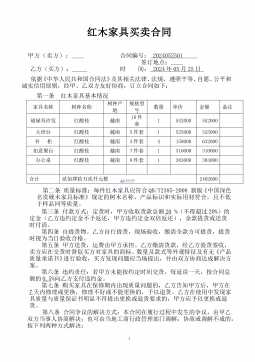

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING(称王的记者)

VIP免费

2024-12-26

2

0

171.94KB

44 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

1

THE REPORTER WHO

MADE HIMSELF KING

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

2

The Old Time Journalist will tell you that the best reporter is the one

who works his way up. He holds that the only way to start is as a

printer's devil or as an office boy, to learn in time to set type, to graduate

from a compositor into a stenographer, and as a stenographer take down

speeches at public meetings, and so finally grow into a real reporter, with a

fire badge on your left suspender, and a speaking acquaintance with all the

greatest men in the city, not even excepting Police Captains.

That is the old time journalist's idea of it. That is the way he was

trained, and that is why at the age of sixty he is still a reporter. If you

train up a youth in this way, he will go into reporting with too full a

knowledge of the newspaper business, with no illusions concerning it, and

with no ignorant enthusiasms, but with a keen and justifiable impression

that he is not paid enough for what he does. And he will only do what he

is paid to do.

Now, you cannot pay a good reporter for what he does, because he

does not work for pay. He works for his paper. He gives his time, his

health, his brains, his sleeping hours, and his eating hours, and sometimes

his life, to get news for it. He thinks the sun rises only that men may

have light by which to read it. But if he has been in a newspaper office

from his youth up, he finds out before he becomes a reporter that this is

not so, and loses his real value. He should come right out of the

University where he has been doing "campus notes" for the college

weekly, and be pitchforked out into city work without knowing whether

the Battery is at Harlem or Hunter's Point, and with the idea that he is a

Moulder of Public Opinion and that the Power of the Press is greater than

the Power of Money, and that the few lines he writes are of more value in

the Editor's eyes than is the column of advertising on the last page, which

they are not.

After three years--it is sometimes longer, sometimes not so long--he

finds out that he has given his nerves and his youth and his enthusiasm in

exchange for a general fund of miscellaneous knowledge, the opportunity

of personal encounter with all the greatest and most remarkable men and

events that have risen in those three years, and a great fund of resource

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

3

and patience. He will find that he has crowded the experiences of the

lifetime of the ordinary young business man, doctor, or lawyer, or man

about town, into three short years; that he has learned to think and to act

quickly, to be patient and unmoved when everyone else has lost his head,

actually or figuratively speaking; to write as fast as another man can talk,

and to be able to talk with authority on matters of which other men do not

venture even to think until they have read what he has written with a copy-

boy at his elbow on the night previous.

It is necessary for you to know this, that you may understand what

manner of man young Albert Gordon was.

Young Gordon had been a reporter just three years. He had left Yale

when his last living relative died, and had taken the morning train for New

York, where they had promised him reportorial work on one of the

innumerable Greatest New York Dailies. He arrived at the office at noon,

and was sent back over the same road on which he had just come, to

Spuyten Duyvil, where a train had been wrecked and everybody of

consequence to suburban New York killed. One of the old reporters

hurried him to the office again with his "copy," and after he had delivered

that, he was sent to the Tombs to talk French to a man in Murderers' Row,

who could not talk anything else, but who had shown some international

skill in the use of a jimmy. And at eight, he covered a flower-show in

Madison Square Garden; and at eleven was sent over the Brooklyn Bridge

in a cab to watch a fire and make guesses at the losses to the insurance

companies.

