Kim Stanley Robinson - Antarctica

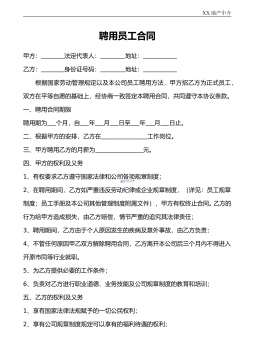

VIP免费

2024-12-04

1

0

1.03MB

238 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

ANTARCTICA

Kim Stanley Robinson

"The land looks like a fairytale.

- ROALD AMUNDSEN

1. Ice Planet

2. Science in the Capital

3. In the Antarctic Grain

4. Observation Hill

5. A Site of Special Scientific Interest

6. In the Footsteps of Amundsen

7. Down the Rabbit Hole

8. The Sirius Group

9. Big Trouble

10. Roberts Massif

11. Extreme Weather Event

12. Transantarctica

13. The McMurdo Convergence

14. From the Bottom Up

15. Shackleton's Leap

1. Ice Planet

First you fall in love with Antarctica, and then it breaks your heart.

Breaks it first in all the usual sorry ways of the world, sure-as for instance when you go down to the ice

to do something unusual and exciting and romantic, only to find that your job there is in fact more tedious

than anything you have ever done, janitorial in its best moments but usually much less interesting than

that. Or when you discover that McMurdo, the place to which you are confined by the strictest of

company regulations, resembles an island of traveler services clustered around the offramp of a freeway

long since abandoned. Or, worse yet, when you meet a woman, and start something with her, and go with

her on vacation to New Zealand, and travel around South Island with her, the first woman you ever really

loved; and then after a brief off-season you return to McMurdo and your reunion with her only to have her

dump you on arrival as if your Kiwi idyll had never happened. Or when you see her around town soon

after that, trolling with the best of them; or when you find out that some people are calling you "the

sandwich, " in reference to the ice women's old joke that bringing a boyfriend to Antarctica is like

bringing a sandwich to a smorgasbord. Now that's heartbreak for you.

But then the place has its own specifically Antarctic heartbreaks as well, more impersonal than the

worldly kinds, cleaner, purer, colder. As for instance when you are up on the polar plateau in late winter,

having taken an offer to get out of town without a second thought, no matter the warnings about the

boredom of the job, for how bad could it be compared to General Field Assistant? And so there you are

riding in the enclosed cab of a giant transport vehicle, still thinking about that girlfriend, ten thousand feet

above sea level, in the dark of the long night; and as you sit there looking out the cab windows, the sky

gradually lightens to the day's one hour of twilight, shifting in invisible stages from a star-cluttered black

pool to a dome of glowing indigo lying close overhead; and in that pure transparent indigo floats the

thinnest new moon imaginable, a mere sliver of a crescent, which nevertheless illuminates very clearly the

great ocean of ice rolling to the horizon in all directions, the moonlight glittering on the snow, gleaming

on the ice, and all of it tinted the same vivid indigo as the sky; everything still and motionless; the clarity

of the light unlike anything you've ever seen, like nothing on Earth, and you all alone in it, the only

witness, the sole inhabitant of the planet it seems; and the uncanny beauty of the scene rises in you and

clamps your chest tight, and your heart breaks then simply because it is squeezed so hard, because the

world is so spacious and pure and beautiful, and because moments like this one are so transient-impossible

to imagine beforehand, impossible to remember afterward, and never to be returned to, never ever. That's

heartbreak as well, yes- happening at the very same moment you realize you've fallen in love with the

place, despite all.

Or so it all happened to the young man looking out the windows of the lead vehicle of that spring's

South Pole Overland Traverse train-the Sandwich, as he had been called for the last few weeks, also the

Earl of Sandwich, the Earl, the Duke of Earl (with appropriate vocal riff), and the Duke; and then, because

these variations seemed to be running thin, and appeared also to touch something of a sore spot, he was

once again referred to by the nicknames he had received in Antarctica the year before: Extra Large, which

was the size announced prominently on the front of his tan Carhartt overalls; and then of course Extra; and

then just plain X. "Hey X, they need you to shovel snow off the comms roof, get over there!"

After the sandwich variations he had been very happy to return to this earlier name, a name that anyway

seemed to express his mood and situation-the alienated, anonymous, might-as-well-be-illiterate-and-

signing-his-name-with-a-mark General Field Assistant, the Good For Anything, The Man With No Name.

It was the name he used himself-"Hey Ron, this is X, I'm on the comms roof, the snow is gone. What next,

over. "-thus naming himself in classic Erik Erikson style, to indicate his rebirth and seizure of his own life

destiny. And so X returned to general usage, and became again his one and only name. Call me X. He was

X.

