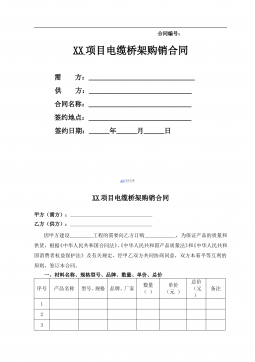

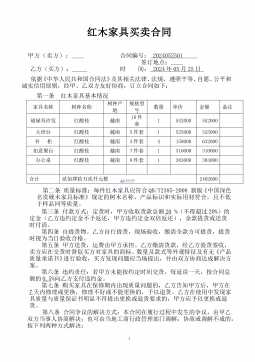

Who Killed Kennedy

VIP免费

2024-12-05

1

0

1.63MB

156 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

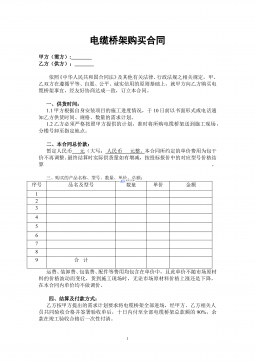

WHO KILLED

KENNEDY

WHO KILLED

KENNEDY

The shocking secret linking a Time

Lord and a President

David Bishop & James Stevens

First published in Great Britain in 1996 by

Doctor Who Books

an imprint of Virgin Publishing Ltd

332 Ladbroke Grove

London W10 5AH

Copyright © David Bishop 1996

The right of David Bishop to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

'Doctor Who' series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1996

ISBN 0 426 20467 0

Typeset by Galleon Typesetting, Ipswich

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Mackays of Chatham PLC

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead,

is purely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior written consent in any form

of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Scanned by The Camel

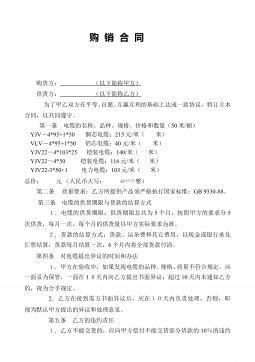

Who Killed Kennedy: The shocking secret linking a

Time Lord and a President

PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................ 6

PART ONE: BAD SCIENCE ................................................................................................................. 13

One ........................................................................................................................................................... 14

Two ........................................................................................................................................................... 22

Three ........................................................................................................................................................ 31

Four .......................................................................................................................................................... 38

Five ........................................................................................................................................................... 44

PART TWO: MASTERMIND ................................................................................................................. 55

Six ............................................................................................................................................................ 56

Seven ....................................................................................................................................................... 57

Eight ......................................................................................................................................................... 60

Nine .......................................................................................................................................................... 61

Ten ........................................................................................................................................................... 68

Eleven ...................................................................................................................................................... 70

Twelve ...................................................................................................................................................... 78

Thirteen .................................................................................................................................................... 80

Fourteen ................................................................................................................................................... 88

Fifteen ...................................................................................................................................................... 92

Sixteen ..................................................................................................................................................... 93

Seventeen ................................................................................................................................................ 99

Eighteen ................................................................................................................................................... 100

Nineteen ................................................................................................................................................... 109

Twenty ...................................................................................................................................................... 118

Twenty-One .............................................................................................................................................. 119

PART THREE: WHO KILLED KENNEDY ............................................................................................. 125

Twenty-Two .............................................................................................................................................. 126

Twenty-Three ........................................................................................................................................... 129

Twenty-Four ............................................................................................................................................. 134

EPILOGUE ............................................................................................................................................... 136

Acknowledgements, etc: The Real Author Speaks . . . ........................................................................... 139

Writer's Commentary ............................................................................................................................... 144

PREFACE

We will not prematurely, or unnecessarily, pursue the cause of worldwide nuclear

war, in which even the fruits of victory would be ashes in our mouths.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy

22 January 1964, Washington DC, USA

President John Fitzgerald Kennedy stared at the hastily typed-out memo. It was difficult to read

the words, his hands were shaking so much. The syntax was garbled, at least two words had

letters transposed, and the type was smeared with what seemed to be tears. Despite all this, the

message contained on the single page of yellow paper was plain – the world stood on the brink of

nuclear war.

Tens of thousands of troops were massing in East Germany ready to surge across Europe

towards Great Britain. West Berlin had already fallen to the communist forces. In Eurasia, China

was threatening to retaliate with a nuclear strike on Moscow unless Soviet troops withdrew in the

next 72 hours from disputed border regions. The world's superpowers were at each other's throats

and the United States of America was in the middle, its efforts to negotiate a truce frustrated and

impotent.