He went to bed at one, and dreamed of shattered locomotives, human

beings lying still with blankets over them, rows of cells, and banks of

beautiful flowers nodding their heads to the tunes of the brass band in the

gallery. He decided when he awoke the next morning that he had entered

upon a picturesque and exciting career, and as one day followed another,

he became more and more convinced of it, and more and more devoted to

it. He was twenty then, and he was now twenty-three, and in that time

had become a great reporter, and had been to Presidential conventions in

Chicago, revolutions in Hayti, Indian outbreaks on the Plains, and

midnight meetings of moonlighters in Tennessee, and had seen what work

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

4

earthquakes, floods, fire, and fever could do in great cities, and had

contradicted the President, and borrowed matches from burglars. And

now he thought he would like to rest and breathe a bit, and not to work

again unless as a war correspondent. The only obstacle to his becoming

a great war correspondent lay in the fact that there was no war, and a war

correspondent without a war is about as absurd an individual as a general

without an army. He read the papers every morning on the elevated

trains for war clouds; but though there were many war clouds, they always

drifted apart, and peace smiled again. This was very disappointing to

young Gordon, and he became more and more keenly discouraged.

And then as war work was out of the question, he decided to write his

novel. It was to be a novel of New York life, and he wanted a quiet place

in which to work on it. He was already making inquiries among the

suburban residents of his acquaintance for just such a quiet spot, when he

received an offer to go to the Island of Opeki in the North Pacific Ocean,

as secretary to the American consul at that place. The gentleman who

had been appointed by the President to act as consul at Opeki was Captain

Leonard T. Travis, a veteran of the Civil War, who had contracted a severe

attack of rheumatism while camping out at night in the dew, and who on

account of this souvenir of his efforts to save the Union had allowed the

Union he had saved to support him in one office or another ever since.

He had met young Gordon at a dinner, and had had the presumption to ask

him to serve as his secretary, and Gordon, much to his surprise, had

accepted his offer. The idea of a quiet life in the tropics with new and

beautiful surroundings, and with nothing to do and plenty of time in which

to do it, and to write his novel besides, seemed to Albert to be just what he

wanted; and though he did not know nor care much for his superior officer,

he agreed to go with him promptly, and proceeded to say good-by to his

friends and to make his preparations. Captain Travis was so delighted

with getting such a clever young gentleman for his secretary, that he

referred to him to his friends as "my attache of legation;" nor did he lessen

that gentleman's dignity by telling anyone that the attache's salary was to

be five hundred dollars a year. His own salary was only fifteen hundred

dollars; and though his brother-in-law, Senator Rainsford, tried his best to

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

5

get the amount raised, he was unsuccessful. The consulship to Opeki

was instituted early in the '50's, to get rid of and reward a third or fourth

cousin of the President's, whose services during the campaign were

important, but whose after-presence was embarrassing. He had been

created consul to Opeki as being more distant and unaccessible than any

other known spot, and had lived and died there; and so little was known of

the island, and so difficult was communication with it, that no one knew

he was dead, until Captain Travis, in his hungry haste for office, had

uprooted the sad fact. Captain Travis, as well as Albert, had a secondary

reason for wishing to visit Opeki. His physician had told him to go to

some warm climate for his rheumatism, and in accepting the consulship

his object was rather to follow out his doctor's orders at his country's

expense, than to serve his country at the expense of his rheumatism.

Albert could learn but very little of Opeki; nothing, indeed, but that it

was situated about one hundred miles from the Island of Octavia, which

island, in turn, was simply described as a coaling-station three hundred

miles distant from the coast of California. Steamers from San Francisco

to Yokohama stopped every third week at Octavia, and that was all that

either Captain Travis or his secretary could learn of their new home.

This was so very little, that Albert stipulated to stay only as long as he

liked it, and to return to the States within a few months if he found such a

change of plan desirable.

As he was going to what was an almost undiscovered country, he

thought it would be advisable to furnish himself with a supply of articles

with which he might trade with the native Opekians, and for this purpose

he purchased a large quantity of brass rods, because he had read that

Stanley did so, and added to these, brass curtain-chains, and about two

hundred leaden medals similar to those sold by street pedlers during the

Constitutional Centennial celebration in New York City.

He also collected even more beautiful but less exensive decorations for

Christmas-trees, at a wholsesale house on Park Row. These he hoped to

exchange for furs or feathers or weapons, or for whatever other curious

and valuable trophies the Island of Opeki boasted. He already pictured

his rooms on his return hung fantastically with crossed spears and

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

6

boomerangs, feather head-dresses, and ugly idols.

