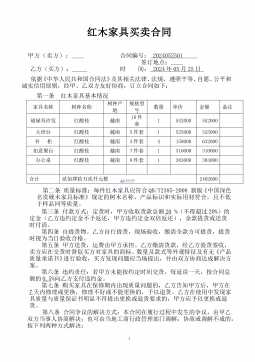

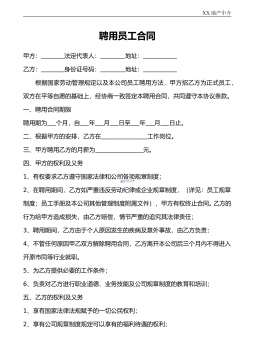

Robin McKinley - Damar 2 - The Hero and the Crown

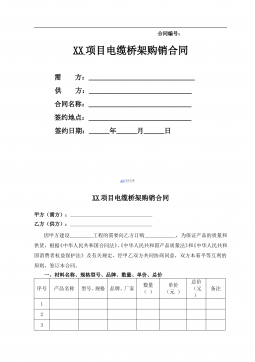

VIP免费

2024-12-20

2

0

892.15KB

105 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

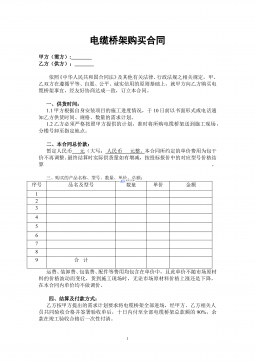

The Hero And The Crown

Damar, Book 2

Robin McKinley

1984

v2. Lots of scanning errors corrected. Spell-checked.

To Terri

The Hero and the Crown takes place some considerable span of years before the time of The Blue

Sword. There are a few fairly dramatic topographical differences between the Damar of Aerin’s day and

that of Harry’s.

Chapter 1

SHE COULD NOT REMEMBER a time when she had not known the story; she had grown up

knowing it. She supposed someone must have told her it, sometime, but she could not remember the

telling. She was beyond having to blink back tears when she thought of those things the story explained,

but when she was feeling smaller and shabbier than usual in the large vivid City high in the Damarian Hills

she still found herself brooding about them; and brooding sometimes brought on a tight headachy feeling

around her temples, a feeling like suppressed tears.

She brooded, looking out over the wide low sill of the stone window-frame; she looked up, into the

Hills, because the glassy surface of the courtyard was too bright at midday to stare at long. Her mind ran

down an old familiar track: Who might have told her the story? It wouldn’t have been her father who told

her, for he had rarely spoken more than a few words together to her when she was younger; his slow

kind smiles and slightly preoccupied air had been the most she knew of him. She had always known that

he was fond of her, which was something; but she had only recently begun to come into focus for him,

and that, as he had told her himself, in an unexpected fashion. He had the best—the only—right to have

told her the story of her birth, but he would not have done so.

Nor would it have been the hafor, the folk of the household; they were polite to her always, in their

wary way, and reserved, and spoke to her only about household details. It surprised her that they still

remembered to be wary, for she had long since proven that she possessed nothing to be wary about.

Royal children were usually somewhat alarming to be in daily contact with, for their Gifts often erupted in

abrupt and unexpected ways. It was a little surprising, even, that the hafor still bothered to treat her with

respect, for the fact that she was her father’s daughter was supported by nothing but the fact that her

father’s wife had borne her. But then, for all that was said about her mother, no one ever suggested that

she was not an honest wife.

And she would not have run and told tales on any of the hafor who slighted her, as Galanna

would—and regularly did, even though everyone treated her with the greatest deference humanly

possible. Galanna’s Gift, it was dryly said, was to be impossible to please. But perhaps from the hafor’s

viewpoint it was not worth the risk to discover any points of similarity or dissimilarity between herself and

Galanna; and a life of service in a household that included Galanna doubtless rendered anyone who

withstood it automatically wary and respectful of anything that moved. She smiled. She could see the

wind stir the treetops, for the surface of the Hills seemed to ripple beneath the blue sky; the breeze, when

it slid through her window, smelled of leaves.

It might very well have been Galanna who told her the story, come to that. It would be like her; and

Galanna had always hated her—still did, for all that she was grown now, and married besides, to Perlith,

who was a second sola of Damar. The only higher ranks were first sola and king; but Galanna had hoped

to marry Tor, who was first sola and would someday be king. It was no matter that Tor would not have

had Galanna if she had been the only royal maiden available—”I’d run off into the Hills and be a bandit

first,” a much younger Tor had told his very young cousin, who had gone off in fits of giggles at the idea

of Tor wearing rags and a blue headband and dancing for luck under each quarter of the moon. Tor, who

at the time had been stiff with terror at Galanna’s very determined attempts to ensnare him, had relaxed

enough to grin and tell her she had no proper respect and was a shameless hoyden. “Yes,” she said

unrepentantly. Tor, for whatever reasons, was rather over-formal with everyone but her; but being first

sola to a solemn, twice-widowed king of a land with a shadow over it might have had that effect on a far

more frivolous young man than Tor. She suspected that he was as grateful for her existence as she was

for his; one of her earliest memories was riding in a baby-sack over Tor’s shoulders while he galloped his

horse over a series of hurdles; she had screamed with delight and wound her tiny hands in his thick black

hair. Teka, later, had been furious; but Tor, who usually took any accusation of the slightest dereliction of

duty with white lips and a set face, had only laughed.

