A. E. Van Vogt - Rogue Ship

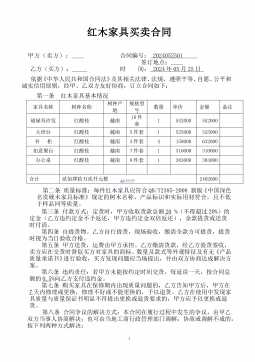

VIP免费

2024-12-24

0

0

342.55KB

121 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

Rogue Ship

By A. E. Van Vogt

Granada Publishing Limited

Published in 1975 by Panther Books Ltd

Frogmore, St Albans, Herts AL2 2NF

First published in Great Britain by Dobson Books Ltd 1967

'Centaurus II' was originally published inAstounding Science Fiction (nowANALOG Science Fact –

Science Fiction), 'Rogue Ship' was originally published inSuper-Science Stories, and 'The Expendables'

was originally published inIF Worlds of Science Fiction, 1947, 1950, and

1963, respectively. All three of these stories have been completely rewritten into this 'novel' form.

Copyright © A. E. van Vogt 1965

Made and printed in Great Britain by Richard Clay (The Chaucer Press) Ltd

Bungay, Suffolk

Set in Linotype Plantin

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold,

hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any

form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar

condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

This book is published at a net price and is supplied subject to the Publishers Association

Standard Conditions of Sale registered under the Restrictive Trade Practices Act, 1956.

DEDICATION

For Ford McCormack, friend, logician, technical expert, man of many parts, who seems to be as much

at home in the exotic universe of translight speeds as on the stage of important little theaters - to whom I

am indebted for some of the concepts and for nearly all of what is scientifically exact in this fantastic

story.

I

Out of the corner of one eye, young Lesbee saw Ganarette climbing the steps that led to the spaceship's

bridge. He felt vaguely annoyed. Ganarette, at nineteen, was a big, husky youth with a square jaw and

belligerent manner. Like Lesbee himself, he had been born on the ship. As a non-officer, he was not

allowed on the bridge and it was that, entirely aside from his own personal dislike of Ganarette, that

annoyed Lesbee about the intrusion.

Besides, he was scheduled to go off duty in five minutes.

Ganarette mounted the final step, and climbed gingerly down to the cushiony floor. He must have been

intent on his descent, for when he looked up and saw the black, starry heavens, he gasped and then

stood teetering a dozen feet from Lesbee, staring into the darkness. His reaction startled Lesbee. It

hadn't struck him before, but there were actually people on this ship whose only view of space had been

by way of the visiscreen.

The sheer, stark reality of the plastiglass bridge, with its effect of standing there in the dark, empty space

itself, must be mind-staggering. Lesbee had a vague feeling of superiority. He had been allowed on the

bridge since early childhood.

To him, what was out there seemed as natural and ordinary as the ship itself.

He saw that Ganarette was recovering from his initial shock. 'So,' Ganarette said, 'this is what it's really

like. Which is Centaurus?'

Stiffly, Lesbee pointed out the very bright star which was visible beyond the sight lines of the astrogation

devices. Since nonmilitary personnel were never permitted on the bridge, he wondered if he were

obligated to report the youth's intrusion.

He felt reluctant to do so, first of all because it might antagonize the other young people aboard. As the

captain's son, be was already being treated as a person set apart. If he defi-nitely aligned himself with the

ship authority, he might find himself even more cut off.

He had a sudden mental picture of himself repeating his father's lonely existence.

He shook his head ever so slightly, silently rejecting that way of life.

In a few minutes his period of duty for the day would be over. At that point he would lead Ganarette

gently but firmly down the steps and give him as friendly a warning as possible. He saw that the youth

was looking at him with a faint, cynical smile.

'Doesn't look very close. Boy, they sure pulled a trick on the colonists, pretending the ship was going to

make the trip at the speed of light or faster and get there in four years.' Ganarette's tone was sarcastic.

'Nine more years,' Lesbee said, 'and we'll be there.'

'Yeah!' Cynically. "That I have to see.' He broke off. 'And which is Earth?'

Lesbee led him to the other side of the bridge to a sighting device that was always aimed at Earth's sun.

The pale star held Ganarette's interest for nearly a minute. His face changed; gloom was written there.

He slumped a little, then whispered, 'It's so far away, so very far away. If we started back now, you and

I would be forty years old when we got there.'