The SPOT train rolled majestically over the polar cap, ten vehicles in a row, moving at about twenty

kilometers an hour-not bad, considering the terrain. X's lead vehicle crunched smoothly along, running

over the tracks of previous SPOT trains, tracks that were in places higher than the surrounding snow, as

the wind etched the softer drifts away. The other tractors were partly visible out the little back window of

the high cab, looking like the earthmovers that in fact had been their design ancestors. Other than that,

nothing but the polar plateau itself. A circular plain of whiteness, the same in all directions, the various

broad undulations obscure in the starlight, obvious in the track of reflected moonlight.

As the people who had warned him had said, there was nothing for him to do. The train of vehicles was

on automatic pilot, navigating by GPS, and nothing was likely to malfunction. If something did, X was not

to do anything about it; the other tractors would maneuver around any total breakdowns, and a crew of

mechanics would be flown out later to take care of it. No-X was there, he had decided, because somebody

up in the world had had the vague feeling that if there was a train of tractors rolling from McMurdo to the

South Pole, then there ought to be a human being along. Nothing more rational than that. In effect he was

a good-luck charm; he was the rabbit's foot hanging from the rear-view mirror. Which was silly. But in his

two seasons on the ice X had performed a great number of silly tasks, and he had begun to understand that

there was very little that was rational about anyone's presence in Antarctica. The rational reasons were all

just rationales for an underlying irrationality, which was the desire to be down here. And why that desire?

This was the question, this was the mystery. X now supposed that it was. A different mix of motives for

every person down there- explore, expand, escape, evaporate-and then under those, perhaps something

else, something basic and very much the same for all-like Mallory's explanation for trying to climb

Everest: because it's there. Because it's there! That's reason enough!

And so here he was. Alone on the Antarctic polar plateau, driving across a frozen cake of ice two miles

thick and a continent wide, a cake that held ninety-five percent of the world's fresh water, etc. Of course it

had sounded exciting when it was first mentioned to him, no matter the warnings. Now that he was here,

he saw what people had meant when they said it was boring, but it was interesting too-boring in an

interesting way, so to speak. Like operating a freight elevator that no one ever used, or being stuck in a

movie theater showing a dim print of Scott of the Antarctic on a continuous loop. There was not even any

weather; X traveled under the alien southern constellations with never a cloud to be seen. The twilight

hour, which grew several minutes longer every day, only occasionally revealed winds, winds unfelt and

unheard inside the cab, perceptible to X only as moving waves of snow seen flowing over the white

ground.

Once or twice he considered gearing up and going outside to cross-country ski beside the tractor; this

was officially forbidden, but he had been told it was one of the main forms of entertainment for SPOT

train conductors. X was a terrible athlete, however; his last adolescent sprout had taken him to six foot ten

inches tall, and in that growth he had lost all coordination. He had tried to learn cross-country skiing on

the prescribed routes around McMurdo, and had made a little progress; and sometimes it was a tempting

idea to break the monotony; but then he considered that if he fell and twisted an ankle, or stunned himself,

the SPOT tractors would continue to grind mindlessly on, leaving him behind trying to catch up, and no

doubt failing.

He decided to pass on going outside. Monotony was not such a bad thing. Besides there would be some

crevasse fields to be negotiated, even up here on the plateau, where the ice was often smooth and solid for

miles at a time. Although it was true that the Army Corps of Engineers had mitigated all crevasses they

didn't care to outflank, meaning they had blown them to smithereens, then bulldozed giant causeways

across the resulting ice-cube fields. This process had created some dramatic passages on the Skelton

Glacier, which rose from the Ross Sea to the polar plateau in less than thirty kilometers, and was therefore

pretty severely crevassed in places, so much so that the Skelton had not been the preferred route for

SPOT; the first trains had crossed the Ross Ice Shelf and ascended the Leverett Glacier, a gentler incline

much farther to the south. But soon after SPOT had become operational, and quickly indispensable for the

construction of the new Pole station, the Ross Ice Shelf had begun to break apart and float away, except

for where it was anchored between Ross Island and the mainland. The Skelton route could make use of

this remnant portion of the shelf, and so every year the Corps of Engineers re-established it, and off they

went. X's nighttime ascent of the Skelton, through the spectacular peaks of the Royal Society Range, had

been the most exciting part of his trip by far, crunching up causeway after causeway of crushed ice

concrete, with serac fields like dim shattered Manhattans passing to right and left.

But that had been many days ago, and since reaching the polar plateau there had not been much

excitement of any sort. The fuel depots they passed were automated and robotic; the vehicles stopped one

by one next to squat green bladders, were filled up and then moved on. If any new crevasses had opened

up across the road since the last passing of a train, the lead vehicle's pulse radar would detect it, and the

navigation system would take appropriate action, either veering around the problem area or stopping and

waiting for instructions. Nothing of that sort actually happened.