But whenever she decided that it must have been Galanna who first told her the story, she found she

couldn’t believe it of her after all. Having told it for spite and malice, yes; but the story itself had too much

sad grandeur. But perhaps she only felt that way because it was about her mother; perhaps she had

changed it in her own mind, made a tragedy of nothing but sour gossip. But that Galanna would

deliberately spend enough time in her company to tell her the story was out of character; Galanna

preferred whenever possible to look vaguely over the head of the least of her cousins, with an expression

on her face indicating that there was a dead fly on the windowsill and why hadn’t the hafor swept it

away? When Galanna was startled into speaking to her at all, it was usually from a motive of immediate

vengeance. The tale of Arlbeth’s second wife would be too roundabout for her purposes. Still, that it had

been one of the cousins was the best guess. Not Tor, of course. One of the others.

She leaned out of the window and looked down. It was hard to recognize people from the tops of

their heads, several stories up. Except Tor; she always knew him, even if all she had to go on was an

elbow extending an inch or two beyond a doorframe. This below her now was probably Perlith: that

self-satisfied walk was distinctive even from above, and the way three of the hafor, dressed in fine livery,

trailed behind him for no purpose but to lend to their master’s importance by their presence pretty well

assured it. Tor went about alone, when he could; he told her, grimly, that he had enough of company

during the course of his duties as first sola, and the last thing he wanted was an unofficial entourage for

any gaps in the official ones. And she’d like to see her father pulling velvet-covered flunkeys in his wake,

like a child with a toy on a string.

Perlith’s head spoke to another dark head, the hafor waiting respectfully several arms1 length distant;

then someone on a horse—she could not distinguish voices but she heard the click of hoofs—emerged

from around a corner. The rider wore the livery of a messenger, and the cut of his saddle said he came

from the west. Both heads turned toward him and tipped up, so she could see the pale blur of their faces

as they spoke to him. Then the horseman cantered off, the horse placing its feet very delicately, for it was

dangerous to go too quickly across the courtyard; and Perlith and the other man, and Perlith’s entourage,

disappeared from her view.

She didn’t have to hear what they said to each other to know what was going on; but the knowledge

gave her no pleasure, for it had already brought her both shame and bitter disappointment. It was either

the shame or the disappointment that kept her mewed up in her rooms, alone, now.

She had hardly seen her father or Tor for the week past as they wrestled with messages and

messengers, as they tried to slow down whatever it was that would happen anyway, while they tried to

decide what to do when it had happened. The western barons—the fourth solas—were making trouble.

The rumor was that someone from the North, either human or human enough to look it, had carried a bit

of demon-mischief south across the Border and let it loose at the barons’ council in the spring. Nyrlol

was the chief of the council for no better reason than that his father had been chief; but his father had

been a better and a wiser man. Nyrlol was not known for intelligence, and he was known for a short and

violent temper: the perfect target for demon-mischief.

Nyrlol’s father would have recognized it for what it was. But Nyrlol had not recognized anything; it

had simply seemed like a wonderful idea to secede from Damar and the rule of Damar’s King Arlbeth

and Tor-sola, and set himself up as King Nyrlol; and to slap a new tax on his farmers to support the

raising of an army, eventually to take the rest of Damar away from Arlbeth and Tor, who didn’t run it as

well as he could. He managed to convince several of his fellow barons (demon-mischief, once it has

infected one human being, will usually then spread like a plague) of the brilliance of his plan, while the

mischief muddled their wits. There had been a further rumor, much fainter, that Nyrlol had, with his

wonderful idea, suddenly developed a mesmerizing ability to sway those who heard him speak; and this

rumor was a much more worrying one, for, if true, the demon-mischief was very strong indeed.

Arlbeth had chosen to pay no attention to the second rumor; or rather to pay only enough attention to

it to discount it, that none of his folk might think he shunned it from fear. But he did declare that the

trouble was enough that he must attend to it personally; and with him would go Tor, and a substantial

portion of the army, and almost as substantial a portion of the court, with all its velvets and jewels

brought along for a fine grand show of courtesy, to pretend to disguise the army at its back. But both

sides would know that the army was an army, and the show only a show. What Arlbeth planned to do

was both difficult and dangerous, for he wished to prevent a civil war, not provoke one. He would

choose those to go with him with the greatest care and caution.

