Larry Niven - Man - Kzin Wars 11

VIP免费

2024-12-23

2

0

684.53KB

230 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

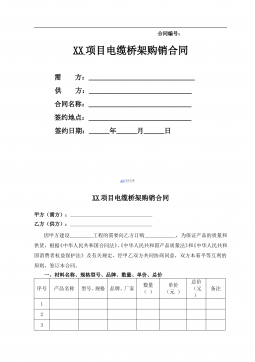

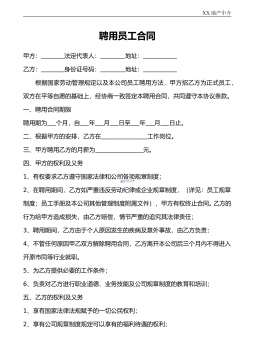

Man-Kzin Wars XI

Table of Contents

THREE AT TABLE

GROSSGEISTER SWAMP

CATSPAWS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

TEACHER'S PET

I

II

III

WAR AND PEACE

THE HUNTING PARK

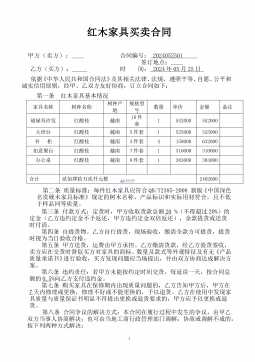

MAN-KZIN WARS XI

HAL COLEBATCH

AND

MATTHEW HARRINGTON

CREATED BY

LARRY NIVEN

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any

resemblance to real people or incidents is purely coincidental.

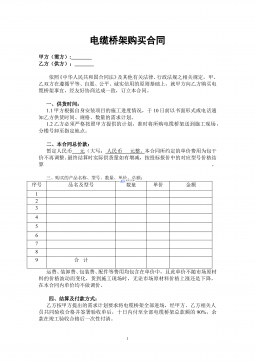

Three at Tablecopyright © 2005 by Hal Colebatch;Grossgeister Swamp by Hal Colebatch;Catspaws

copyright © 2005 by Hal Colebatch;Teacher's Pet copyright © 2005 by Matthew Harrington,War and

Peace copyright © 2005 by Matthew Harrington;The Hunting Park copyright © 2005 by Larry Niven.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

www.baen.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-0906-6

ISBN-10: 1-4165-0906-2

Cover art by Stephen Hickman

First printing, October 2005

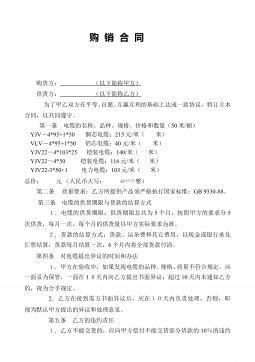

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Man-Kzin wars XI / Hal Colebatch and Matthew Harrington ; created by Larry Niven.

p. cm.

Three at table / Hal Colebatch — Grossgeister Swamp / Hal Colebatch — Catspaws / Hal Colebatch

— Teacher's pet / Matthew J. Harrington — War and peace / Matthew J. Harrington — The hunting

park / Larry Niven.

ISBN 1-4165-0906-2 (hc)

1. Science fiction, American. 2. Kzin (Imaginary place)—Fiction. 3. Science fiction, Australian. 4. Space

warfare—Fiction. 5. War stories, Australian. 6. War stories, American. I. Title: Man-Kzin wars 11. II.

Title: Man-Kzin wars eleven. III. Colebatch, Hal, 1945- IV. Harrington, Matthew J. V. Niven, Larry.

PS648.S3M3753 2005

813'.0876208—dc22

2005019121

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Produced & designed by Windhaven Press, Auburn, NH (www.windhaven.com)

Printed in the United States of America

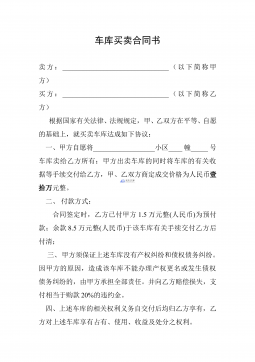

THE MAN-KZIN WARS SERIES

Created by Larry Niven

The Man-Kzin Wars

The Houses of the Kzinti

Man-Kzin Wars V

Man-Kzin Wars VI

Man-Kzin Wars VII

Choosing Names: Man-Kzin Wars VIII

Man-Kzin Wars IX

Man-Kzin Wars X: The Wunder War

Man-Kzin Wars XI

The Best of All Possible Wars

Also by Larry Niven

Fallen Angels(with Jerry Pournelle & Michael Flynn)

Three At Table

Hal Colebatch

To the memory of W. W. Jacobs

Arthur Guthlac, Wunderland, 2427 a.d.