He whirled and firmly grasped Lesbee's shoulders. Think of it!' he said. 'Forty years old. Half of our

lifetime gone, but still a chance to have a little fun - if we turned back this instant.'

Lesbee freed himself from the clamping fingers. He was disturbed. It was more than a year since he had

heard that kind of talk from any of the younger folk. Ever since his father initiated the lectures on the

importance of this, the second voyage to Alpha Centauri, the wilder spirits among the young people had

quieted down.

Ganarette seemed to realize that his action had been foolish.

He stepped back with a sheepish grin. Once more he became satiric. He said, 'But of course it would be

silly to turn back now when we're only nine years from Centaurus, a mere eighteen years farther from

Earth, there and return.'

Lesbee did not ask, return to what? Long ago, most of those aboard had ceased to regard the original

purpose of the voyage as having meaning. There was the sun, wasn't there, with no visible change? And

so there must be an Earth to return to. Lesbee knew that among the young people his father was

con-sidered to be an old fool who dared not go back to face the ridicule of his fellow scientists. The

pride of this foolish old man was continuing to force a shipload of people to spend the equivalent of a

normal lifetime in space. Lesbee had often felt the horror at such a prospect that Ganarette was now

express-ing, and he could not help but share some of the condemnation of his father.

Trembling, he looked at his watch. He was relieved to see that it was time to switch on the automatic

pilot. His duty period was over. He turned, manipulated the control switches, counted the lights that went

on, cross-checked with the two physicists in the engine room, and then, as he always did, made a second

count of the lights. They were still exactly right. For twelve hours now, electronic machinery would guide

the ship. Then Carson would assume the watch for six hours. The first officer would be followed, after

twelve more hours, by the second officer who, in turn, would be succeeded by Browne, the third officer.

And then, when still another twelve hours of automatic flight had gone by, it would be his turn again.

Such was the pattern of his life, and so it had been since his fourteenth birthday. It was certainly not a

hard existence. The ship's top officers actually had an easy time of it. But each man was jealous of his

duty stint, and always showed up on the dot. A few years ago, Browne had even had himself wheeled to

the upper deck in a wheelchair and then assisted to the bridge by his son, who had remained with his sick

father during the entire six hours.

Such devotion to duty puzzled young Lesbee, and so he had made one of his rare efforts to

communicate with his father, asking him what could have motivated Browne. The old man smiled at him

quizzically, and explained, 'Going on watch is the status symbol of every officer, so don't ever regard it

lightly. They don't, as Browne is demonstrating. We are the official ruling class, my boy. Treat all those

men with respect, use their formal titles, and in return they'll recognize your status. Whatever benefits

accrue to the nobility aboard this ship will depend on how well we maintain such amenities.'

Lesbee had already discovered that several of the benefits were that the prettiest girls smiled at him, and

came running when he smiled back.

Recalling the smiles of one girl in particular, he emerged from his reverie and realized that he would

barely have time to wash up before the movie started.

He grew aware that Ganarette was looking at the clock on the low-built control board. The young man

faced Lesbee. 'O.K., John,' he said, 'you might as well get it now. Five minutes after the motion picture

starts my group is taking over the ship. We intend to make you captain, but only on the condition that you

agree to turn back to Earth. We won't hurt any of the old fogies - if they behave. If they act up, there'll be

as much trouble as they want. If you try to warn anybody, we shall reconsider our plan to make you

captain.'

Ignoring Lesbee's dumbfounded reaction, he went on, 'Our problem is to make sure that we don't do

anything that might arouse suspicion. That means everybody, including you, should carry on as always.

What do you normally do when you leave the bridge?'

'I go to my quarters and wash up,' said Lesbee, truthfully.

He was beginning to recover from the enormous shock of the other man's pronouncement. He grew

aware that he was in a state of anguish, and that amazingly what he felt was an awful anxiety that 'these

fools' - he muttered the words under his breath - would somehow mess up their mutiny, and this mad

voyage would continue on into infinity. As he realized his in-stant sympathy with the rebels, Lesbee

swallowed, and ab-ruptly felt confused.

Before he could recover, Ganarette said reluctantly, 'All

right - but I'll go with you.'

'Maybe it'd be better if I skipped going home,' said Lesbee doubtfully.

'And have your father become suspicious! Nothing doing!'