His friends told him that he was doing a very foolish thing, and argued

that once out of the newspaper world, it would be hard to regain his place

in it. But he thought the novel that he would write while lost to the world

at Opeki would serve to make up for his temporary absence from it, and he

expressly and impressively stipulated that the editor should wire him if

there was a war.

Captain Travis and his secretary crossed the continent without

adventure, and took passage from San Francisco on the first steamer that

touched at Octavia. They reached that island in three days, and learned

with some concern that there was no regular communication with Opeki,

and that it would be necessary to charter a sailboat for the trip. Two

fishermen agreed to take them and their trunks, and to get them to their

destination within sixteen hours if the wind held good. It was a most

unpleasant sail. The rain fell with calm, unrelentless persistence from

what was apparently a clear sky; the wind tossed the waves as high as the

mast and made Captain Travis ill; and as there was no deck to the big boat,

they were forced to huddle up under pieces of canvas, and talked but little.

Captain Travis complained of frequent twinges of rheumatism, and gazed

forlornly over the gunwale at the empty waste of water.

"If I've got to serve a term of imprisonment on a rock in the middle of

the ocean for four years," he said, "I might just as well have done

something first to deserve it. This is a pretty way to treat a man who bled

for his country. This is gratitude, this is." Albert pulled heavily on his

pipe, and wiped the rain and spray from his face and smiled.

"Oh, it won't be so bad when we get there," he said; "they say these

Southern people are always hospitable, and the whites will be glad to see

anyone from the States."

"There will be a round of diplomatic dinners," said the consul, with an

attempt at cheerfulness. "I have brought two uniforms to wear at them."

It was seven o'clock in the evening when the rain ceased, and one of

the black, half-naked fishermen nodded and pointed at a little low line on

the horizon.

"Opeki," he said. The line grew in length until it proved to be an

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

7

island with great mountains rising to the clouds, and, as they drew nearer

and nearer, showed a level coast running back to the foot of the mountains

and covered with a forest of palms. They next made out a village of

thatched huts around a grassy square, and at some distance from the

village a wooden structure with a tin roof.

"I wonder where the town is," asked the consul, with a nervous glance

at the fishermen. One of them told him that what he saw was the town.

"That?" gasped the consul. "Is that where all the people on the island

live?"

The fisherman nodded; but the other added that there were other

natives further back in the mountains, but that they were bad men who

fought and ate each other. The consul and his attache of legation gazed at

the mountains with unspoken misgivings. They were quite near now, and

could see an immense crowd of men and women, all of them black, and

clad but in the simplest garments, waiting to receive them. They seemed

greatly excited and ran in and out of the huts, and up and down the beach,

as wildly as so many black ants. But in the front of the group they

distinguished three men who they could see were white, though they were

clothed, like the others, simply in a shirt and a short pair of trousers.

Two of these three suddenly sprang away on a run and disappeared among

the palm-trees; but the third one, when he recognized the American flag in

the halyards, threw his straw hat in the water and began turning

handsprings over the sand.

"That young gentleman, at least," said Albert, gravely, "seems pleased

to see us."

A dozen of the natives sprang into the water and came wading and

swimming toward them, grinning and shouting and swinging their arms.

"I don't think it's quite safe, do you?" said the consul, looking out

wildly to the open sea. "You see, they don't know who I am."

A great black giant threw one arm over the gunwale and shouted

something that sounded as if it were spelt Owah, Owah, as the boat carried

him through the surf.

"How do you do?" said Gordon, doubtfully. The boat shook the giant

off under the wave and beached itself so suddenly that the American

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

8

consul was thrown forward to his knees. Gordon did not wait to pick

him up, but jumped out and shook hands with the young man who had

turned handsprings, while the natives gathered about them in a circle and

chatted and laughed in delighted excitement.