I've been stupid, I thought. Being stupid on a strange planet is very often an effective way to be dead.

Even a planet as friendly to Man as Wunderland.

Stupid to go through fifty-three years of desperate war to die on Wunderland seven years after

Liberation in a bad storm, on a leave I've spent a long time looking forward to.

But maybe I won't die, I told myself then as the mud fell and slid about me.Maybe I'll look back on all

this one day and laugh. I've been in far worse places and survived. Keep climbing, disregard my

ankle and get above the flood-mark. Then climb higher. I didn't know then what I was climbing into.

* * *

I had set out from Gerning in an air-car for a day's lone hunting in the wilder country to the east. I hadn't

brought much in the way of food or clothes or even weapons. What's the point of a hunt with modern

gear that gives the game animals no chance? You might as well zap them by laser with the aid of a

satellite camera. I had an antique .22 rifle and a box of bullets and a handy little device copied from the

kzin trophy-drier for anything I wanted to freeze-dry and bring home.

There was a good autodoc in the air-car, of course, and a modern communication system. My

headquarters could get in touch with me, and I with them, at any time. I hoped they wouldn't.

A long, long time ago, I had been a museum guard on Earth. I had worn a quaint uniform and collected

banned scraps of militaria and had also dreamed of exploring distant worlds—had hoped more

realistically that with some saving and luck I might one day get a budget package holiday to the Moon to

remember for the rest of my life like some of my lucky fellows on the museum general staff. There had

been notions of glory and heroism, too remote, too impossible even to be called dreams, barely possible

to hint at even to my sister, the one human with whom I had in those days confided. Now, if I wore

uniform, it was different and had a star on the collar. But, more importantly for me at that moment, I had

humanity's first interstellar colony to make free with as a conqueror—well, as a Liberator, certainly—and

I didn't want to waste the experience.

A pity nobody at Gerning had told me about the weather. Apparently—that is the most charitable

explanation—it had never occurred to them that even a holidaying flatlander would be so ignorant or

stupid as not to know what those black-and-silver clouds building up in the west meant. The ramscoop

raid from Sol by the UNSN seven or eight years ago, shortly before the Liberation, had, it was said, as

well as causing terrible damage, upset the patterns of the weather. Storms in the storm-belt came earlier

and stronger. Something to do with the cooling and droplet-suspension effects of dust in the air. It was

expected that things would return to normal eventually. As I had been preparing to depart my hosts had

been more interested in laughing at a funny little thing called a Protean that had turned up in the

meeting-hall, a quaint and harmless Wunderland animal which had evolved limited powers of psi

projection and mimicry. That there were less harmless ones with psi powers I was to find out shortly.

Anyway, the clouds built slowly, and, like a cunning enemy, they gathered out of the west, behind me. I

took off near noon and three-quarters of the sky was clear. I flew low, not at even near full speed, over

the farmlands and woods, fascinated as always by what I saw below. Much of the time I left the car on

auto-pilot, and enjoyed being a rubber-necking tourist. With the kzin-derived gravity-motor, so much

more efficient than our old ground-effect lifts, I could vary the speed and height with the touch of a finger

on the controls. The car gave me a meal, and the day turned into afternoon.

I passed over human farms and little scattered villages and hamlets. The simple dwellings of people living

simple lives, far away from much government and from much of the twenty-fifth century. I knew many of

these people had originally settled here with the simple life in mind, but then the war and kzin occupation

had knocked their technology way back into the past anyway. Some of these settlements were again

prosperous, pleasant-looking places from the air, but there were some desolate ruins, relics of the war

and the occupation that had halved the human population of this planet. I passed over the scattered

wreckage of destroyed war-machines and the kzin base, and the great tracts that the kzinti had had go

back to wilderness as hunting preserves. Humans had often enough been the victims set running

hopelessly in those hunts . . . Many more had died under the kzinti in other ways.

But ghastliness was relative. The Gerning district had largely survived. After the first hideous butcheries

the local humans had learnt kzin ways, and their survival-rate had increased. They humbly avoided

contact with their overlords, abased themselves when they encountered them, and sweated on

diminishing land with deteriorating equipment to raise the various taxes that were the price of life. The

local kzinti, many attached to the big military base, had, apparently, not been quite like the creatures of

the dreadful Lord Ktrodni-Stkaa, and the local Herrenmann had been able to intercede with their

commanding officer occasionally. I had gathered that there were a few kzinti still living in remote bits of

the black-blocks around the area now, as well as solitude-seeking, eccentric or misfit humans.