“But you’re taking Perlith?” she’d asked Tor disbelievingly, when she met him by chance one day,

out behind the barns, where she could let her disbelief show.

Tor grimaced. “I know Perlith isn’t a very worthwhile human being, but he’s actually pretty effective

at this sort of thing—because he’s such a good liar, you know, and because he can say the most

appalling things in the most gracious manner.”

No women rode in Arlbeth’s army. A few of the bolder wives might be permitted to go with their

husbands, those who could ride and had been trained in cavalry drill; and those who could be trusted to

smile even at Nyrlol (depending on how the negotiations went), and curtsy to him as befitted his rank as

fourth sola, and even dance with him if he should ask. But it was expected that no wife would go unless

her husband asked her, and no husband would ask unless he had asked the king first.

Galanna would certainly not go, even if Perlith had been willing to go to the trouble of obtaining leave

from Arlbeth (which would probably not have been granted). Fortunately for the peace of all concerned,

Galanna had no interest in going; anything resembling hardship did not appeal to her in the least, and she

was sure that nothing in the barbaric west could possibly be worth her time and beauty.

A king’s daughter might go too; a king’s daughter who had, perhaps, proved herself in some small

ways; who had learned to keep her mouth shut, and to smile on cue; a king’s daughter who happened to

be the king’s only child. She had known they would not let her; she had known that Arlbeth would not

dare give his permission even had he wanted to, and she did not know if he had wanted to. But he could

not dare take the witch woman’s daughter to confront the workings of demon-mischief; his people would

never let him, and he too sorely needed his people’s good will.

But she could not help asking—any more, she supposed, than poor stupid Nyrlol could help going

mad when the demon-mischief bit him. She had tried to choose her time, but her father and Tor had been

so busy lately that she had had to watt, and wait again, till her time was almost gone. After dinner last

night she had finally asked; and she had come up here to her rooms afterward and had not come out

again.

“Father.” Her voice had gone high on her, as it would do when she was afraid. The other women,

and the lesser court members, had already left the long hall; Arlbeth and Tor and a few of the cousins,

Perlith among them, were preparing for another weary evening of discussion on Nyrlol’s folly. They

paused and all of them turned and looked at her, and she wished there were not so many of them. She

swallowed. She had decided against asking her father late, in his own rooms, where she could be sure to

find him alone, because she was afraid he would only be kind to her and not take her seriously. If she

was to be shamed—and she knew, or she told herself she knew, that she would be refused—at least let

him see how much it meant to her, that she should ask and be refused with others looking on.

Arlbeth turned to her with his slow smile, but it was slower and less of it reached his eyes than usual.

He did not say, “Be quick, I am busy,” as he might have done—and small blame to him if he had, she

thought forlornly.

“You ride west—soon? To treat with Nyrlol?” She could feel Tor’s eyes on her, but she kept her

own eyes fixed on her father.

“Treat?” said her father. “If we go, we go with an army to witness the treaty.” A little of the smile

crept into his eyes after all. “You are picking up courtly language, my dear. Yes, we go to ‘treat’ with

Nyrlol.”

Tor said: “We have some hope of catching the mischief-one did not say demon aloud if one could

help it—”and bottling it up, and sending it back where it came from. Even now we have that hope. It

won’t stop the trouble, but it will stop it getting worse. If Nyrlol isn’t being pricked and pinched by it, he

may subside into the subtle and charming Nyrlol we all know and revere.” Tor’s mouth twisted up into a

wry smile.

She looked at him and her own mouth twitched at the corners. It was like Tor to answer her as if she

were a real part of the court, even a member of the official deliberations, instead of an interruption and a

disturbance. Tor might even have let her go with them; he wasn’t old enough yet to care so much for his

people’s good opinion as Arlbeth did; and furthermore, Tor was stubborn. But it was not Tor’s decision.

She turned back to her father.

“When you go—may I come with you?” Her voice was little more than a squeak, and she wished she

were near a wall or a door she could lean on, instead of in the great empty middle of the dining-hall, with

her knees trying to fold up under her like an hour-old foal’s.

The silence went suddenly tight, and the men she faced went rigid: or Arlbeth did, and those behind

him, for she kept her face resolutely away from Tor. She thought that she could not bear it if her one loyal

friend forsook her too; and she had never tried to discover the extent of Tor’s stubbornness. Then the

silence was broken by Perlith’s high-pitched laughter.

“Well, and what did you expect from letting her go as she would these last years? It’s all very well to

have her occupied and out from underfoot, but you should have thought the price you paid to be rid of

her might prove a little high. What did you expect when our honored first sola gives her lessons in

swordplay and she tears around on that three-legged horse like a peasant boy from the Hills, with never a

gainsay but a scold from that old shrew that serves as her maid? Might you not have thought of the

reckoning to come? She needed slaps, not encouragement, years ago—she needs a few slaps now, I

think. Perhaps it is not too late.”

“Enough.” Tor’s voice, a growl.