But he had been warned it would be this way, and was ready for it. Besides, it was not that much

different from all the rest of the mindless work that Ron liked to inflict on his GFAs; and here X was free

of Ron. And he wasn't going to run into anyone he didn't want to, either. So he was content. He slept a lot.

He made big breakfasts, and lunches, and dinners. He watched movies. He read books; he was a voracious

reader, and now he could sit before the screen and read book after book, or portions of them, tracking

cross-references through the ether like any other obsessive young gypsy scholar. He made sure to stop

reading and look out the windows at the great ice plain during the twilights bracketing noon, twilights that

grew longer and brighter every day. Though he did not experience again anything quite as overwhelming

as the indigo twilight of the crescent moon, he did see many beautiful predawn skies. The quality of light

during these hours was impossible to get used to, vibrant and velvet beyond description, rich and

transparent, a perpetual reminder that he was on the polar cap of a big planet.

Then one night he got some weather. The stars were obscured to the south, the rising moon did not rise

on schedule, though clearly it had to be up there, no doubt shining on the top of the clouds and, yes,

making them glow just a little, so that now he could see them rushing north and over him, like a blanket

pulled over the world; no stars, now, but a dim cloudy rushing overhead; and then through the thick

insulation of the cab he could for once hear the wind, whistling over and under and around his tractor. He

could even feel the tractor rock just a tiny bit on its massive shock absorbers. A storm! Perhaps even a

superstorm!

Then the moon appeared briefly through a gap, nearly a half moon now, full of mystery and

foreboding, flying fast over the clouds, then gone again. Black shapes flicked through the clouds like bats.

X blinked and rubbed his eyes, sure that he was seeing things.

A light tap tapped on the roof of his vehicle. "What the hell?" X croaked. He had almost forgotten how

to talk.

Then his windshield was being covered by a sheet of what looked like black plastic. Side windows and

back window also. X could see gloved fingers working at the edges of the plastic, reaching down from

above to tape the sheets in place. Then he could see nothing but the inside of the cab.

"What the hell!" he shouted, and ran to the door, which resembled a meat-locker door in both

appearance and function. He turned the big handle and pushed out. It didn't move. It wouldn't move. There

were no locks on these tractor doors, but now this one wouldn't open.

"What-the-hell, " X said again, his heart pounding. "HEY!" he shouted at the roof of the vehicle. "Let

me out!" But with the vehicle's insulation there was no way he would be heard. Besides, even if he were...

He ran down the narrow low stairs leading from the cab into the vehicle's freight room. On one side of

the big compartment were two big loading doors that opened outward, but when he twisted the latch locks

down, and turned the handles and pushed out, these doors too remained stubbornly in place. They were

not as insulated as the cab doors, and when he pushed out on them hard, a long crack of windy darkness

appeared between them. He put an eye to the thin gap, and felt the chill immediately: fifty degrees below

zero out there, and a hard wind. There was a plastic bar crossing the gap just below eye level; no doubt it

was melted or bonded to the doors, and holding them shut. "Hey!" he bellowed out the crack. "Let me out!

What are you doing!"

No answer. His face was freezing. He pulled back and blinked, staring at the crack. The bar was

welded or glued or otherwise bonded across the doors, locking them in place. No doubt it was the same

up there on the outside of the cab door.

He recalled the emergency hatch in the roof of the cab, there in case the vehicle fell through sea ice or

got corked in a crevasse, so that the occupants had to make their escape upward. X had thought it a pretty

silly precaution, but now he ran back and pulled that handle around to the open position, a very stiff

handle indeed, and shoved up. It wouldn't go. Stuck. He was trapped inside, and the windshield and cab

windows were covered. All in about two minutes. Ludicrous but true.

He thought over the situation while putting on the layers of his outdoor clothing: thick smartfabric

pants and coat, insulated Carhartt overalls, heavy parka, gloves and mittens. He would need it all outside,

if he could get outside, but now he began to overheat terribly. Sweating, he turned on the radio and

clicked it to the McMurdo comms band. "Hello McMurdo, McMurdo, this is SPOT number 103, SPOT

calling Mac Town do you read me over over. " While he waited for a reply he went to one of the closets

of the cab, and pulled a brand new hacksaw from a tool chest.

"SPOT 103, through the miracle of radio technology you have once again manipulated invisible

vibrations in the ether to reach Mac Comms, hey X, how are you out there, over. "

"Not good Randi, I think I'm being hijacked!"

"Say again X, I did not copy your last message, over. "

"I said I am being hijacked. Over!"

"Hey X, lot of static here, sounded like you said say Hi to Jack, but Jack's out in the field, tell me what

you mean, if that's what you said, over. "

"Hi-JACKED. Someone's locked me in the cab here and taped over the windows! Over!"