"I'm awfully glad to see you," said the young man, eagerly. "My

name's Stedman. I'm from New Haven, Connecticut. Where are you

from?"

"New York," said Albert. "This," he added, pointing solemnly to

Captain Travis, who was still on his knees in the boat, "is the American

consul to Opeki." The American consul to Opeki gave a wild look at Mr.

Stedman of New Haven and at the natives.

"See here, young man," he gasped, "is this all there is of Opeki?"

"The American consul?" said young Stedman, with a gasp of

amazement, and looking from Albert to Captain Travis. "Why, I never

supposed they would send another here; the last one died about fifteen

years ago, and there hasn't been one since. I've been living in the

consul's office with the Bradleys, but I'll move out, of course. I'm sure

I'm awfully glad to see you. It'll make it so much more pleasant for me."

"Yes," said Captain Travis, bitterly, as he lifted his rheumatic leg over

the boat; "that's why we came."

Mr. Stedman did not notice this. He was too much pleased to be

anything but hospitable. "You are soaking wet, aren't you?" he said; "and

hungry, I guess. You come right over to the consul's office and get on

some other things."

He turned to the natives and gave some rapid orders in their language,

and some of them jumped into the boat at this, and began to lift out the

trunks, and others ran off toward a large, stout old native, who was sitting

gravely on a log, smoking, with the rain beating unnoticed on his gray

hair.

"They've gone to tell the King," said Stedman; "but you'd better get

something to eat first, and then I'll be happy to present you properly."

"The King," said Captain Travis, with some awe; "is there a king?"

"I never saw a king," Gordon remarked, "and I'm sure I never expected

to see one sitting on a log in the rain."

THE REPORTER WHO MADE HIMSELF KING

9

"He's a very good king," said Stedman, confidentially; "and though

you mightn't think it to look at him, he's a terrible stickler for etiquette and

form. After supper he'll give you an audience; and if you have any

tobacco, you had better give him some as a present, and you'd better say

it's from the President: he doesn't like to take presents from common

people, he's so proud. The only reason he borrows mine is because he

thinks I'm the President's son."

"What makes him think that?" demanded the consul, with some

shortness. Young Mr. Stedman looked nervously at the consul and at

Albert, and said that he guessed someone must have told him.

The consul's office was divided into four rooms with an open court in

the middle, filled with palms, and watered somewhat unnecessarily by a

fountain.

"I made that," said Stedman, in a modest, offhand way. "I made it out

of hollow bamboo reeds connected with a spring. And now I'm making

one for the King. He saw this and had a lot of bamboo sticks put up all

over the town, without any underground connections, and couldn't make

out why the water wouldn't spurt out of them. And because mine spurts,

he thinks I'm a magician."

"I suppose," grumbled the consul, "someone told him that too."

"I suppose so," said Mr. Stedman, uneasily.

There was a veranda around the consul's office, and inside the walls

were hung with skins, and pictures from illustrated papers, and there was a

good deal of bamboo furniture, and four broad, cool-looking beds. The

place was as clean as a kitchen. "I made the furniture," said Stedman,

"and the Bradleys keep the place in order."

"Who are the Bradleys?" asked Albert.

"The Bradleys are those two men you saw with me," said Stedman;

"they deserted from a British man-of-war that stopped here for coal, and

they act as my servants. One is Bradley, Sr., and the other Bradley, Jr."

"Then vessels do stop here occasionally?" the consul said, with a

pleased smile.

"Well, not often," said Stedman. "Not so very often; about once a

year. The Nelson thought this was Octavia, and put off again as soon as

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

THEREPORTERWHOMADEHIMSELFKING1THEREPORTERWHOMADEHIMSELFKINGTHEREPORTERWHOMADEHIMSELFKING2TheOldTimeJournalistwilltellyouthatthebestreporteristheonewhoworkshiswayup.Heholdsthattheonlywaytostartisasaprinter'sdevilorasanofficeboy,tolearnintimetosettype,tograduatefromacompositorintoastenographer,andasas...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:44 页

大小:171.94KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-26

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394