Her legs were trembling now so badly that she had to move her feet, shuffle in her place, to keep the

joints locked to hold her up. She felt the blood mounting to her face at Perlith’s words, but she would not

let him drive her away without an answer. “Father?”

“Father,” mimicked Perlith. “It’s true a king’s daughter might be of some use in facing what the North

has sent us; a king’s daughter who had true royal blood in her veins ....”

Arlbeth, in a very unkinglike manner, reached out and grabbed Tor before anyone found out what the

first sola’s sudden move in Perlith’s direction might result in. “Perlith, you betray the honor of the second

sola’s place in speaking thus.”

Tor said in a strangled voice, “He will apologize, or I’ll give him a lesson in swordplay he will not like

at all.”

“Tor, don’t be a—” she began, outraged, but the king’s voice cut across hers. “Perlith, there is

justice in the first sola’s demand.”

There was a long pause while she hated everyone impartially: Tor for behaving like a farmer’s son

whose pet chicken has just been insulted; her father, for being so immovably kingly; and Perlith for being

Perlith. This was even worse than she had anticipated; at this point she would be grateful just for escape,

but it was too late.

Perlith said at last, “I apologize, Aerin-sol. For speaking the truth,” he added venomously, and turned

on his heel and strode across the hall. At the doorway he paused and turned to shout back at them: “Go

slay a dragon, lady! Lady Aerin, Dragon-Killer!”

The silence resettled itself about them, and she could no longer even raise her eyes to her father’s

face.

“Aerin—” Arlbeth began.

The gentleness of his voice told her all she needed to know, and she turned away and walked toward

the other end of the hall, opposite the door which Perlith had taken. She was conscious of the length of

the way she had to take because Perlith had taken the shorter way, and she hated him all the more for it;

she was conscious of all the eyes on her, and conscious of the fact that her legs still trembled, and that the

line she walked was not a straight one. Her father did not call her back. Neither did Tor. As she reached

the doorway at last, Perlith’s words still rang in her ears: “A king’s daughter who had true royal blood in

her veins ... Lady Aerin, Dragon-Killer.” It was as though his words were hunting dogs who tracked her

and nipped at her heels.

Chapter 2

HER HEAD ACHED. The scene was still so vividly before her that the door of her bedroom was

half open before she heard it. She spun round, but it was only Teka, bearing a tray; Teka glanced once at

her scowling face and averted her eyes. She was probably first chosen for my maid for her skill at

averting her eyes, Aerin thought sourly; but then she noticed the tray, and the smell of the steam that rose

from it, and the worried mark between Teka’s eyebrows. Her own face softened.

“You can’t not eat,” Teka said.

“I hadn’t thought about it,” Aerin replied, realizing this was true.

“You shouldn’t sulk,” Teka then said, “and forget about eating.” She looked sharply at her young

charge, and the worried mark deepened.

“Sulking,” said Aerin stiffly.

Teka sighed. “Hiding. Brooding. Whatever you like. It’s not good for you.”

“Or for you,” Aerin suggested.

A smile touched the corners of the worry. “Or for me.”

“I will try to sulk less if you will try to worry less.”

Teka set the tray down on a table and began lifting napkins off of plates. “Talat missed you today.”

“He told you so, of course.” Teka’s fear of anything larger than the smallest pony, and therefore the

fact that she gave a very wide berth to the stables and pastures beyond them, was well known to Aerin.

“I’ll go down after dark.” She turned back to the window. There were more comings and goings across

the stretch of courtyard that her bedroom overlooked; she saw more messengers, and two men racing by

on foot in the uniform of the king’s army, with the red divisional slash on their left forearms which meant

they were members of the supply corps. Equipping the king’s company for its march west was

proceeding at a pace presently headlong and increasing toward panicky. Under normal circumstances

Aerin saw no one from her bedroom window but the occasional idling courtier.

Something on the tray rattled abruptly, and there was a sigh. “Aerin—”

“Whatever you’re going to say I’ve thought of already,” Aerin said without turning around.

Silence. Aerin finally looked round at Teka, standing with head and shoulders bowed, staring at the

tray. The plates were heavy earthenware, handsome and elegant, but easily replaced if Aerin managed to

break one, as she often did; and she had not the small Gift to mend them. She stared at the plates. Tor

had mended her breakages when she was a baby, but she was too proud to ask now she was far past

the age when she should have been able to fit the bits together, glower at them with the curious royal

Gifted look, and have them grow whole again. It did not now help her peace of mind or her temper either

that she had been an unusually large and awkward child who seemed able to break things simply by

being in the same room with them; as if fate, having denied her something that should have been her

birthright, wanted her never to forget it. Aerin was not a particularly clumsy young woman, but she was

by now so convinced of her lack of coordination that she still broke things occasionally out of sheer

dread.