For three days and nights the President, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and their advisers had been

working without remission to prevent this moment arriving. Sleep was rare, taken in snatches;

food was merely an afterthought when the pangs of hunger became too debilitating to ignore;

families were forgotten as this handful of men and women tried to find some way forward, some

way out of this crisis.

Throughout it all, the President had remained in the Oval Office, calling each of the world

leaders personally, desperately trying to talk sense into the key players. He had thought that if he

spoke to them as one human being to another, then maybe the situation could be resolved.

Instead the crisis had only deepened.

John F Kennedy swayed slowly back and forth in his beloved wooden rocking chair, looking to

his younger brother as he asked a question. 'Jesus Christ, Bobby, are these figures accurate?'

The Attorney General nodded grimly, his face ashen. 'We could be at war any minute, Jack.'

The President crumpled the document in his left hand while the fingers of his right hand lightly

touched the wound in his neck. It was still sore and stubbornly refused to heal, a constant

reminder of the attempt on his life in Dallas, Texas, just two months before.

The assassin had been unsuccessful in his bid to kill Kennedy, but the attempt itself had

triggered this greater crisis. The gunman killed several Dallas police officers before turning his rifle

on himself. Beneath his street clothes the assassin wore the uniform of a Russian soldier. Of

course the Russians had denied any involvement or knowledge of the attempt to kill the President

of the United States, but no one believed them.

Since then, international tension had escalated at an alarming rate. Now the world was within

minutes of destroying itself in a nuclear conflict no one could ever win – a holocaust of light and

fury and radiation. Sometimes John Fitzgerald Kennedy wished the assassin had been successful –

had killed him and escaped. Then maybe none of this would have happened.

'Doesn't Khrushchev understand that I can't back down? Didn't he learn anything from Cuba?'

The President pulled himself out of the rocking chair and began to pace the Oval Office. A camp

bed had been set up to one side of the room for him to grab a few hours sleep. That would not be

needed now. John F. Kennedy breathed deeply and coughed on the blue haze of tobacco smoke

hanging in the air. Worse than the smell of old tobacco and stale sweat was the stench of despair,

clinging to everyone and everything in the Oval Office.

The President stopped to rest a weary hand on his brother's shoulder. Never a heavy sleeper

because of his chronic back problems, the crisis of the past days had left John F. Kennedy hardly a

moment's rest. His gaze settled on the faces of two smiling infants in a framed photograph

standing on his desk. 'Bobby, if the worst happens, are the children safe?'

His brother managed a smile. 'Yes. The families of all the White House staff and senior

Government members are already down in the shelter. John junior's been asking after you,

wanting to know when you'll join him and Caroline.'

'God knows what sort of world they'll have left to grow up in if –'

'Mr President!'

All faces turned to the doorway as the Secretary of Defense, Robert McNamara, burst into the

room. 'Sir, we've got confirmation of missile launch. The birds are in the sky!'

'How many?' asked the President, hoping against hope it was a rogue attack – something that

could be sustained without retaliation. Anything to avoid full-scale war.

'Dozens of war birds already, maybe hundreds,' replied McNamara, tears in his eyes.

'Continental Army Command estimate four minutes to the first impact.'

The President sagged, his last reserves of willpower and strength leaving him. His brother led

him over to the desk that had served so many presidents in times of crisis, but never one so

grave as this. John F. Kennedy's legs buckled beneath him as he slumped into his chair.

For nearly a minute he sat there, silent, staring at a black-framed photograph of his wife,

Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy. She had died in his arms two months ago, murdered by an

assassin's bullet meant for him. More than ever, the President wished that she were here now.

Despite all the infidelities and the lies and the coldness that had been between them, he still loved

her like he had loved no other woman.

'Mr President? Mr President, what's our reply?' asked McNamara.

Jackie, thought Kennedy, why did you have to die? It still seemed unreal, like watching a car

accident – something happening to somebody else. Not to her.

He remembered he had been angry with her. It was a sultry day in Dallas, with the blazing sun

turning early morning rain into stifling humidity. Several times in the motorcade's slow trip

through the city the President had snarled at the First Lady to remove her sunglasses, so that the

throngs lining the sidewalks could see her smiling eyes: a husband berating his wife over

something so trivial, all the while smiling falsely for the strangers surrounding them.

Then the shots started. The first sounded just like a firecracker going off; it had hardly seemed

real at all. Then something slapped Kennedy in the back of the neck and he found it hard to

breathe, to call out a warning. Then that fatal third shot and a blur of motion: Jackie's head

exploding; the blood and bone and brain showering the President in a pink spray; his wife

slumping slowly over into his lap.

They had rushed her to Parkland Memorial Hospital, but she was pronounced dead on arrival.

The security alerts followed; a hurried trip back to Washington in case there were any further

attempts on his life; not even time to wait for his wife's body to be loaded on to Air Force One, the

presidential jet.