Wunderland was sparsely enough populated that anyone who wished to be left alone could be.

There were herds of cows and sheep passing below. On Earth I'd never seen them free-ranging like this.

Wunderland creatures, too. There were a herd of gagrumphers, the big, six-legged things that occupied

an ecological niche similar to that of bison or elephants on Earth, moving in and out of the marvellous

multicolored foliage, red and orange and green. Then the human settlements thinned out, and I was

passing over forest again, and uneven ground with a pattern of gullies and water-courses below me, small

rivers low at the end of summer like silver ribbons. The roads were few and narrow.

This was what I had once dreamed of: the landscape below me could never be taken for Earth. Every

color and contour was different, some things slightly and subtly off, some grossly strange. And ahead of

me as I flew, on the eastern horizon, were the tall spires and pinnacles of great mountains,

low-gravity-planet mountains sharper and higher than anything Earth had to show, pale and almost surreal

against the blue and pink tints of the eastern sky.

I should have noticed how quickly it was getting dark. But there, below me, was something else: a

tigripard, the biggest felinoid—the biggestnative felinoid—predator in this part of Wunderland. Their

numbers had built up during the kzin occupation, partly because of the general chaos and desolation, and

also because the kzinti found their fellow-felinoids rather good sport in the hunt and encouraged them,

and they remained a nuisance for these backwoods farmers with their still relatively primitive appliances

and equipment. What modern machinery the kzinti had not smashed or confiscated during the war had

largely become inoperative through lack of maintenance and the farmers were in many cases beginning

again from Square One. I saw some ancient farming robots sprawled broken like the corpses of living

things or, on one long-abandoned farmstead, jerking and grubbing uselessly through degraded

programmes that no longer made sense. The further one got from Gerning the fewer the little farms and

cottages were and the more backward they looked. Nothing like Earth farms.

The tigripard was a big one, worth a hunter's attention. But there was no sport or achievement in

shooting it from above. I followed it for a time, not approaching close enough to alarm it. That was

difficult. I guessed that in the last few decades all Wunderland creatures had become only too alert to

terror and destruction from the air. The tigripard was running down a long slope to lower-lying,

river-dissected, territory. A moving map on the instrument-panel gave me a general picture. I saw it leap

a river—a big leap, but the river was low. The human settlements were much sparser in this area but

there were still a few and there was still quite good grazing for animals. The locals should thank me for

ridding them of a dangerous piece of vermin, I thought. There was very little legal hunting on Earth—even

a UNSN general would find it hard to get a permit there—and I was a completely inexperienced hunter.

At least of things like this.

We were approaching a more deeply gullied, poorly vegetated area like a small badlands. The tigripard

turned into a gully and tracking it became more difficult. After a time I landed and, hefting my little rifle,

followed on foot.

That was the first first stupid thing: I was so used to military sidearms that could bring down a kzin or a

building, that sought their own targets, and could be used like hoses against kzin infantry if necessary, that

I took it for granted the .22 was all I needed. Another stupid thing: I was so used to thinking of my alien

enemies as eight-to-ten-feet-tall bipedal felines or blips on a radar screen that I found it hard to think of a

feline the size of a tigripard—even a big tigripard—as dangerous to me personally. It was quite a long

descent to the watercourse at the bottom. There was a small game-track at first but that petered out. The

gully's walls gradually rose above me, reducing my view of the sky.

I scrambled down to the bed of the watercourse, jumping easily further and further down in the low

gravity, looking for tracks in the damp sand and mud beside the stream. There were none. I pressed on,

into the next gully, almost like a small canyon. It wound and twisted and still the mud yielded nothing. I

was practicing my tracking skills when two things happened: the tigripard leapt up onto a rock in front of

me, snarling, and the sky turned black.

I've had plenty of infantry training, even if quite a while ago. I brought the gun up fast and fired. In that

space its report was ridiculously small, swallowed up by the air around. The tigripard was faster. If it had

gone for me I should probably have died under its claws then and there. But evidently it was experienced

enough to be wary of Man, or at least of Man plus weapons. It leapt sideways and disappeared behind

the gully slope. Whether I hit it or not I had no idea. And at that second I had other things on my mind.

I had never seen a daytime sky turn midnight black before, and the light die in an instant. Who has?

Wunderlanders who live in the storm-belt have, I discovered.

Then the rain and lightning came, the rain in solid sheets, the lightning hardly less unbroken. Thunder filled

and shook the sky. I had seen the sky of Wunderland purple in the light of Alpha Centauri B, one of the

great sights of Human Space. This flaring, vivid purple light was a different thing. In an instant I was

soaked with freezing rain, my head was ringing and I was almost blinded. That's when I heard the tigripad

again.