Teka had silently exchanged the finer royal plates for these earthenware ones several years ago, after

Galanna had found out that the red-and-gold ones that should only be used by members of the first circle

of the royal house—which included Aerin—were slowly disappearing. She had one of her notorious

temper tantrums over this, caused crisis and dismay in the whole hierarchy of the hafor, and turned off

three of the newest and lowliest servant girls on suspicion of stealing—and then, when no one could

possibly overlook the commotion she was making, contrived to discover that the disappearances were

merely the result of Aerin being clumsy. “You revolting child,” she said to a mutinous Aerin; “even if you

are incapable”—there was inexpressible malice lurking behind the word—”of mending the settings

yourself, you might save the pieces and let one of us do it for you.”

“I’d hang myself first,” spat Aerin, “and then I’d come back and haunt you till you were haggard with

fear and lost all your looks and people pointed at you in the streets—”

At this point Galanna slapped her, which was a tactical error. In the first place, it needed only such an

excuse for Aerin to jump on her and roll her over on the floor, bruise one eye, and rip most of the lace off

her extremely ornate afternoon dress—somehow both the court members and the hafor witness to this

scene were a little slow in dragging Aerin off her—and in the second place, both the slap and its result

quite ruined Galanna’s attempted role of great lady dealing with contemptible urchin. It was generally

considered—Galanna was no favorite—that Aerin had won that round. Of the three serving girls, one

was taken back, one was given a job in the stables, which she much preferred, and one, declaring that

she wouldn’t have any more to do with the royal house if saying so got her beheaded for treason, went

home to her own village, far from the City.

Aerin sighed. Life had been easier when her ultimate goal had been murdering Galanna with her bare

hands. She had continued to use the finer ware when she ate with the court, of course; when she was

younger she had rarely been compelled to do so, fortunately, since she never got much to eat, but sat

rigidly and on her guard (Galanna’s basilisk glare from farther down the high table helped) for the entire

evening. But at least she didn’t break anything either, and Teka could always be persuaded to bring her a

late supper as necessary. On earthenware plates.

She lifted her eyes to Teka, who was still standing motionless behind the tray. “Teka, I’m sorry I’m

so tiresome. I can’t seem to help it. It’s in my blood, like being clumsy is—like everything else isn’t.” She

walked over and gave the older woman a hug, and Teka looked up and half smiled.

“I hate to see you ... fighting everything so.”

Aerin’s eyes rose involuntarily to the old plain sword hanging at the head of her tall curtained bed.

“You know Perlith and Galanna are horrid because they’re horrid themselves—”

“Yes,” said Aerin slowly. “And because I’m the only daughter of the witchwoman who enspelled the

king into marrying her, and I’m such a desperately easy butt. Teka,” she said before the other had a

chance to break in, “do you suppose it was Galanna who first told me that story? I’ve been trying to

remember when I first heard it.’’

“Story?” said Teka, carefully neutral. She was always carefully neutral about Aerin’s mother, which

was one of the reasons Aerin kept asking about her. ‘ “Yes. That my mother enspelled my father to get

an heir that would rule Damar, and that she turned her face to the wall and died of despair when she

found she had borne a daughter instead of a son, since they usually find a way to avoid letting daughters

inherit.”

Teka shook her head impatiently.

“She did die, “Aerin said.

“Women die in childbed.”

“Not witches, often.”

“She was not a witch.”

Aerin sighed, and looked at her big hands, striped with callus and scarred with old blisters from

sword and shield and pulling her way through the forest tangles after her dragons—Dragon-Killer—and

from falling off the faithful Talat. “You would certainly think she wasn’t from the way her daughter goes

on. If he was going to turn out like me, it wouldn’t have done my poor mother any good to have had a

son.” She paused, brooding over her last burn scar, where a dragon had licked her and the ointment

hadn’t gone on quite evenly. “What was my mother like?”

Teka looked thoughtful. She too looked toward Aerin’s sword and dragon spears, but Aerin was

pretty sure she did not see them, for Teka did not approve of her first sol’s avocation. “She was much

like you but smaller—frail almost.” Her shoulders lifted. “Too frail to bear a child. And yet it was rather

as though something was eating her from the inside; there was a fire behind that pale skin, always burning.

I think she knew she had only a little time and she was fighting for enough time to bear her baby.” Teka’s

eyes refocused on the room, and she looked hastily away from the dragon spears. “You were a fine

strong child from the first.”

“Do you think she enspelled my father?”

Teka looked at her, frowning. “Why do you ask so silly a question?”

“I like to hear you tell stories.”

Teka laughed involuntarily. “Well. No, I don’t think she enspelled your father—not the way Galanna

and her lot mean, anyway. She fell in love with him, and he with her; that’s a spell if you like.”