Since the funeral John Fitzgerald Kennedy had been like a ghost himself, he now realized. He

had let this conflict escalate as he mourned; ignored the warning signs; been too wrapped up in

his own grief. But most of all, he had been wracked with guilt: about his philandering; about his

lies to her; about how he had insisted she go on that trip to Texas to bolster his popularity in a

Southern state that would be crucial in the following year's presidential elections. The Texas trip

was the first time Jackie had accompanied him on a political visit anywhere within America since

his election back in 1960. It was also her last.

'Jack? Jack! You've got to make a decision – now!'

The President snapped out of his reverie. He looked for McNamara before speaking, his voice

firm and gruff. 'Get the Bagman in here.'

The Secretary of Defense stepped to the door, opened it, and nodded. In stepped Ira Gearhart,

a dark-suited Secret Service agent, carrying a small suitcase with a device not unlike a safe dial

attached to its locking mechanism. He strode to the desk and placed the suitcase by the

President. Kennedy nodded and Gearhart quickly flicked the dial through its complex combination

sequence.

The suitcase sprung open and the President looked down at the electronic mechanism inside.

With this piece of equipment he could call for a retaliatory nuclear strike, and make sure that

America did not burn alone. Or he could pause; refuse to retaliate; let his nation die to show the

world why this should never happen again. If he did that, at least there might still be a world left

after today. This was a decision that Kennedy prayed each night he would never have to face.

Now the decision was his, and his alone. 'How long?' he asked.

'Less than two minutes,' snapped McNamara. 'You must act now, or else our war birds will be

dead in the silos. We'll be wiped out!'

The President looked to his brother. In a family of staunch Roman Catholic upbringing, Bobby

Kennedy had always been the one of deepest beliefs and greatest faith. Jack frequently used his

brother as a moral compass to guide his proper course of action in matters of the conscience. But

now his brother's face was impassive. The decision had to be made, and it had to be made by the

President himself. It was time.

John F. Kennedy closed his eyes and tapped the secret code into the machine. The code was

sent to the missile silos around the nation, where soldiers stood ready to launch the deadly

payload they guarded. Within sixty seconds, thousands of nuclear weapons would fly forth from

the ground, carrying death through the sky.

The President sat back in his chair and felt curiously calm. Now that the irrevocable decision

had been taken, a weight had lifted from his shoulders. Perhaps this was how the suicidal felt as

they fell through the air towards their deaths.

Kennedy looked at the faces of those around him. Many had tears rolling down their faces;

others were firm and resolute; several were praying. The President realized they were expecting

him to speak; to comfort and reassure them; to say that this was the only course; they had had

no choice; that everything would be all right really.

Instead all his mind was wracked by one of those niggling, trivial questions that you know the

answer to, but you just cannot remember it. What was it the director of the Manhattan Project,

Doctor Robert Oppenheimer, had said when he witnessed the first explosion of an atom bomb?

Something from a Hindu epic poem . . .

Kennedy almost smiled as he remembered the answer: 'I am become Death, the Destroyer of

Worlds'. But that was not what the people in the Oval Office wanted to hear right now. Instead

John Fitzgerald Kennedy bowed his head and whispered quietly as the world came to an end: 'May

God have mercy on all our souls.'

22 January 1996

The incident just described never happened.

It was President John F. Kennedy who was assassinated on 22 November 1963, not his wife.

The man who was arrested for Kennedy's murder, Lee Harvey Oswald, was found to have links to

the Soviet Union, but was himself murdered a few days later. There was no trial, and when new

President Lyndon Johnson set up a tribunal to investigate the matter, the Warren Commission

decided that Oswald had acted alone. America and the world lost much of its innocence that tragic

day in Dallas. The world survived when Kennedy did not. But perhaps the world survived because

Kennedy did not.

What if JFK had lived? What if the assassination had never taken place, or the bullets had only

wounded the president? What effect would that have had on the world? I wrote a book published

in 1971 that speculated about just such a situation. My book suggested that Kennedy would have

been re-elected for a second term and carved out a new era of prosperity for the Western World.

It is a measure of the world's cynicism today that a novel recently published speculated

Kennedy would have simply become old, fat and discredited, and not the mythic figure he is now.

Kennedy symbolized so much about this century and about America, that it is hard to imagine

how history would view his achievements had he lived longer.

Consider this: if he had lived, John Fitzgerald Kennedy would be 79 years old when this book is

published, going on 80. It's difficult to imagine JFK as a 79-year-old. While his contemporaries

have withered and died, he remains forever young, preserved in our collective memory as the

smiling-faced man whose head was blown open by an assassin's bullet.

