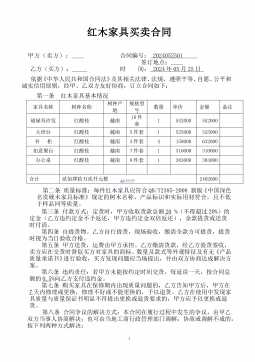

Robert Sheckley - Mindswap

VIP免费

2024-11-29

1

0

416.93KB

108 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

MINDSWAP

ROBERT SHECKLEY

PAN BOOKS LTD

LONDON AND SYDNEY

© Robert Sheckley 1966

TO PAUL KWITNEY

CHAPTER 1

Marvin Flynn read the following advertisement in the classified section of the

Stanhope Gazette:

Gentleman from Mars, age 43, quiet, studious, cultured, wishes to

exchange bodies with similarly inclined Earth gentleman. August 1 -

September 1. References exchanged. Brokers protected.

This commonplace announcement was enough to set Flynn's pulse racing. To

swap bodies with a Martian ... It was an exciting idea, but also a repellent one.

After all, no one would want some sand-grubbing old Martian inside his head,

moving his arms and legs, looking out of his eyes and listening with his ears.

But in return for this unpleasantness, he, Marvin Flynn, would be able to see

Mars. And he would be able to see it as it should be seen: through the senses of

a native.

As some wish to collect paintings, others books, others women, so Marvin

Flynn wanted to acquire the substance of them all through travel. But this, his

ruling passion, was sadly unfulfilled. He had been born and raised in Stanhope,

New York. Physically, his town was some three hundred miles from New York

City. But spiritually and emotionally, the two cities were about a hundred years

apart.

Stanhope was a pleasing rural community situated in the foothills of the

Adirondacks, garlanded with orchards and dotted with clusters of brown cows

against rolling green pastureland. Invincibly bucolic, Stanhope clung to antique

ways; amiably, but with a hint of pugnacity. the town kept its distance from the

flinthearted megalopolis to the south. The IRT - 7th Avenue subway had

burrowed upstate as far as Kingston, but no farther. Gigantic freeways twisted

their concrete tentacles over the countryside, but could not take over Stanhope's

elm-lined Main Street. Other communities maintained a blast pit; Stanhope

clung to its antiquated jet field and was content with triweekly service. (Often at

night, Marvin had lain in bed and listened to that poignant sound of a vanishing

rural America, the lonely wail of a jetliner.)

Stanhope was satisfied with itself, and the rest of the world seemed quite

satisfied with Stanhope and willing to leave it to its romantic dream of a less

hurried age. The only person whom the arrangement did not suit was Marvin

Flynn.

He had gone on the usual tours and had seen the usual things. Like everyone

else, he had spent many weekends in the capitals of Europe. And he had

explored the sunken city of Miami by scuba, gazed at the Hanging Gardens of

London, and had worshipped in the Bahai temple in Haifa. For his longer

vacations, he had gone on a walking tour across Marie Byrd Land, explored the

lower Ituri Rain Forest, crossed Sinkiang by camel, and had even lived for

several weeks in Lhassa, the art capital of the world. In all of this, his actions

were typical of his age and station.

But these trips meant nothing to him; they were the usual tourist assortment,

the sort of things that any casual vacationer was likely to do. Instead of rejoicing

in what he had, Flynn complained of what was denied him. He wanted to really

travel, and that meant going extraterrestrial.

It didn't seem so much to ask; and yet, he had never even been to the Moon.

In the final analysis, it was a matter of economics. Interstellar travel was

expensive; for the most part, it was confined to the rich, or to colonists and

administrators. It was simply out of the question for an average sort of fellow.

Unless, of course, he wished to avail himself of the advantages of Mindswap.

Flynn, with innate small-town conservatism, had avoided this logical but

unsettling step. Until now.

Marvin had tried to reconcile himself to his position in life, and to the very

acceptable possibilities that that position offered him. After all, he was free, gay,

and thirty-one (a little over thirty-one, actually). He was personable, a tall,

broad-shouldered boy with a clipped black moustache and gentle brown eyes.

He was healthy, intelligent, a good mixer, and not unacceptable to the other sex.