Lesbee was uneasy. He was, he realized, falling in with the plot. He sensed unknown dangers in that

direction. Yet the emotion that had broken through from ahidden depth of his being, was still driving him

on. He said in a conspiratorial tone, 'That would be preferable to having him wonder what I'm doing with

you. He doesn't like you.'

'Oh, he doesn't!' Ganarette sounded belligerent, but sud-denly he looked unsure of himself. 'All right,

we'll go straight down to the theater. But remember what I said. Watch your-self. Be as surprised as the

others, but be prepared to step in and take command.'

He impulsively put his hand on Lesbee's arm. 'We've got to win,' he said. 'My God, we've got to.'

As they went down into the ship a minute later, Lesbee found that he was somehow tightening his

muscles, bracing himself as for a struggle.

2

Lesbee sank into his seat. As he sat there, he grew aware that all around him in the theater, people were

fumbling their way to their places. He had time for doubt, for second thought. If he was going to do

anything, he would have to act swiftly.

Ganarette, who had been in the aisle whispering to another young man, crushed into the seat beside him.

He leaned to-ward Lesbee. 'Only a few minutes now, as soon as everybody is in. When the doors close,

we'll let the lights go off and the picture get started. Then in the darkness I'll make my way to the stage.

The moment the lights go on, you join me.'

Lesbee nodded, but he was unhappy. Only a short time had gone by since the great rush of sympathy

for the rebellion, but now that feeling was fading, replaced by an uneasy fear of consequences. He had no

conscious picture of what might hap-pen. It was an overall and growing sense of doom.

A buzzer sounded. 'Ah,' whispered Ganarette, 'the picture is going to start.'

The time was passing inexorably. The internal pressure to act was strong in Lesbee. He had a terrible

conviction that he was ruining himself with the authority group aboard, and that on the other hand the

mutineers merely intended to use him during the early stages of their rebellion, that later he would be

discarded. Abruptly, he was convinced that he had nothing to gain by their victory.

In a sudden desperation, he stirred in his seat, and looked around tensely, wondering if he couldn't

escape.

He gave that up after one quick look. His eyes had ac-customed to the night of the theater and it wasn't

really dark at all. Over to one side he could see Third Officer Browne and his wife sitting together. The

older man caught his distracted gaze and nodded.

Lesbee grimaced an acknowledging smile, then turned away. Beside him, Ganarette said, 'Where's

Carson?'

It was Lesbee's seeking gaze that found First Officer Carson sitting near the back of the theater, and it

was he who located the second officer slumped down in one of the seats near the front. Of the senior

officers of the ship only Captain Lesbee himself had not yet arrived. That was a little disquieting but

Lesbee took assurance from the fact that the theater had its normal packed appearance.

Three times a 'week' there was a show. Three times a week the eight hundred people on the ship

gathered in this room and gazed silently at the scenes of far-off Earth that glided over the screen. Seldom

did anyone miss the show. His father would be along any minute.

Lesbee settled himself to the inevitability of what was about to happen. On the screen a light flickered,

and then there was a burble of music. A voice said something about an 'important trial,' and then there

were several panels of printed words and a list of technical experts. At that point Lesbee's mind and gaze

wandered back to his father's reserved seat.

It was still empty.

The shock of that was not an ordinary sensation. It was an impact, astonishment mingled with a sense of

imminent dis-aster, the sudden tremendous conviction that his father knew of the plot.

He felt his first disappointment. It was an anguish of bitter emotion, the realization that the trip would go

on. His feelings caught him by surprise. He still hadn't realized the depth and intensity of his own

frustration aboard this ship, seven thousand and eight hundred days out from Earth. He whirled to

word-lash Ganarette for having made such a mess of the plot.

Lips parted, he hesitated. If the rebellion were destined to fail, it wouldn't do to have made a single

favorable remark about it. With a sigh he settled back in his seat. The anger passed and he could feel the

disappointment fading. Rising in its place was acceptance of the inevitability of the future.

On the screen somebody was standing before a jury and saying,'... the crime of this man is treason. The

laws of Earth do not pause inside the stratosphere or at the moon or at Mars—'

Once again the words and the scene couldn't hold Lesbee. His gaze flashed to Captain Lesbee's seat. A

sigh escaped from his lips as he saw that his father was in the act of sitting down. So he hadn't really

suspected. His late arrival was a meaning-less accident.