The tigripard knew Wunderland better than I. But it made the mistake of snarling its challenge before it

leapt. I dropped flat as I fired again and its leap carried it over me. It was a very near thing, though: a

hind-claw shredded the light shirt I was wearing. Below me the ground gave way, and I rolled down a

steep incline. I fetched up bruised and dazed at the bottom. Had it not been for Wunderland's light

gravity I would have been a lot worse off. And the tigripard and the fall had saved my life. As I got

groggily to my feet again a bolt of lightning struck the place I been standing a few moments before. I saw

rocks and earth hurled into the air, and then for a while I might have been blinded.

I could only hope the tigripard was at least temporarily blinded too, but I heard it snarling somewhere

not far away. The skyline had become near and narrow and lightning was trickling all around it. There

were the lashing hailstones, too. Any bigger and they would do real damage. Flicking my rifle back and

forth, trying to cover all directions at once, I ran, still part blind, running straight into cliff faces, stumbling

and falling to a ground that the cloudburst had already churned to mud, boiling up like soup. Live soup,

too. I saw creatures like the froggolinas and kermitoids, I supposed long encased in it, springing to life

and away. Three times I thought I saw movement that might have been the tigripard and fired at it. The

fourth time I heard a snarling, very close, and knew there could be no mistake. But my rifle was so slick

with water and mud, and my hands so cold in the sudden rain and hail, that the selector must have moved

to automatic setting. I fired off all the rest of the magazine in an instant.

I groped for the box of cartridges. Had I brought it with me or left it in the car? I couldn't remember, but

a frantic search showed I didn't have it now. If it had been in my pocket I had lost it in the fall.

I've studied many disasters. I know the worst of them usually don't have a single cause. They are an

accumulation of small things, too small to guard against: a weather or meteor report misfiled by a tired

duty officer, an alarm system not checked one day as it has been every day for years, a faucet blocked

by paint, a decimal point shifted one place in a computer's instructions, a fleck of dust working its way

into an old keyboard . . . I had got where I was in those gullies by an accumulation of small things, and, I

realized quite suddenly, my life was in danger.

So far I had been excited, keyed-up, furious. Suddenly I felt cold and frightened: not the fear of battle,

but another kind of dread. Not only from the tigripard, which seemed to have gone, perhaps hit, though I

doubted that, perhaps to stalk me from cover, but from this rain. Great chunks of earth turned suddenly

to mud were falling from the gully banks and I realized I could end up underneath one. But there was a

more inevitable peril. One thing I know something about is the theory of terrain, and recalling what I had

seen from the air, I knew these canyons must flash-flood in rain like this. I realized that I had seen

high-water-marks in them, all well above where I was now. In fact, I thought, that was probably why the

tigripard was gone. It was climbing, and if I was to remain alive I had better do the same fast.

I slung the rifle over my shoulder and started up the slope. It was hard to make much out in the

ceaselessly-rolling thunder and the constant beating of the hailstones but I thought I could feel the ground

as well as the air shaking. I was so covered in the mud I squirmed through, and in ice from the hailstones,

that perhaps even the superb sensory equipment of the tigripard was confused and could not find me.

There was another thing I remembered: tigripards, though among the most obvious, were by no means

the only Wunderland animals I had to fear. Among other things, very relevant at this moment, there was

the mud-sucker, a thing vaguely like a giant leech, which, I had been told on the orientation course I was

now remembering, could lie dormant in mud, like this, for a long time and then come to life in rain, like

this rain. Apparently its prey included large animals, perhaps up to human size. "No one knows how big

they can grow," the instructor had said. "But don't be the one to find out." Rykermann had also told me

that, like much other Wunderland fauna, little was known about them. They gave cryptic hints of some

kind of dim psi ability, and he too was definite that it was best to keep out of their way.

Another nasty thought: some of the wrecked war-craft which I had flown over on my way here had had

nuclear engines. Could spilled radioactives have worked their way into this mud over the last seven

years? Of course the car had instruments that could have told me at once.