The killing of President Kennedy has had a profound effect on the entire world, and has

changed the course of history. Every adult who was alive that day can remember what they were

doing when they heard of Kennedy's death; it sent a shockwave around the world that

reverberates to this day. But his death has had a particular effect on my life.

It was my eighteenth birthday the day JFK was murdered. I had always wanted to become a

cadet reporter, and as a special pre-arranged birthday treat I was taken to spend the day on work

experience at the offices of the 8 O'Clock, a Saturday-evening newspaper in Auckland, New

Zealand. Kennedy was assassinated just after midday on Friday 22 November in Dallas, Texas.

(Because of the International Dateline, it was early on the morning of Saturday 23 November in

New Zealand when JFK died.)

I never had an eighteenth birthday party; never marked my coming of age as many adults do.

Instead I spent the day acting as copy-runner, coffee maker and library assistant at the 8 O'Clock

offices, helping to put together a special memorial edition of the paper.

Traditionally, the 8 O'Clock was a place to read reports and results from sports fixtures. It had

a news section, but this was merely an adjunct of its parent paper, the Auckland Star. But for

once, thanks to quirks of timing and international time differences, a story had fallen into the 8

O'Clock's lap – the biggest story of the decade. After that day, it was inevitable that I would be a

journalist – what other job could be that exciting?

The world lost its innocence that day and I left behind my childhood at the same time. More

than three decades have passed since then, and every year we learn a little bit more about JFK:

his womanizing, his vanity, his human frailties. But still the myth of Camelot – a glorious time

when the world was a better place – grows ever stronger.

After the death of John F. Kennedy, I became fascinated with the late, lamented president and

began what has proved to be a lifetime of research into what really happened that day in Dallas.

Meanwhile, the investigative skills I was developing in my spare time were paying off at work. I

pursued a career in journalism: first as a cadet in the provinces, then a shift to the big

metropolitan papers. There I learnt about writing and researching, making contacts and fostering

friendships, sub-editing and betrayal and ambition. I also learnt about my past.

I was born on 23 November 1945, the illegitimate son of an American GI stationed in New

Zealand on his way to the war in the Pacific. When my mother told him she was pregnant, he

became furious with her, refused to acknowledge his responsibilities, and accused her of being a

whore. My mother was only seventeen. The GI went off to war, leaving her with nothing. He died

two weeks later, the victim of friendly fire.

To be an unmarried pregnant girl of seventeen in New Zealand during the Second World War

made you as much of a social outcast as if you were a leper. The fact that my mother came from

one of Auckland's wealthiest and most influential families just made her shame greater. Twice she

tried to kill herself, without success. When I was born, I was immediately put up for adoption.

My foster parents told me on my 21st birthday that I had been adopted, but it came as little

surprise. There had always been a barrier between myself and the rest of the family; now I knew

the real reason why. I determined to find out all I could about my past so I could confront my

natural mother – why she had abandoned me.

Eventually, when I had learnt all I could, I went to my natural mother's family home in

Remuera, Auckland's richest residential area. The house was an immense wooden mansion, with a

carefully raked gravel driveway and a gardener trimming the high hedges that shielded the

property from view of the road.

I pushed the front-door bell and a cold-faced woman in her mid-forties answered it. Her

greying hair was pulled back from her face, and her eyes were dead inside. I turned and walked

away, ignoring her questions. There was no love in her, yet she was richer than I could ever hope

to become in New Zealand. It was time to move on.

Nearly five years after that fateful day in Dallas, I left for Britain with the ambition to work in

Fleet Street – the home of newspaper journalism. I arrived in England in 1968. Across the

Atlantic, Robert Kennedy was assassinated – shot down like his brother before him. The golden

age of Camelot was long gone, and the world was becoming ever more bitter and cynical: the

escalating war in Vietnam; growing conflict between generations; and the gap between rich and

poor always expanding. What had been a decade of idealism and the urge to change things for the

better seemed to have turned sour.

I never really abandoned my fascination for the Kennedy family and its tragedies, but instead

concentrated on my career, on myself. Looking back now, I realize that I became as selfish and

cynical and bitter as the rapidly approaching new decade. Of course I flourished, moving quickly

from worthy provincial papers to the gutter press of Fleet Street, my rise taking months when

most take years.

My training in New Zealand stood me in good stead, and I soon landed a top job on the Daily

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

WHOKILLEDKENNEDYWHOKILLEDKENNEDYTheshockingsecretlinkingaTimeLordandaPresidentDavidBishop&JamesStevensFirstpublishedinGreatBritainin1996byDoctorWhoBooksanimprintofVirginPublishingLtd332LadbrokeGroveLondonW105AHCopyright©DavidBishop1996TherightofDavidBishoptobeidentifiedastheAuthorofthisWorkhasbeenas...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:156 页

大小:1.63MB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-05

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394