Within seconds the lights would flash on and the young rebels would take over the ship.

Curiously, now that there was no chance of his doing any-thing, he was able for the first time to give his

attention to the motion picture. It was as if his mind were anxious to escape from the sense of guilt that

was beginning to build up inside his body. He looked outside rather than in.

The scene was still a courtroom. A very pale young man was standing before a judge who wore a black

cap, and the judge was saying, 'Have you any final words before sentence is pro-nounced upon you?'

The reply was haltingly delivered: 'Nothing, sir ... except we were so far out.... It didn't seem as if we

had any connec-tion with Earth - After seven years, it just didn't seem pos-sible that the laws of Earth

had any meaning —'

It struck Lesbee that the theater was deathly quiet, and that the rebellion was many minutes overdue. It

was then as he listened to the final words of the judge that he realized that there would be no rebellion,

and why. The judge in that re-mote Earth court was saying:

'I have no alternative but to sentence you to death ... for mutiny.'

It was several hours later when Lesbee made his way to the projection room. 'Hello, Mr. Jonathan,' he

said to the slim, middle-aged man who was busily putting away his cans.

Jonathan acknowledged the greeting politely. But his face showed wonder that the captain's son should

have sought him out. His expression was a reminder to Lesbee that it didn't pay to neglectany one

aboard a ship, not even people you con-sidered unimportant.

'Odd picture you showed there at the beginning,' he said casually.

'Yeah.' The cans were being shoved into their protective cases. 'Kind of surprised me when your dad

phoned up and asked me to show it. Very old, you know. From the early days of interplanetary travel.'

Lesbee did not trust himself to speak. He nodded, pre-tended to inspect the room, and then went out -

scarcely look-ing where he was going.

For an hour he wandered around the ship and, gradually, a coherent purpose formed in his mind. He

must see his father.

That was unique because he had not spoken to his father except in monosyllables since his mother's

death.

3

He found the old man in the spacious living room of the apart-ment the two of them shared. At

seventy-odd, John Lesbee had learned to keep his counsel, so he merely glanced up when his son

entered, greeted him courteously, and resumed reading.

A minute went by before the father grew aware that his son had not gone on to his own bedroom. He

glanced up again, surprised now. 'Yes?' he said. 'Anything I can do for you?'

Young Lesbee hesitated. A formless emotion was upon him, a desire to be at peace with the other. He

had never forgiven his father for the death of his mother.

He said abruptly, 'Dad, why did Mother kill herself?'

Captain Lesbee put down his book. He seemed suddenly paler, though the color was hard to judge on a

face that was naturally gray-white. He drew a slow, deep breath. 'We-e-l-ll,' he said, 'what a question!'

His voice sounded breathless, and his eyes were bright.

'I think I should know,' Lesbee persisted.

There was silence - that lengthened. The lined face of the old man continued to be colorless; his eyes

remained un-naturally bright.

Lesbee II went on, 'She used to talk to me in a bitter way, all against you, but I never understood it.'

Captain Lesbee was nodding, half to himself. He seemed to have come to a decision, for he

straightened. 'I took advantage of her,' he said evenly. 'She was my ward, and as she grew older she

became attractive to me as a woman and I felt desire. Under normal circumstances I should have kept

such feelings to myself, and she would normally have gone off and married some young man of her own

generation. But I convinced my-self that she would at least be alive if she went with me. In this way, I

betrayed her trust in me, which was that of a child for a father and not that of a woman for her lover.'

Since he had never thought of his mother as being parti-cularly young, Lesbee II found it difficult to

grasp that this was what had caused her to have such intense emotions. Yet he recognized that he had

been given an honest statement. None-theless, it was a moment for all the truth, not just a part of it, and

so he went on: 'She used to call you stupid and' - he hesitated - 'and other things. One thing you're not is

stupid. But, sir, Mother swore to me that the death of Mr. Tellier was not an accident, as you said. She,

uh, called you a murderer.'

The color was creeping into his father's cheeks, an ever so faint flush. The old man sat for a long

moment, smiling faintly. Then: 'Only time will tell, Johnny, whether I'm a genius or a fool. I proved more

than a match for Tellier but that was because he had to nerve himself for each step, and with my greater

experience I could see what was coming next. Someday, I'll tell you about that long, drawn-out struggle.