"X, did you say hijacked? Tell me what you mean by hijacked, over. "

"What I mean is that I'm in a storm up here and just now some, somebody landed on my roof and

covered my windows on the outside with black plastic, and none of my doors will open, something has

been done to them on the outside to keep them from opening! So I'm going to go back and try to cut

through a bar holding the back doors together, but I thought I'd better call you first, in case, to tell you

what's happening! Also to ask if you can see anything unusual about my train in any satellite images you

have of it! Over!"

"We'll have to check about the satellite images, X, I don't know who is getting those, if anyone. Just

stay put and we'll see what we can do. Don't do anything rash, over. "

"Yeah yeah yeah, " X muttered, and pushed the transmit button: "Listen Randi, I'm going to go to the

back doors and see if they'll open, be right back to tell you about it, over!"

He went to the back and shoved out on the doors again. Again they stopped, but this time he fit the

hacksaw into the crack over the bar, and began to saw like a maniac. Some kind of hardened plastic,

apparently, and the doors impeded the saw. By the time he cut through the bar he was sweating profusely,

and when he flung the doors open the air crashed over him like a wave of liquid nitrogen. "Ow!" he said,

his throat chilling with every inhalation. He pulled his parka hood up, and held onto the door and leaned

out into the wind, his eyes tearing so he could barely see.

But he had a door open. He was no longer trapped. He leaned out to look; the next vehicle in the line

was following as if nothing had happened. It was like being in a train of mechanical elephants. No one in

sight, nothing to be seen. Rumbling engines, squeaks of giant tractor wheels over the dry snow, the

whistle and shriek of the wind; nothing else; but a gust of fear blew through him on the wind, and he

shivered convulsively. He needed more clothes. Back up in the cab he could hear Randi's voice, a clear

Midwestern twang that cut through static like nothing else: "Mac Comms calling SPOT 103, answer me

X, what's happening out there? Weather says you're in a Condition One out there, so be careful! They also

said their satellite photos do not penetrate the cloud layer in any way useful to you. Answer me X, please,

over!"

Instead he dropped down the steps and onto the hard-packed snow beside the vehicle. It squeaked

underfoot. "Shit. " He ran forward and leaped onto the ladder steps that were inset into the lower body of

the cab. Black plastic on the windows, sure enough. "Shit!" He tore at it, and the freezing wind helped

pull the sheet away from the metal and plastic; he held onto the sheet with a desperate clench, so he would

have evidence that he had not hallucinated the whole incident. Then he hesitated, irrationally afraid of

jumping down wrong somehow and screwing up, as in his ski fantasy. But surely in the state he was in, he

could run a lot faster than the tractors were moving; and it was too cold to stay where he was, the wind

was barreling right through his clothes and his flesh too, rattling his bones together like castanets. So he

leaped down, and landed solidly, and as his tractor lumbered past he ran out of the line of the treadmarks,

to be able to see back the length of the train. It looked short. He counted to be sure, pointing at each

tractor in turn; while he did his vehicle got a bit ahead of him, and when he noticed that he ran like a

lunatic back to the side of the thing, and leaped up and in, panting hard, frightened, frozen right to the

core. There were only nine vehicles now.

High rapid beeping came from her crevasse detector, and Valerie Kenning stopped skiing and leaned

on her ski poles. She was well ahead of the rest of her group, and with a check over her shoulder to make

sure they were coming on okay, she stabbed her poles deeper into the dry snow of the Windless Bight,

causing a last little surge of heat in the pole handles, and took the pulse radar console out of its parka

pocket and looked at the screen, thumbing the buttons to get a complete read on the terrain. A

beepbeepbeep; there was a fairly big crevasse ahead. They were entering the pressure zone where the

Ross Ice Shelf used to push around the point of Cape Crozier, and though the pressure was gone the

buckling was still there, causing many crevasses.

She approached this one slowly and got a visual sighting: a slight slump lining the snow. She would

have noticed it, but there were many others that were invisible. Thus her love for the crevasse detector,

like a baseball catcher's love for his mask. Now she used it to check the crevasse for a usable snowbridge.

The music of the beeps played up and down-higher and faster over thin snow, lower and slower over the

thicker bits. In one broad region to her left, snow filled the crevasse with a thickness and density that

would have held a Hagglunds. So Val unclipped from her sledge harness, plucked her poles out of the

snow and skied slowly across, shoving one ski pole down ahead of her in the old-fashioned test, more for

luck than anything else; by now she trusted the radar as much as any other machine she used.

She recrossed the bridge, snapped back into her sledge, pulled it across the crevasse, and stood waiting

for the others, chilling down as she did. While she waited she checked her GPS to scout their route

through the crevasses ahead. A bit of a maze. The three members of the 1911 journey to Cape Crozier, the

so-called "Worst Journey in the World, " had taken a week of desperate hauling to pass through this

region; but with GPS and the latest ice maps, Val's group of twenty-five would thread a course in only a

day, or two if Arnold slowed them too much.

