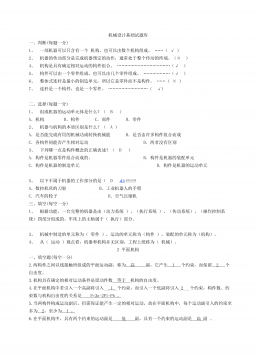

setup acc

neural captions, 0-shot 27.9

human captions, 0-shot 17.4

human captions, Krojer et al’s best 22.3

Table 1: Percentage IMAGECODEaccuracy of 0-

shot image retriever when given neural vs. human cap-

tions as input. Last row reports accuracy of best fine-

tuned, architecturally-adjusted model from Krojer et al.

(2022) (featuring a context module, temporal embed-

dings and a ViT-B/16 backbone).

data-set (Lin et al.,2014), where the weights of

the multimodal mapper were updated and those of

the language model (GPT-2) were kept frozen. We

obtained very similar results with the other publicly

available ClipCap variants. We generate a single

neural caption for each IMAGECODEtarget image

by passing it through ClipCap. Note that, as there

is no way to make this out-of-the-box architecture

distractor-aware, the neural captions do not take

distractors into account.

Image retrieval

We use the simplest architecture

proposed by Krojer et al. (2022) (the one without

context module and temporal embeddings), which

amounts to a standard CLIP retriever from Rad-

ford et al. (2021). The caption and each image in

the set are passed through textual and visual en-

coders, respectively. Retrieval is successful if the

dot product between the resulting caption and tar-

get image representations is larger than that of the

embedded caption with any distractor representa-

tion. We use the ResNet-based CLIP visual encoder

(He et al.,2015), whereas Krojer et al. (2022) used

the ViT-B/16 architecture. We found the former

to have a slightly higher 0-shot retrieval accuracy

compared to the one they used (17.4% in Table 1

here vs. 14.9% in their paper).

3 Results and analysis

Neural vs. human caption performance

As

shown in Table 1, the out-of-the-box neural image

retrieval model has a clear preference for neural

captions. It reaches 27.9% IMAGECODEaccuracy

when taking neural captions as input, vs. 17.4%

with human captions (chance level is at 10%).

For comparison, the best fine-tuned, architecture-

adjusted model of Krojer et al. (2022) reached

22.3% performance with human captions.

A concrete sense of the differences between the

two types of captions is given by the examples in

Fig. 1. The examples in this figure are picked ran-

domly. Based on manual inspection of a larger

set, we are confident they are representative of

the full data. Clearly, neural captions are shorter

(avg. length at 11.4 tokens vs. 23.2 for human

captions) and more plainly descriptive (although

the description is mostly only vaguely related to

what’s actually depicted). Since there is no way to

make the out-of-the-box ClipCap system distractor-

aware, the neural captions are not highlighting dis-

criminative aspects of a target image compared to

the distractors. Human captions, on the other hand,

use very articulated language to highlight what is

unique about the target compared to the closest dis-

tractors (often focusing on rather marginal aspects

of the image, because of their discriminativeness,

e.g., for the first example in the figure, the fact that

the blue backpack is hardly visible). It is not sur-

prising that a generic image retriever, that was not

trained to handle this highly context-based linguis-

tic style, would not get much useful information out

of the human captions. It is interesting, however,

that this generic system performs relatively well

with the neural captions, given how off-the-mark

and non-discriminative the latter typically are.

As more quantitative cues of the differences be-

tween caption types, we observe that human cap-

tions are making more use of both rare lemmas

and function words (see frequency plots in Ap-

pendix B).

2

Extracting the lemmas that are statisti-

cally most strongly associated to the human caption

set (see Appendix Cfor method and full top list),

we observe “meta-visual” words such as visible

and see, pronouns and determiners cuing anaphoric

structure (the,her,his), and function words sig-

naling a more complex sentence structure, such

as auxiliaries, negation and connectives. Among

the most typical neural lemmas, we find instead

general terms for concrete entities such as people,

woman,table and food.

Are neural captions really discriminative?

By

looking at Figure 1, we see that neural captions

might be (very noisily) descriptive of the target, but

they seem hardly discriminative with respect to the

nearest distractors. Recall that each IMAGECODE

set contains a sequence of 10 frames from the same

scene. In general, the frames that are farther away

in time might be easier to discriminate than the

2

Code to reproduce our analysis with human and model-

generated captions is available at

https://github.com/

franfranz/emecomm_context

2024-11-15 27

2024-11-15 27

2024-11-15 16

2024-11-15 16

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 6

2025-04-07 6

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394