He had received the usual education: grade school, high school, twelve years of

college, and four years of postgraduate work. He was well trained for his job

with the Reyck-Peters Corporation. There he fluoroscoped plastic toys,

subjecting them to stress analysis and examining them for microshrinkage,

porosity, texture fatigue, and the like. Perhaps it wasn't the most important job in

the world; but then, we can't all be kings or spaceship pilots. It was certainly a

responsible position, especially when one considers the importance of toys in

this world, and the vital task of alleviating the frustrations of children.

Marvin knew all this; and yet, he was unsatisfied. In vain he had gone to his

neighbourhood Counsellor. This kindly man had tried to help Marvin through

Situation Factor Analysis, but Marvin had not responded with insight. He

wanted to travel, he refused to look honestly at the hidden implications of that

desire, and he would not accept any substitutes.

And now, reading that mundane yet thrilling advertisement similar to a

thousand others yet unique in its particularity (since he was at the moment

reading it), Marvin felt a strange sensation in his throat. To swap bodies with a

Martian ... to see Mars, to visit the Burrow of the Sand King, to travel through

the aural splendour of The Wound, to listen to the chromatic sands of the Great

Dry Sea ...

He had dreamed before. But this time was different. That strange sensation in

his throat argued a decision in the forming. Marvin wisely did not try to force it.

Instead, he put on his beanie and went downtown to the Stanhope Pharmacy.

CHAPTER 2

As he had expected, his best friend, Billy Hake, was at the soda fountain, sitting

on a stool and drinking a mild hallucinogen known as an LSD frappé.

'How's the morn, Sorn?' Hake asked, in the slang popular at that time.

'Soft and mazy, Esterhazy,' Marvin replied, giving the obligatory response.

'Du koomen ta de la klipje?' Billy asked. (Pidgin Spanish-Afrikaans dialect

was the new laugh sensation that year.)

'Ja, Mijnheer,' Marvin answered, a little heavily. His heart simply was not in

the clever repartee.

Billy caught the nuance of dissatisfaction. He raised a quizzical eyebrow,

folded his copy of James Joyce Comics, popped a Keen-Smoke into his mouth,

bit down to release the fragrant green vapour, and asked, 'For-why you burrow?'

The question was wryly phrased but obviously well intended.

Marvin sat down beside Billy. Heavyhearted, yet unwilling to reveal his

unhappiness to his lighthearted friend, he held up both hands and proceeded to

speak in Plains Indian Sign Language. (Many intellectually inclined young men

were still under the influence of last year's sensational Projectoscope production

of Dakota Dialogue, starring Bjorn Rakradish as Crazy Horse and Milovar

Slavovivowitz as Red Cloud, and done entirely in gesture.)

Marvin made the gestures, mocking yet serious, for heart-that-breaks, horse-

that-wanders, sun-that-will-not-shine, moon-that-cannot rise.

He was interrupted by Mr Bigelow, proprietor of the Stanhope Pharmacy. Mr

Bigelow was a middle-aged man of seventy-four, slightly balding, with a small

but evident paunch. Yet he affected boys' ways. Now he said to Marvin. 'Eh,

Mijnheer, querenzie tomar la klopje inmensa de la cabeza vefrouvens in forma

de ein skoboldash sundae?'

It was typical of Mr Bigelow and others of his generation to overdo the

youthful slang, thus losing any comic effect except the pathetically

unintentional.

'Schnell,' Marvin said, putting him down with the thoughtless cruelty of

youth.

'Well, I never,' said Mr Bigelow, and moved huffily away with the mincing

step he had learned from the Imitation of Life show.

Billy perceived his friend's pain. It embarrassed him. He was thirty-four, a

year and a bit older than Marvin, nearly a man. He had a good job as foreman of

Assembly Line 23 in Peterson's Box Factory. He clung to adolescent ways, of

course, but he knew that his age presented him with certain obligations. Thus, he

cross-circuited his fear of embarrassment, and spoke to his oldest friend in clear.

'Marvin - what's the matter?'

Marvin shrugged his shoulder, quirked his mouth, and drummed aimlessly

with his fingers. He said, 'Oiga, hombre, ein Kleinnachtmusik es demasiado,

nicht wahr? The Todt you ruve to touch . . .'