There were only two days to go before the springtime return of the sun to Cape Crozier, and at this hour

of the morning Mount Erebus's upper slopes were bathed in a vibrant pink alpenglow, which reflected

down onto the blue snow of the shadowed slopes beneath it, creating all kinds of lavender and mauve

tints. Meanwhile the twilit sky was pinwheeling slowly through its bright but sunless array of pastels:

broad swathes of blues, purples, pinks, even moments of green; as Val slowly cooled down she had a good

look around, enjoying the moment of peace that would soon be shattered by the arrival of the pack. A

guide's chances to enjoy the landscapes she traveled through came a lot less frequently than Val would

have liked.

Then the pack was on her and she was back at work, making sure they all got across the snow bridge-

without accident, chatting with the perpetual cheerfulness that was her professional demeanor, pointing

out the alpenglow on Erebus, which was turning the steam cloud at its summit into a mass of pink cotton

candy thirteen thousand feet above them. This diverted them while they waited for Arnold. It was too cold

to wait comfortably for long, however, and many of them obviously had been sweating, despite Val's

repeated warnings against doing so. But even with the latest smartfabrics in their outfits, these folks were

not skillful enough at thermostatting to avoid it. They had overheated as they skied, and their sweat had

wicked outward through several layers whose polymer microstructures were more or less permeable

depending on how hot they got, the moisture passing through highly heated fabric freely until it was

shoved right out the surface of their parkas, where it immediately froze. Her twenty-four waiting clients

looked like a grove of flocked Christmas trees, shedding snow with every move.

Eventually a pure white Arnold reached them and crossed the snowbridge, and without giving him

much of a chance for rest they were off again through the crevasse maze. Although they were crossing the

Windless Bight, a strong breeze struck them in the face. Val waited for Arnold, who was puffing like a

horse, his steamy breath freezing and falling in front of him as white dust. He shook his head at her;

though she could see nothing of his face under his goggles and ski mask (which he ought to have pulled

up, sweating as he was), she could tell he was grinning. "Those guys," he said, with the intonation the

group used to mean Wilson, Bowers, and Cherry-Garrard, the three members of the original Crozier

journey. "They were crazy. "

"And what does that make us?"

Arnold laughed wildly. "That makes us stupid. "

black sky

white sea

Ice everywhere, under a starry sky. Dark white ground, flowing underfoot. A white mountain

puncturing the black sky, mantled by ice, dim in the light. An ice planet, too far from its sun to support

life; its sun one of the brighter stars overhead, perhaps. Snow ticking by like sand, too cold to adhere to

anything. Titan, perhaps, or Triton, or Pluto. No chance of life.

But there, at the foot of black cliffs falling into white ice, a faint electric crackle. Look closer: there-the

source of the sound. A clump of black things, bunched in a mass. Moving awkwardly. Black pears in

white tie. The ones on the windward side of the mass slip around to the back; they've taken their turn in

the wind, and can now cycle through the mass and warm back up. They huddle for warmth, sharing in turn

the burden of taking the brunt of the icy wind. Aliens.

Actually Emperor penguins, of course. Some of them waddled away from the newcomers on the scene,

looking exactly like the animated penguins in Mary Pop-pins. They slipped through black cracks in the

ice, diving into the comparative warmth of the -2° C. water, metamorphosing from fish-birds to bird-fish,

as in an Escher drawing.

The penguins were the reason Val's group was there. Not that her clients were interested in the

penguins, but Edward Wilson had been. In 1911 he had wondered if their embryos would reveal a missing

link in evolution, believing as he did that penguins were primitive birds in evolutionary terms. This idea

was wrong, but there was no way to find that out except to examine some Emperor penguin eggs, which

were laid in the middle of the Antarctic winter. Robert Scott's second expedition to Antarctica was

wintering at Cape Evans on the other side of Ross Island, waiting for the spring, when they would begin

their attempt to reach the South Pole. Wilson had convinced his friend Scott to allow him to take Birdie

Bowers and Apsley Cherry-Garrard on a trip around the south side of the island, to collect some Emperor

penguin eggs for the sake of science.

Val thought it strange that Scott had allowed the three men to go, given that they might very well have

perished, and thus jeopardized Scott's chances of reaching the Pole. But that was Scott for you. He had

made a lot of strange decisions. And so Wilson and Bowers and Cherry-Garrard had manhauled two

heavy sledges around the island, in their usual style: without skis or snowshoes, wearing wool and canvas

clothing, sleeping in reindeer-skin sleeping bags, in canvas tents; hauling their way through the thick drifts

of the Windless Bight in continuous darkness, in temperatures between -40 and -75 degrees Fahrenheit:

the coldest temperatures that had ever been experienced by humans for that length of time. And thirty-six

days later they had staggered back into the Cape Evans hut, with three intact Emperor penguin eggs in

hand; and the misery and wonder they had experienced en route, recounted so beautifully in Cherry-

Garrard's book, had made them part of history forever, as the men who had made the Worst Journey in the

World.

