or any of the other interfloor sounds; he's

used to them.

He climbs carefully to the top of the stepladder, then boosts himself through into his sixth

floor office, leaving Bill down on five. Up here he is Willie. This office has a workshop look,

with coils and motors and vents stacked neatly on metal shelves and what looks like a filter of

some kind squatting on one corner of the desk. It is an office, however; there's a computer

terminal, an IN/OUT basket full of papers (also window dressing, which he periodically rotates

like a farmer rotating crops), and file cabinets. On one wall is a framed Norman Rockwell print

showing a family praying over Thanksgiving dinner. Next to it is a blowup of his honorable

discharge from the marines, also framed; the name on the sheet is William Teale, and his

decorations, including the Bronze Star, are duly noted. On another wall is a poster from the

sixties. It shows the peace sign. Below it, in red, white, and blue, is this punchline: TRACK OF

THE GREAT AMERICAN CHICKEN.

Willie puts Bill's briefcase on the desk, then lies down on his stomach. He pokes his head and

arms into the windy, oil-smelling darkness between the floors and replaces the ceiling panel of

the fifth-floor office. it's locked up tight, he doesn't expect anyone anyway (he never does;

Western States Land Analysts has never had a single customer), but it's better to be safe. Always

safe, never sorry.

With his fifth floor office set to rights, Willie lowers the trapdoor in this one. Up here the trap

is hidden by a small rug which is Superglued to the wood, so it can go up and down without too

much flopping or sliding around.

He gets to his feet, dusts off his hands, then turns to the briefcase and opens it. He takes out

the ball of tinsel and puts it on top of the laser printer which stand nest to the computer terminal.

'Good one,' he says, thinking again that Sharon can be a real peach when she sets her mind to

it . . . and she often does. He relatches the briefcase and then begins to undress, doing it carefully

and methodically, reversing the steps he took at six-thirty, running the film backward. He strips

off everything, even his undershorts and his black, knee-high socks. Naked, he hangs his topcoat,

suit jacket, and shirt carefully in the closet where only one other item hangs — a bulky red thing,

a little too bulky to be termed a briefcase. Willie puts his mark Cross case next to it, then places

his slacks in the pants press, taking pains with the crease. The tie goes on the rack screwed to the

back of the closet door, where it hangs all by itself like a long blue tongue.

He pads barefoot-naked across to one of the file cabinets. On top of it is an ashtray embossed

with a pissed-off-looking eagle and the Marine motto. In it are a pair of dogtags on a chain.

Willie slips the chain over his head, then slides out the bottom drawer of the cabinet stack. Inside

are underclothes. Neatly folded on top are a pair of khaki boxer shorts. He slips them on. Next

come white athletic socks, followed by a white cotton T-shirt — roundneck, not strappy. The

shapes of his dog-tags stand out against it as do his biceps and quads. They aren't as good as they

were in '67, under the triple canopy, but they aren't bad. As he slides the drawer back in and

opens the next, he begins to hum under his breath — not 'Do You Hear What I Hear' but the

Doors, the one about how the day destroys the night, the night divides the day.

He slips on a plain blue chambray shirt, then a pair of fatigue pants. He rolls this middle

drawer back in and opens the top one. Here there is a pair of black boots, polished to a high

sheen and looking as if they might last until the trump of judgement. Maybe even longer. They

aren't standard Marine issue, not these — these are jumpboots, 101st Airborne stuff. But that's all

right. He isn't actually trying to dress like a soldier. If he wanted to dress like a soldier, he would.

Still, there is no more reason to look sloppy than there is to allow dust to collect in the pass-

through, and he's careful about the way he dresses. He does not tuck his pants into his boots, of

course — he's headed for Fifth Avenue in December, not the Mekong in August — but he

intends to look squared away. Looking god is as important to him as it is to Bill, maybe even

more important. Respecting one's work an one's filed begins, after all, with respecting one's self.

The last two items are in the back of the top drawer: a tube of makeup and a jar of hair gel. He

squeezes some of the makeup into the palm of his left hand, then begins applying it, working

from forehead to the base of his neck. He moves with the unconcerned speed of long experience,

giving himself a moderate tan. With that done, he works some of the gel into his hair and then

recombs it, getting rid of the part and sweeping it straight back from his forehead. It is the last

touch, the smallest touch, and perhaps the most telling touch. There is no trace of the commuter

who walked out of Penn Station an hour ago; the man in the mirror mounted on the back of the

door to the small storage annex looks like a washed-up mercenary. There is a kind of silent, half-

humbled pride in the tanned face, something people won't look at too long. It hurts them if they

do. Willie knows this is so; he has seen it. He doesn't ask why it should be so. He has made

himself a life pretty much without questions, and that's the way he likes it.

'All right,' he says, closing the door to the storage room. 'Lookin good, trooper.'

He goes back to the closet for the red jacket, which is the reversible type, and the boxy case.

He slips the jacket over his desk chair for the time being and puts the case on the desk. He

unlatches it and swings the top up on sturdy hinges; now it looks a little like the cases the street

salesmen use to display their cheap watches and costume jewelry. There are only a few items in

Willie's, one of them broken down into two pieces so it will fit. He takes out a pair of gloves (he

will want them today, no doubt about that), and then a sign on a length of stout cord. The cord

has been knotted through holes in the cardboard at either side, so Willie can hang the sign over

his neck. He closes the case again, not bothering to latch it, and puts the sign on top of it — the

desk is so cluttery, it's the only good surface he has to work on.

Humming (we chased our pleasure here, dug our treasures there), he opens the wide drawer

above the kneehole, paws past the pencils and Chapsticks and paper clips and memo pads, and

finally finds his stapler. He then unrolls the ball of tinsel, places it carefully around the rectangle

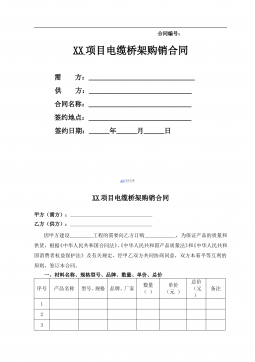

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

LifeseemstohavestoodstillinTangier.Ithadgrownold,itistrue,butithasnotgrownwiserorbetter.Orratheritseemsnotasifithadgrownold,butasifithadneverbeenyoung.Toanartist—andmanyartistsvisitTangier—itmustbeanenchantingplace;butitwoulddisgustathriftyfarmeroranenterprisingtrader,andmakeeveryhairofaninspectiono...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:26 页

大小:624.08KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-07

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394