'Straighten it,' Billy said, with a quiet dignity beyond his years.

'I'm sorry,' Marvin said, in clear. 'It's just - oh, Billy, I really do want to travel

so badly!'

Billy nodded. He was aware of his friend's obsession. 'Sure,' he said. 'Me

too.'

'But not as bad. Billy - I got the burns.'

His skoboldash sundae arrived. Marvin ignored it, and poured out his heart to

his lifelong friend, 'Mira, Billy, it's really got me wound tighter than a plastic

retriever coil. I think of Mars and Venus, and really faraway places like

Aldeberan and Antares and - I mean, gosh, I just can't stop thinking about it all.

Like the Talking Ocean of Procyon IV, and the tripartritate hominoids of Allua

II, and it's like I'll simply die if I don't really and actually see those places.'

'Sure,' his friend said. 'I'd like to see them, too.'

'No, you don't understand,' Marvin said. 'It's not just to see - it's - it's like -

it's worse than - I mean, I can't just live here in Stanhope the rest of my life even

though it's fun and I got a nice job and I'm dating some really guapa girls but

heck, I can't just marry some girl and raise kids and - and - there's gotta be

something more!'

Then Marvin lapsed into adolescent incoherence. But something of his

feelings had come through the wild torrent of his words, and his friend nodded

sagely.

'Marvin,' he said softly, 'I read you five by five, honest to Sam I do. But gee,

even interplanetary travel costs fortunes. And interstellar stuff is just plain

impossible.'

'It's all possible,' Marvin said, 'if you use Mindswap.'

'Marvin! You can't mean that!' His friend was too shocked to avoid the

exclamation.

'I can!' Marvin said. 'And by the Christo malherido, I'm going to!'

That shocked them both. Marvin hardly ever used bad language, and his

friend could see the considerable stress he was under to use such an expression,

even though coded. And Marvin, having said what he had said, recognized the

implacable nature of his resolve. And having expressed it, he found it less

frightening to contemplate the next step, that of doing something about it.

'But you can't,' Billy said. 'Mindswap is - well, it's dirty!'

' "Dirty he who dirty thinks, Cabrón." '

'No, seriously. You don't want some sand-grubbing old Martian inside your

head? Moving your legs and arms, looking out of your eyes, touching you, and

maybe even--'

Marvin cut him off before he said something really bad. 'Mira,' he said,

'recuerda que I'll be in his body, on Mars, so he'll be having the same

embarrassments.'

'Martians haven't got no sense of embarrassment,' Billy said.

'That's just not true,' Marvin said. Although younger, he was in many ways

more mature than his friend. He had been an apt student in Comparative

Interstellar Ethics. And his intense desire to travel rendered him less provincial

in his attitudes, more prepared to see the other creature's point of view, than his

friend. From the age of twelve, when he had learned how to read, Marvin had

studied the manners and modes of many different races in the galaxy. Always he

had endeavoured to view those creatures through their own eyes, and to

understand their motivations in terms of their own unique psychologies.

Furthermore, he had scored in the 95th percentile in Projective Empathy, thus

establishing his raw potentiality for successful extraterrestrial relationships. In a

word, he was as prepared for travel as it is possible for a young man to become

who has lived all his life in a small town in the hinterlands of Earth.

That afternoon, alone in his attic room, Marvin opened his encyclopedia. It had

been his companion and friend ever since his parents bought it for him when he

was nine. Now he set the comprehension level at 'simple', the scan rate at 'rapid',

punched his questions, and settled back as the little red and green lights flashed

on.

'Hi, fellows,' the tapecorder said in its fruitily enthusiastic voice. 'Today -

let's talk about Mindswap!'

There followed a historical section, which Marvin ignored. His attention

returned when he heard the tapecorder saying:

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

MINDSWAPROBERTSHECKLEYPANBOOKSLTDLONDONANDSYDNEY©RobertSheckley1966TOPAULKWITNEYCHAPTER1MarvinFlynnreadthefollowingadvertisementintheclassifiedsectionoftheStanhopeGazette:GentlemanfromMars,age43,quiet,studious,cultured,wishestoexchangebodieswithsimilarlyinclinedEarthgentleman.August1-September1.Refe...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:108 页

大小:416.93KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-11-29

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394