Seite 2 ZEP 23. Jg. Heft 3 September 2000

David Selby

Global Education as

Transformative

Education

Zusammenfassung: David Selby stellt ein Modell Globa-

len Lernens, das von vier Säulen getragen wird. Globale

Erziehung im Sinne Selbys vollzieht sich nicht allein durch

die Beschäftigung mit globalen ökologischen oder ökono-

mischen Problemen, sondern muss von einer grundlegenden

Veränderung unseres (industriellen) reduktionistischen

Blickwinkels und Bewusstseins - hin zu einem holistischen

Selbstverständnis begleitet werden.

Varieties of Global Education

Towards the close of the first regional conference on Glo-

bal Education organised by UNICEF MENA (Middle East

and North Africa) and held at Broumana, Lebanon, in July

1995, I was asked, as conference consultant, to prepare a

short notice a transparency conveying the essence of global

education. For better or worse, I presented delegates with the

following:

Global education is an holistic paradigm of education

predicated upon the interconnectedness of communities,

lands, and peoples, the interrelatedness of all social, cultural

and natural phenomena, the interpenetrative nature of past,

present and future, and the complementary nature of the

cognitive, affective, physical and spiritual dimensions of

the human being. It addresses issues of development, equity,

peace, social and environmental justice, and environmental

sustainability. Its scope encompasses the personal, the local,

the national and the planetary. Congruent with its precepts

and principles, its pedagogy is experiential, interactive,

children-centred, democratic, convivial, participatory, and

change-oriented.

It needs to be made clear at the outset that there are multi-

ple interpretations and many varieties of global education

and that the term has experienced the same kind of "semantic

inflation" that has beset terms such as "sustainable

development" and "sustainability" (Sauvé 1999). For some,

global education is akin to a world affairs course in a high

school curriculum, offering an all-too-rare timetable slot for

students to consider global issues and international relations

in a systematic way (Heater 1980). For others, it is a project

to infuse the social studies curriculum particularly, but not

exclusively, at intermediate and senior grades with a "global

perspective" (Petrie 1992; Werner/Case 1997). Significantly

the national vehicle for the promotion of global education

in the U.S.A. is the National Council for the Social Sciences.

For yet others, global education seeks to promote the study

of global issues and themes, such as sustainable futures, qua-

lity of life, conflict and security, and social justice, across

the curriculum within an integrated, interdisciplinary or trans-

disciplinary framework (Lyons 1992). Implicitly, or in some

cases explicitly, the "buck" stops at the curriculum (and its

associated learning and teaching methodologies). A further

school of thought, in which I include myself, argues that

global education is nothing less than the educational ex-

pression of an ecological, holistic or systemic paradigm

(Capra 1996; Capra/Steindl-Rast 1992) and, as such, has

implications for the nature, purposes, and processes of

learning and for every aspect of the functioning of a school

or other learning community (Selby 1999, 2000; Pike/ Selby,

forthcoming).

If, within the fabric of the global education debate,

differences regarding scope provide the warp of the argument,

the weft concerns ideology, goals and purposes. There are

those who perceive purpose in terms of increasing competi-

tiveness, reinforcing dominance and buttressing decline

within the global marketplace. The Illinois State Board of

Education document, Increasing International and

Intercultural Competence through Social Sciences, for

instance, speaks of the need to equip students for effective

participation in a world in which it is necessary to "court

foreign investors and markets for locally produced goods"

and Toh Swee-Hin (1993) has noted a similar commercial

strategic argument in some Canadian global education

mission statements. Knowing about global interdependen-

cies, (some) global issues, and other cultures will thus increase

"global competitiveness". Such a position is, perhaps, the

baldest manifestation of the "liberal-technocratic" paradigm

of global education within which global interdependencies

are viewed uncritically (i.e. as symmetrical), culture is treated

fragmentally and superficially rather than holistically and

paradigmatically, and a management interpretation of the

"global village", with its reliance on experts and elites, is

overtly or covertly embraced (Toh 1993). Set against this is

a "transformative paradigm" of global education which is

"explicitly ethical", encourages a critical global literacy

(interdependencies at all levels viewed as preponderantly

asymmetrical), highlights the "pervasive reality of structural

violence", embraces a radical pedagogy, and is liberationist,

empowering and ecological (Toh 1993, p. 11-14). Another

divide of significance that has recently opened up within

the field is between those whose work is (often uncritically)

humanistic in tone and assumptions, and those calling for

biocentric expressions of global education in which the hu-

man project is decentered (Pike 1996/Selby 1995). The glo-

bal education I want to discuss here is of the biocentric,

holistic, and transformative genre.

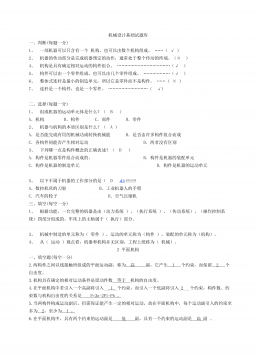

A Four-Dimensional Model of Global Education

I would like to propose a four-dimensional model for glo-

bal education. The model comprises three outer dimensions

and an inner dimension, reflecting the global educator's twin

2024-11-15 27

2024-11-15 27

2024-11-15 16

2024-11-15 16

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 7

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 6

2025-04-07 6

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 8

2025-04-07 11

2025-04-07 11

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394