Now Val's group was in a photo frenzy around the penguins, and the professional film crew they had

along unpacked their equipment and took a lot of film. The penguins eyed them warily, and increased the

volume of their collective squawking. The newest generation of Emperors were still little furballs, in great

danger of being snatched by skuas wheeling overhead, the skuas trying some test dives and then skating

back on the hard wind to the Adelie penguin rookery at the north end of the cape. As always, Cape Crozier

was windy.

Val's clients finished their photography, and then were not inclined to stay and observe the Emperors

any longer; the wind was too biting. Even dressed in what Arnold called spacesuits, a wind like this one

cut into you. So they quickly regathered around Val. George told her they were hoping that they would

still have time in the brief twilight to climb Igloo Spur and look for the circle of rocks that Wilson,

Bowers, and Cherry-Garrard had left behind.

"Sure, " Val said, and led them to the usual campsite at the foot of Igloo Spur, and told them to go on

up and have a look while there was still some twilight left. She would set a security tent and then follow.

George Tremont, the leader of the expedition, which was not just another Footsteps re-enactment but a

special affair, went into conference with Arnold, his producer, and the cinematographer and camera crew.

They had to decide if they should film this moment as the true live hunt for the rock circle, or else find it

today and then film a hunt tomorrow, in a little re-enactment of their own.

Val had very little patience for this kind of thing. Her GPS had the coordinates for the "Wilson Rock

Hut, " as the Kiwi maps called it, and so they could have hiked up the spur and found the thing

immediately. But no; this was not to be done. George and the rest wanted to film a finding of the rock

igloo without mechanical aid. They seemed to assume that their telecast's audience would be so ignorant

that they would not immediately wonder why GPS was not being used. Val doubted this notion, but kept

her thoughts to herself, and concentrated on setting up one of the big team tents, looking up once or twice

at the gang tramping up the ridge, with their cameras but without GPS. It was pure theater.

After she had the tent up, and the sledges securely anchored, she hiked up the spine of the lava ridge.

About five hundred feet over the sea ice the ridge leveled off, and fell and rose a few times before joining

the massive flank of Mount Terror, Erebus's little brother. As she had expected, she found her group still

hunting for the rock hut, scattered everywhere over the ridge. In the dim tail end of the twilight this kind

of wandering around could be dangerous; Cape Crozier was big and complicated, its multiple lava ridges

separating lots of tilted and crevassed ice slopes running down onto the sea ice. When Mear and Swan had

re-enacted the Worst Journey for the first time, in 1986, they had lost their own tent in the darkness for a

matter of some hours, and if they hadn't stumbled across it again they would have died.

But now the wandering had to be allowed; this was the good stuff, the treasure hunt. The camera

operators were hopping around trying to stay out of each other's views, getting every moment of it on their

supersensitive film; it would be more visible on screen than it was to the naked eye. And everyone had a

personal GPS beeper in their parka anyway, so if someone did disappear, Val could pull out the finder unit

and track them down. So it was safe enough.

The searchers, however, were beginning to look like a troop of mimes doing impressions of Cold

Discouragement. The truth was that the rock igloo that the three explorers had left behind was only knee

high at its highest point, and both it and the plaque put there by the Kiwis had been buried in the last

decade's heavy snowfalls; though most of the snow here had been swept to sea by the winds, enough had

adhered in the black rubble to make the whole ridge a dense stippling of black and white, hard to read in

the growing darkness. Every large white patch on the broad ridge looked more or less like a knee-high

rock circle, and so did the black patches too.

So hither and yon Val's clients wandered, calling out to each other at every pile of stone or snow.

Several were trying to read their copies of The Worst Journey in the World by flashlight, to see if the text

could direct them. Val heard some complaining about the vagueness of Cherry-Garrard's descriptions,

which was not very generous given that young Cherry had been terribly near-sighted and had not been

able to wear his thick glasses because they kept frosting up, so that among the other remarkable aspects of

the Worst Journey was the fact that one of the three travelers, and the one who ended up telling their tale,

had been functionally blind. A kind of Homer and Ishmael both.