With his knowledge of the equipment aboard, he could have defeated me. But he was never quite as

strongly motivated as I was.'

He must have realized the explanation was too generalized, for he continued after only a moment: 'I can

explain it all in a few sentences. On takeoff, Tellier took it for granted that we would be able to attain

very nearly the speed of light and so obtain the benefits predicted by the Lorentz-Fitzgerald Con-traction

Theory. We couldn't do it - as you know. The drive fell far short of Tellier's theoretical expectations. As

soon as he realized that we were in for a long voyage, he wanted to turn back. Naturally, I couldn't let

him do that. He thereupon went into a state of mind verging on the psychotic, and he was in that

condition when he had his accident.'

'Why would Mother hold that against you?'

The elder Lesbee shrugged. Something of that long-ago im-patience he must have felt, thickened his

voice as he said, 'Your mother never did understand what Tellier and I were wrangling about, in terms of

its scientific meaning. But she did know that he wanted to turn back. Since she wanted that also, she

maintained that his knowledge as an astrophysicist was superior to mine as a mere astronomer, and that,

therefore, I was stupidly opposing the views of a man who really knew the facts.'

'I see.' Young Lesbee was silent, then: 'I've never under-stood the Lorentz-Fitzgerald Contraction

Theory, nor what it was that you discovered about the sun that made you under-take this voyage.'

The older man looked at him thoughtfully. 'It's a long, in-volved idea,' he said. Tor example, it's not the

sun itself but a warp in space which I analyzed. This warp should by now have caused the destruction of

the solar system.'

'But the sun didn't flare up.'

'I never said it would,' said his father in an irritated tone.' He broke off: 'My boy, you'll find my detailed

report among the ship's scientific papers, and also available is Dr. Tellier's account of his experiments in

attempting to reach high speed. His papers contain a description of the famous Lorentz-Fitzgerald

Contraction Theory. Why don't you read it all when you have time.'

The youth hesitated. He was not eager to hear a long, scientific account, particularly at this hour of the

night. But he recognized that this communication with his father was taking place because he himself was

in an overstimulated condition; it might be a one-time occurrence. And so, after a moment, he persisted:

'But why didn't the ship speed up as predicted? What went wrong?'

He added quickly, 'Oh, I realize lectures were given on the subject but, knowing you, I feel that they

were what you wanted people to believe in the interests of the voyage. What's the truth?'

The old man's eyes twinkled suddenly, then he chuckled. 'I really turned out to have a natural instinct for

knowing how to maintain discipline and morale, didn't I?' He grew somber. 'I wish I could inject some of

that into you.' He broke off. 'But never mind. Your observation is correct. I told the people what I

wanted them to think. The actual truth is substantially what I have already told you. When Tellier

discovered that the ejected particles could not be speeded up to the point where they would expand, it

became necessary to conserve our fuel supply. Theoretically, particles expanded to the level pre-dicted

for them at the velocity of light would have given us almost infinite power on a thimbleful of fuel. As it is,

we used up hundreds of tons of fuel to get the ship up to 15 per cent of light-speed. Since by that time,

we could calculate our fuel situation in terms of simple additive and subtractive arith-metic, I ordered the

engines shut off. We've been coasting ever since at that speed. We'll have to use an equal amount of fuel

tonnage to slow down when we get to Centaurus. If things work out when we arrive there, then, of

course, no problem. But if they don't, then somewhere, sometime, we're going to pay the price for

Tellier's failure.'

'What price?' Lesbee II asked.

'No fuel,' said his father laconically.

'Oh!'

'One more thing,' said the old man. 'I am perfectly aware that people believe there is still an Earth,

despite my predic-tion, and that I am the subject of bitter criticism in this area. I thought this over years

ago, and I decided it is better for me to suffer a loss of pride than to argue with them. Reason: my

authority derives from Earth. If people actually came to believe that Earth had indeed been destroyed,

then all of us in power - me, you, and the other officers - would no longer be able to do what I did

tonight: remind dissidents what Earth does to those who disobey its mandate.'

The youth was nodding. He felt reluctant to discuss this particular subject, and so it was time to end the

conversation. Therewas another question in his mind, having to do with the relationship of the older

Lesbee with Tellier's widow since his mother's death. But a moment's consideration convinced him that

such an inquiry was not in order.

'Thanks, Dad,' he said, and walked on to his room.