They had had this conversation before; many times since Aerin was old enough to talk and ask

questions. But over the years Teka sometimes let fall one more phrase, one more adjective, as Aerin

asked the same questions, and so Aerin kept on asking. That there was a mystery she had no doubt. Her

father wouldn’t discuss her mother with her at all, beyond telling her that he still missed her, which Aerin

did find reassuring as far as it went. But whether the truth behind the mystery was known to everyone but

her and was too terrible to speak of, particularly to the mystery’s daughter, or whether it was a mystery

that no one knew and therefore everyone blamed her for endlessly reminding them of, she had never

been able to make up her mind. On the whole she inclined to the latter; she couldn’t imagine anything so

awful that Galanna would recoil from using it against her. And if there were something quite that awful,

then Perlith wouldn’t be able to resist ceasing to ignore her long enough to explain it.

Teka had turned back to the tray and poured a cup of hot malak, and handed it to Aerin, who settled

down cross-legged on her bed, the hanging scabbard just brushing the back of her neck. “I brought

mik-bars too, for Talat, so you need not go to the kitchens if you don’t wish to.”

Aerin laughed. “You know me too well. After sulking, I sneak off to the stables after

dark—preferably after bedtime—and talk to my horse.”

Teka smiled and sat down on the red-and-blue embroidered cushion (her embroidery, not Aerin’s)

on the chair by Aerin’s bed. “I have had much of the raising of you, these long years.”

“Very long years,” agreed Aerin, reaching for a leg of turpi. “Tell me about my mother.”

Teka considered. “She came walking into the City one day. She apparently owned nothing but the

long pale gown she wore; but she was kind, and good with animals, and people liked her.”

“Until the king married her.”

Teka picked up a slab of dark bread and broke it in half. “Some of them liked her even then.”

“Did you?”

“King Arlbeth would never have chosen me to nurse her daughter else.”

“Am I so like her as folk say?”

Teka stared at her, but Aerin felt it was her mother Teka looked at. “You are much like what your

mother might have been had she been well and strong and without hurt. She was no beauty, but she ...

caught the eye. You do too.”

Tor’s eye, thought Aerin, for which Galanna hates me even more enthusiastically than she would

anyway. She is too stupid to recognize the difference between that sort of love and the love of a friend

who depends on the particular friendship—or a farmer’s son’s love for his pet chicken. I wonder if

Perlith hates me because his wife hoped to marry Tor, or merely for small scuttling reasons of his own.

“That’s just the silly orange hair.”

“Not orange. Flame-colored.”

“Fire is orange.”

“You are hopeless.”

Aerin grinned in spite of a large mouthful of bread. “Yes. And besides, it is better to be hopeless,

because—” The grin died.

Teka said anxiously: “My dear, you can’t have believed your father would let you ride in the army.

Few women do so—”

“And they all have husbands, and go only by special dispensation from the king, and only if they can

dance as well as they can ride. And none at all has ridden at the king’s side since Aerinha, goddess of

honor and of flame, first taught men to forge their blades,” Aerin said fiercely. “You’d think Aerinha

would have had better sense. If we were still using slingshots and magic songs, I suppose we’d still all be

riding with them. They needed the women’s voices for the songs to work—”

“That’s only a pretty legend,” said Teka firmly. “If the singing worked, we’d still be using it.”

“Why? Maybe it got lost with the Crown. They might at least have named me Cupka or Marli or—or

Galanna or something. Something to give me fair warning.”

“They named you for your mother.”

“Then she has to have been Damarian,” Aerin said. This was also an old argument. “Aerinha was

Damarian.”

“Aerinha is Damarian,” said Teka, “and Aerinha is a goddess. No one knows where she first came

from.”

There was a silence. Aerin stopped chewing. Then she remembered she was eating, swallowed, and

took another bite of bread and turpi. “No, I don’t suppose I ever thought the king would let his only, and

she somewhat substandard, daughter ride into possible battle, even though sword-handling is about the

only thing she’s ever gotten remotely good at—her dancing is definitely not satisfactory.” She grunted.

“Tor’s a good teacher. He taught me as patiently as if it were normal for a king’s child to have to learn

every sword stroke by rote, to have to practice every maneuver till the muscles themselves know it, for

there is nothing that wakes in this king’s child’s Wood to direct it.” Aerin looked, hot-eyed, at Teka,

remembering again Perlith’s words as he left the hall last night. “Teka, dragons aren’t that easy to kill.”

“I would not want to have to kill one,” Teka said sincerely. Teka, maid and nurse, maker of possets

and sewer of patches, scolder and comforter and friend, who saw nothing handsome in a well-balanced

sword and who always wore long full skirts and aprons.

Aerin burst out laughing. “No, I am not surprised.”

Teka smiled comfortably.

Aerin ate several of the mik-bars herself before dusk fell and she could slip privately out of the castle

by the narrow back staircase that no one else used, and into the largest of the royal barns where the

horses of the first circle were kept. She liked to pretend that the ever observant men and women of the

horse, the sofor, did not notice her every time she crept in at some odd hour to visit Talat. Anyone else of

the royal blood could be sure of not being seen, had they wished to be unseen; Aerin could only tiptoe

through the shadows, when there were shadows, and keep her voice down; and yet she knew she was

simply recognized and permitted to pass. The sofor accepted that when she came thus quietly she wished

to be left alone, and they respected her wishes; and Hornmar, the king’s own groom, was her friend. All

the sofor knew what she had done for Talat, so the fact that they were being kind by ignoring her hurt her

less than similar adaptations to the first sol’s deficiencies did elsewhere in the royal court.