Val sat on a waist-high rock next to a couple of the film crew, who had given up filming for the

moment and were plugging their gloves into a battery heater and then clasping chocolate bars in the hope

of thawing them a bit before eating. They were laughing at George, who was now consulting a copy of Sir

Edmund Hillary's book No Latitude for Error, which recounted the first discovery of the rock hut, forty-

six years after it had been built. Hillary and his companions had been out testing the modified farm

tractors they would later drive up Skelton Glacier to the South Pole, and once at Cape Crozier they had

wandered around like Val's companions were now, with their own copy of Cherry-Garrard's book and

nothing more; essentially theirs had been the experience Val's companions were now trying to reproduce,

for at that time Cherry-Garrard's description of the site was the only guide anyone could have, with no

GPS or anything else to help. So Hillary and his companions had argued over Cherry's book line by line,

just like Val's group was doing now, only in genuine rather than faked frustration, until Hillary himself

had located the hut.

His book's account of the discovery, however, also proved to have a certain vagueness to it, as if the

canny mountaineer had not wanted to reveal an exact route. Although he had said, as George was

proclaiming now, that the hut was right on the line of the ridge, and in a saddle. " 'As windy and

inhospitable a location as could be imagined!'" George read in an angry shout.

"We should be filming this, " Geena noted.

"Elka's getting it, " Elliot said calmly.

Sir Edmund was proving as little help as Cherry-Garrard. It occurred to Val that someone could also

look up the relevant passages in Mear and Swan's In the Footsteps of Scott, for those first re-enacters, the

unknowing instigators of an entire genre of adventure travel, had also relocated the hut in the pre-GPS era,

and had published a good photo of it in their book. But it was a coffee-table book, Val recalled, and

probably no one had wanted to carry the weight. Anyway no book was going to help them on this dark

wild ridge.

Elliot echoed her thought: "A classic case of the map not being the territory. "

"Although a map would help. I don't think they're gonna find it without GPS. "

"Has to be here somewhere. They'll trip over it eventually. "

"It's too dark now. "

And the wind was beginning to hurt. People were beginning to crab around with their backs to the wind

no matter which way they were going. It was loud, too, the wind moaning and keening dramatically

over the broken rock.

"I'll give you even odds they find it. "

"Taken. "

"I can't believe they camped in such an exposed place. "

"They wanted to be close to the penguins. "

"Yeah, but still. "

Indeed, Val thought. She would never have set a camp here on the ridge; it was one of the last places on

Cape Crozier she would have chosen. And Wilson had known it was exposed to the wind, his diary made

that clear. But he had decided to risk it anyway, because he too had been concerned about losing their

camp in the darkness, and he had wanted it to be where they could find it at the end of their trips out to

look for penguins. Fair enough, but there were other places that would have been relocatable in the dark.

Putting it up here had almost cost them their lives. Oddly, Cherry-Garrard had claimed in his book that the

hut had been located on the lee side of the ridge, thus protected from direct blasts; he had also explained

that later aerodynamic science of which Wilson could not have been aware had revealed that the

immediate lee of a ridge was a zone of vacuum pull upward, which is what had yanked their roof off when

the wind reached Force Ten. But since the shelter actually was right on the spine of the ridge, as Hillary

had noted (Val was pretty sure she could see it down in the saddle below her, a big hump of snow among

other big humps of snow) it was hard to know what Cherry had been getting at-either making excuses for

Wilson's bad judgment, or else so blind he truly hadn't known where they had been.

"It certainly looks like another stupid move to be chalked up against the Scott expedition, " Elliot said.

"Maybe it's infectious, " Geena said. "A regional thing. "

"Below the 40th latitude south, " Elliot intoned "there is no law. Below the 50th, no God. And below

the 60th, no common sense. "

"And below the 70th, " Geena added, "no intelligence whatsoever. "

There was little Val could say to contradict them. After all, here were a couple dozen people staggering

around in a frigid wind, just to the left, the right, the before and the beyond of an oval rock wall that any

of them could have found after a ten-second consultation with their GPS. One of them was actually

tripping over the end of the shelter at this very moment!

But Val said nothing.

It got colder.

"These Footstep things, " Geena complained. "Want some hot chocolate?"

"I like them, " Elliot said, taking the thermos from her. "You get to add historical footage to the usual

stuff, it's great. "

"Be careful, it's hot. "

"I worked for Footsteps Unlimited for a while. Popularly known as F. U., because that's what the

clients' were most likely to say to each other after they got back. "

"Ha ha. "

"I also freelanced for Classic Expeditions of the Past Revisited, which its guides called Stupid

Expeditions of the Past Revisited, because the trip designers always chose the very worst trips in history,

sometimes with the original gear and food. "

"You're kidding. "

"No. But you'll notice they're out of business now. "

"Masochist travel-a new genre, still underappreciated. "

"It'll catch on. All travel is masochist. People will do anything. I shot Hannibal's crossing of the Alps,

elephants included-Marco Polo, Italy to China by camel-Scott's walk to the Pole-Napoleon's retreat from

Moscow. " He pulled up his facemask and drank from the thermos. "That one was colder than this. "

"Wow. I shot a gig with Condemned to Repeat It once, where we followed Stanley's hunt for

Livingstone. People said it was more dangerous to do now than it was then. "

"Condemned to Repeat It?"