4

For weeks they had been slowing down. And, day by day, the bright stars in the blackness ahead grew

larger and more dazzl-ing. The four suns of Alpha Centauri no longer looked like one brilliant diamond,

but were distinct units separated by notice-able gaps of black space.

They passed Proxima Centauri at a distance of over two billion miles. The faint red star slowly retreated

behind them.

Not Proxima the red, the small, but Alpha A was their first destination. From far Earth itself, the shadow

telescopes had picked out seven planets revolving around A. Surely, of seven planets, one would be

habitable.

When the ship was still four billion miles from the main system, Lesbee II's six-year-old son came to him

in the hydro-ponic gardens - where he had been called to settle a discussion on the uses of solid state

coolants in growing vegetables and fruit.

'Grandfather wants to see you, Dad, in the captain's cabin.'

Lesbee nodded, and noted that the boy ignored the workers in the gardens. He felt vaguely pleased. It

was well for people to realize their station in life. And, ever since the boy's birth, several years after the

crisis created by Ganarette, he had con-sciously striven to instill the proper awareness into the

young-ster.

The boy would grow up with that attitude of superiority so necessary to a commander.

Lesbee forgot that. He tugged the youngster along to the playground adjoining the residential section,

then took an elevator to the officers' deck. His father, four physicists from the engineering department,

and Mr. Carson, Mr. Henwick, and Mr. Browne were in conference as he entered. Lesbee sank quietly

into a chair at the outer edge of the group, but he knew better than to ask questions.

It didn't take long to realize what was going on. The sparks. For days the ship had been moving along

through what seemed to be a violent electric storm. The sparks spattered the outer hull from stem to

stern. On the transparent bridge it had be-come necessary to wear dark glasses; the incessant firefly-like

flares of light upset the muscular balance of the eyes, and caused strain and headache.

The manifestation was getting worse, not better.

'In my opinion,' said the chief physicist, Mr. Plauck, 'we have run into a gas cloud - as you know, space

is not a total vacuum, but is occupied, particularly in and near star systems, by large numbers of free

atoms and electrons. In such a com-plicated structure as is created by the Alpha A, B, C, and Proxima

suns, gravity pull would draw enormous masses of gas atoms from the outer atmospheres of all the stars,

and these would permeate all the surrounding space. As for the electrical aspects, apparently a

disturbance, a flow, has been set up in these gas clouds, possibly even caused by our own passage,

though that is unlikely. Interstellar electrical storms are not new.'

He paused and glanced at one of his assistants question-ingly. The man, a mousy individual named

Kesser, said:

'It happens that I'm in disagreement with the electrical-storm theory, though I also agree on the presence

of masses of gas. After all, that's old stuff in astronomy. But now - my explanation for the sparks. As long

ago as the twentieth cen-tury, perhaps even earlier, it was theorized that the gas mole-cules and atoms

floating in space readily interchanged velocity for heat or heat for velocity. The temperatures of these free

particles, when such an interchange occurred, was found to be as high as twenty thousand degrees

Fahrenheit.'

He looked around, momentarily very unmouselike. 'What would happen if a molecule traveling at such

speed struck our ship? Sparks of heat, of course.' He paused. He was a graying man with a hesitant way

of speaking. 'And then, of course, we must always remember the first Centaurus expedition and be

doubly careful.'

There was a chilled silence. It was strange but Lesbee II had the impression that, although everybody

had been thinking of the first expedition, nobody wanted it mentioned.

Lesbee II glanced at his father. Captain Lesbee was frown-ing. The commander had grown more spare

with years, but his six feet three inches still supported 175 pounds of bone and flesh. He said:

'It is taken for granted that we shall be cautious. One of the purposes of this voyage is to discover the

fate of the first ex-pedition.' His gaze flashed toward the group of physicists. 'As you know,' he said, 'that

expedition set out for Alpha Centauri nearly seventy-five years ago. We are assuming that the en-gines

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

RogueShip ByA.E.VanVogt GranadaPublishingLimitedPublishedin1975byPantherBooksLtdFrogmore,StAlbans,HertsAL22NF FirstpublishedinGreatBritainbyDobsonBooksLtd1967'CentaurusII'wasoriginallypublishedinAstoundingScienceFiction(nowANALOGScienceFact–ScienceFiction),'RogueShip'wasoriginallypublishedinSu...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:121 页

大小:342.55KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-24

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394