Talat had been wondering what had become of her for almost two days, and she had to feed him the

last three milk-bars before he forgave her; and then he snuffled her all over, partly to make sure she was

not hiding anything else he might eat, partly to make sure she had in fact returned to him. He rubbed his

cheek mournfully along her sleeve and rolled a reproachful eye.

Talat was nearly as old as she was; he had been her father’s horse when she was small. She

remembered the dark grey horse with the shining black dapples on his shoulders and flanks, and the hot

dark eye. The king’s trappings had looked particularly well on him: red reins and cheekpieces, a red skirt

to the saddle, and a wide red breastplate with a gold leaf embroidered on it; the surka leaf, the king’s

emblem, for only one of the royal blood could touch the leaves of the surka plant and not die of its sap.

He was almost white now. All that remained of his youth were a few black hairs in his mane and tail,

and the black tips of his ears.

“You have not been neglected; don’t even try to make me think so. You are fed and watered and let

out to roll in the dirt every day whether I come or not.” She ran a hand down his back; one of Hornmar1

s minions had of course groomed him to a high gloss, but Talat liked to be fussed over, so she fetched

brushes and groomed him again while he stretched his neck and made terrible faces of enjoyment. Aerin

relaxed as she worked, and the memory of the scene in the hall faded, and the mood that had held for the

last two days lightened and began to break up, like clouds before a wind.

Chapter 3

THE YOUNG AERIN had worshipped Talat, her father’s fierce war-stallion, with his fine lofty head

and high tail. She thought it very impressive that he would rear and strike at anyone but Hornmar or her

father, rear with his ears flat back, so that his long wedge-shaped head looked like a striking snake’s.

But when she was twelve years old her father had gone off to a Border battle: a little mob of

Northerners had slipped across the mountains and set fire to a Damarian village. Something of the sort

happened not infrequently, and in those days Arlbeth or his brother Thomar attended to such

occurrences, riding out hopefully and in haste to chop up a few Northerners who had stayed to loot

instead of scrambling back across the Border again at once. The Northerners knew Damarian reprisals

were invariably swift, and yet always there were a few greedy ones who lingered. It was Arlbeth’s turn

this time; and there had been more Northerners than usual. Three men had been killed outright, and one

horse; two men injured—and Talat.

Talat had been slashed across the right flank by a Northern sword, but he had carried Arlbeth safely

through the battle till its end. Arlbeth was appalled when at last he was free to dismount and attend to it;

there were muscles and tendons severed; the horse should have fallen when he took the blow. Arlbeth’s

first thought was to end it then; but he looked at his favorite horse’s face, with the lips curled back from

the teeth and the white showing around the eye: Talat was daring his master to kill him, and his master

couldn’t do it. Arlbeth thought, If he is stubborn enough to walk home on three legs, I am stubborn

enough to let him try.

Aerin had been one of the first to run out of the City and meet the returning company. They were

slow coming home, for Talat had set the pace, and while Aerin knew that if anything had happened to her

father a messenger would have been sent on ahead, still their slowness had worried her—and she felt an

awful fear squeeze her belly when she first saw Talat, his head hanging nearly to his knees, put three legs

slowly down one after the other, and hop for the fourth. She only then saw her father walking on the

horse’s far side.

Somehow Talat climbed the last hill to the castle, and crept into his own stall, and with a terrible sigh,

lay slowly down in the straw there, the first time he had been off his feet since the sword struck him.

“He’s made it this far,” said Arlbeth grimly, and sent for the healers; but when they came to corner Talat

in his stall, he surged to his feet and threatened them, and when they tried to pour a narcotic down his

throat, it took four of the hafor and a chain twisted around his jaw to hold him still.

They sewed the leg up, and it healed. But he was lame, and he would always be lame. They turned

him out into a pasture of his own, green with chest-high grass, cool with trees, with a brook to drink from

and a pond to soak in, mud at the edge of the pond for rolling, and a nice big dry shed for rain; and

Hornmar brought him grain morning and evening, and talked to him.

But Talat only grew thin and began to lose his black dapples; his coat stared and he didn’t eat his

grain, and he turned his back on Hornmar, for Hornmar was taking care of Arlbeth’s new war-horse

now.

Arlbeth had hoped Talat might sire him foals; he would like nothing better than to ride Talat again.

But Talat’s bad leg was too weak; he could not mount the mares, and so he savaged them, and turned on

his handlers when they tried to prevent him. Talat was sent back to his pasture in disgrace. Had he been

any horse but the king’s favorite, he would have been fed to the dogs.