"You know-those who know history too well are condemned to repeat it. "

"Ah yeah. But some of those old trips are unrepeatable no matter what, because they were impossible

in the first place. "

"Sure. I heard Shackleton's boat journey was a total disaster. "

Val's stomach tightened. She had guided that one herself, and did not want to talk or think about it.

Now she saw Elliot making a gesture with his thumb up her way, to warn Geena. That's the guide right

there, shhhh, don't mention it! God. What a thing to be known for. Val had guided every Footsteps

expedition in Antarctica, from Mawson's death march to Borchgrevink's mad winter ship, even fictional

expeditions like the one in Poe's "Message Found in a Bottle" (including the whirlpool at the end), or in

Le Guin's "Sur" (the latter of which ended with an emotional meeting with the author, the women

thanking her for the idea and also making many detailed suggestions for logistical additions to the text, all

of which Le Guin promised to insert the next time she revised it)-all these very difficult trips guided,

practically every early expedition in Antarctica re-enacted-and what was she remembered for? The fiasco,

of course.

Suddenly there were wild shouts from down the ridge. George and Ann-Marie were standing next to

the snowy hump Val had picked out as the likely site.

"Show time, " Elliot declared, and hefted his camera pack. "I hope this baby stays warm enough to keep

its focus. "

George had Elliot and Geena and the other camera operators shoot him and Ann-Marie re-enacting the

rediscovery of the hut, their shouts thin compared to the happy triumph of the originals. Then they

tromped back down to the dining tent, and ate the happiest meal they had had so far, while Val set up the

rest of the sleeping tents. After that they slept through the long dark hours of the night, snug in their

ultrawarm sleeping bags, on their perfectly insulated mattress pads. By the first glow of twilight on the

next day they were all back on the ridge and working around the mound, some of them carefully clearing

ice and snow away from the stacked rocks with hot-air blowers and miniature jackhammer-like tools, the

others building a little wooden shelter just up the ridge; for they were there to undo the work of Edmund

Hillary, so to speak, and return all of the belongings of Wilson's group that Hillary and his companions

had found and taken away.

The rock shelter itself was a small oval of rough stacked stones, many of them about as heavy as a

single person could lift. The old boys had been strong. The wall at its highest was three or four rocks tall.

The interior would have been about eight feet by five.

The old boys had been small. They had put one of their two sledges over the long axis of the oval, then

stretched their green Willesden canvas sheet over the sledge, and laid the sheet as far over the ground as it

would go, and loaded rocks onto this big valance, and rocks and snow blocks onto the roof itself, until

they judged the shelter to be as strong as they could make it. Bombproof; or so they had thought. A small

hole in the lee wall had served as their door, and they had set up their single Scott tent just outside this

entry way, to give them more shelter while affording the tent some protection from the wind, Val

assumed; Wilson's reason for setting up the tent when they had the rock shelter had never been clear to

her. Anyway, the shelter had been pretty damned strong, she could see; the wind that destroyed it had not

managed to pull the canvas out of its setting, but had instead torn it to shreds right in its place. As she had

on her previous visits, Val kneeled and dug into the snow plastering the chinks in the wall, and found

fragments of the canvas still there in the wall, more white than green. "Wow. "

And looking at the frayed canvas shreds, Val again felt a little frisson of feeling for the three men. It

was like looking at the gear in the little museum in Zermatt that Whymper's party had used in the first

ascent of the Matterhorn: rope like clothesline, shoes, light leather things, with carpenter's nails hammered

into the soles.... Those old Brits had conquered the world using bad Boy Scout equipment. Like this

frayed white canvas fragment between her fingers. A real piece of the past.

Not that they didn't have a great number of other, larger real pieces of the past, there with them now to

return to the site. For Wilson and his comrades had left in a hurry. The storm that had struck them had

first blown their tent away, and then blown the canvas roof off their shelter; after that they had lain in

their sleeping bags in a thickening drift of snow for two days, the temperatures in the minus 50s, the

wind-chill factor beyond imagining-singing hymns in the dark to pass the time, although with their tent

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

ANTARCTICAKimStanleyRobinson"Thelandlookslikeafairytale.-ROALDAMUNDSEN1.IcePlanet2.ScienceintheCapital3.IntheAntarcticGrain4.ObservationHill5.ASiteofSpecialScientificInterest6.IntheFootstepsofAmundsen7.DowntheRabbitHole8.TheSiriusGroup9.BigTrouble10.RobertsMassif11.ExtremeWeatherEvent12.Transantarct...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:238 页

大小:1.03MB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-04

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394