It had been over two years since Arlbeth had led Talat home from his last battle, and Aerin was

fifteen when she ate some leaves from the surka. While they had been trying to breed Talat, Aerin had

been turning corners that weren’t there and falling downstairs and being haunted by purple smoke

billowing from scarlet caves.

It began with a confrontation with Galanna, as so much of Aerin’s worst trouble did. Galanna was the

youngest of the royal cousins, but for Aerin, and she had been about to turn seven when Aerin was born.

Galanna had become quite accustomed to being the baby of the family, petted and indulged; and she was

a very pretty child, and learned readily how best to play up to those likeliest to spoil her. Tor was nearest

her in age, only four years her elder, but he was always trying to pretend that he was just as grown up as

the next lot of cousins, Perlith and Thurny and Greeth, who were six, seven, and ten years older than he

was. Tor was no threat. The next-youngest girl cousin was fifteen years older than Galanna, and she,

poor Katah, was plain. (She was also, very shortly after Aerin’s birth, married off to one of the provincial

barons, where, much to Galanna’s disgust, she thrived and became famous for settling a land dispute in

her husband’s family that had been the cause of a blood feud for generations.)

Galanna was not at all pleased by Aerin’s birth; not only was Aerin a first sol, which Galanna would

never be unless she managed to marry Tor, but her mother died bearing her, which made Aerin

altogether too interesting a figure within the same household that Galanna wished to continue to revolve

around herself.

Aerin was by nature the son of child who got into trouble first and thought about it later if at all, and

Galanna, in her way, was quite clever. Galanna it was who dared her to eat a leaf of the surka; she dared

her by saying that Aerin would be afraid to touch the royal plant, because she was not really of royal

blood: she was a throwback to her mother’s witch breed, and Arlbeth was her father in name only. If she

touched the surka, she would die.

At fifteen Aerin should already have shown signs of her royal blood’s Gift; usually the Gift began to

make its presence known—most often in poltergeist fits—years younger. Galanna had contrived to

disguise her loathing for her littlest cousin for several years after her temper tantrums upon Aerin’s birth

had not been a complete success; but lately had occurred to an older Galanna that if Aerin really was a

throw-back, a sport, as she began to appear truly to be, Galanna had excellent reason to scorn and

dislike her: her existence was a disgrace to the royal honor.

They made a pair, facing off, standing alone in the royal garden, glaring at each other. Galanna had

come to her full growth and beauty by that time: her blue-black hair hung past her hips in heavy waves,

and was artfully held in place by a golden webwork of fine thread strung with pearls; her cheeks were

flushed becomingly with rage till they were as red as her lips, and her huge black eyes were opened their

widest. Her long eyelashes had almost grown back since the night Aerin had drugged her supper wine

and crept into her bedroom later and cut them off. Everyone had known at once who had done it, and

Aerin, who in general held lying in contempt, had not bothered to deny it. She had said before the

gathered court—for Galanna, as usual, had insisted on a public prosecution—that Galanna should have

been grateful she hadn’t shaved her head for her; she’d been snoring like a pig and wouldn’t have

wakened if she’d been thrown out her bedroom window. Whereupon Galanna had gone off in a fit of

strong hysterics and had to be carried from the hall (she’d been wearing a half-veil that covered her face

to her lips, that no one might see her ravaged features), and Aerin had been banished to her private

rooms for a fortnight.

Aerin was as tall as Galanna already, for Galanna was small and round and compact, and Aerin was

gangly and awkward; and Aerin’s pale skin came out in splotches when she was angry, and her fiercely

curly hair—which when wet from the bath was actually longer than Galanna’s—curled all the more

fiercely in the heat of her temper, and for all the pins that attempted to keep it under control. They were

alone in the garden; and whatever happened Galanna had no fear that Aerin would ever tale-bear (which

was another excellent reason for Galanna to despise her), so when Aerin spun around, pulled half a

branch off the surka, and stuffed most of it into her mouth, Galanna only smiled. Her full lips curved most

charmingly when she smiled, and it brought her high cheekbones into delicate prominence.

Aerin gagged, gasped, turned a series of peculiar colors which ended with grey, and fell heavily to the

ground. Cabana noticed that she was still breathing, and therefore waited a few minutes while Aerin

twitched and shook, and then went composedly to find help. Her story was that she had gone for a walk

in the garden and found Aerin there. This, so far as it went, was true; but she had been planning to find

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

TheHeroAndTheCrownDamar,Book2RobinMcKinley1984 v2.Lotsofscanningerrorscorrected.Spell-checked. ToTerri TheHeroandtheCrowntakesplacesomeconsiderablespanofyearsbeforethetimeofTheBlueSword.ThereareafewfairlydramatictopographicaldifferencesbetweentheDamarofAerin’sdayandthatofHarry’s.Chapter1SHECOULDNO...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:105 页

大小:892.15KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-20

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394