Then the real floods came. Out of the west, and concentrating my mind. The rain must have been falling

there and filling these water-courses long before the storm reached me. A real roaring and shaking of the

ground and white-foam-fronted black water below me advancing like a wall. Hydraulic damming—I

remembered the phrase from somewhere as I scrabbled upwards for my life in the slipping mud. I slipped

and rolled again, ending up caught in a clump of sharp black rocks just above the rising water. I had

damaged my leg some months before in the caves, but it had been healed. Now I felt it was gone again,

in a different place, near the ankle. Maybe (I prayed) not broken this time. One small mercy: crawling,

almost swimming vertically, up the mud-slope in the hail, an ankle was perhaps less crucial than when

walking or running. Another mercy was the low gravity. But progressing up was very different from my

carefree jumping downwards. Anyway, I got to a ridge. I tried to stand then, and found I couldn't. The

.22 made a sort of crutch, not very handy for it was the wrong length and either barrel or stock sank into

the mud when I leaned on it. I more-or-less hopped a few yards.

I had to get back to the car. And then I realized I had not the faintest idea in which direction the car was.

I sat down in the mud and hail then, cursing feebly that I hadn't had the sense even to slip a modern

cover-all into one of my pockets. It would have weighed next to nothing, taken up no space and would, if

I had needed it, kept me as dry and warm as toast. It would even have been strong enough to protect me

in a fight. I had put on locally made clothes for the sake of fresh air and ventilation on a warm morning, as

well as because it was one of the things tourists do.

There were a lot of other things, which, if not misled by the benign appearance of the morning and my

own excitement and inexperience of this world, I might also have brought: a gyro-compass, a locator, a

beacon, even an ordinary mobile telephone, not to mention real weapons. I had plenty of navigation

instruments and communications equipment, as I had a good autodoc and almost everything else I might

need, but they were all in the car. I had an implant by which I could be traced if necessary, but there was

no reason for anyone to think I was in great distress. If anyone was interested and they assumed I had

enough sense to remain with the car and its equipment, then even a storm like this should have been no

problem: a matter of touching a button and closing the canopy.

It took me a long time to make progress, and it horrified me how quickly what little daylight there was

failed.

And the river was still rising. Chunks of mud were sliding and dropping into it from the sides of my ridge.

And the ridge itself was shrinking. Soon it would be an island, and soon after that it would be covered

completely. I would have to climb again. It was then that I fully realized how much my life was in real

danger.

I was alone, lost, injured. And this was not my world. I knew something of its weather and its wild-life in

theory, but I knew that in some ways, simply not having grown up here made me blind and vulnerable to

dangers that others instinctively avoided, blind as a village yokel of the fifteenth century on Earth suddenly

time-transported into a modern city or a modern transport complex. Where was the tigripard? I hardly

dared move now, lest it sense from the pattern of my foot-falls that I was injured and come circling back.

Indeed I feared I was already projecting psi waves to tell it I had changed from hunter to prey. But move

I must. Before I had made much more progress it was full night, or at least the storm's equivalent of it. I

had not appreciated what night was like in the unpeopled country where there was no artificial source of

lighting. The clouds obscured everything in the Wunderland sky above, though far away in the West was

a dim glow that might have been the lights of Gerning reflected against them. Far to the East it was lighter

for a while, but then the clouds covered that as well. The almost incessant lightning was a danger, but

soon it seemed to be my major source of light. It was not full night yet, and when I climbed higher I saw a

distant ribbon of paler sky far to the east still, but full night was coming.

* * *

I climbed again. Glancing back once I saw the black rushing water tear away the last of the ridge where I

had rested. The hailstones tore at its surface and lumped together into chunks of ice.

I knew that I was on what was technically a big island between two rivers, low and narrow when I had

seen them from the air, now both grossly swollen and rising all the time. I recalled seeing houses not far

away. I toiled further up the next sliding muddy slope, again using my weapon as a sort of crutch. It took

me a long time, and my skin crawled as I waited for the impact of the tigripard on my back, and thought

of the irony of dying under the claws of a feline after all. Then at some point the sliding mud became more

stable and solid. My ankle was badly swollen but massaging it seemed to help, and out of the mud I

could walk, slowly and cautiously. The rifle was some more use as a prop here, but I wished it had been

a couple of feet longer. Again I was thankful for Wunderland's light gravity.

Below me, something writhed through the mud up the track I had left. For a moment I thought it was the

tigripard. But as it came closer I saw it was a shapeless thing with a trumpet-like suctorial disk, the orifice

ringed with small fangs and tentacles—a mud-sucker, a big one. I was feeling too battered and numbed

to react for a few seconds, then fear and revulsion set me moving a good deal faster than I would have

thought possible. It didn't like the firmer ground though, and after waving its trumpet in my direction for a

time turned back, vacuuming up some of the newly active froggolinas as it went. I hoped it would find the

tigripard—or did I? The tigripard was a brother compared to this thing, and deserved a cleaner fate.

You can imagine my delight when, as I gained some even higher ground, a burst of lightning showed me

a road at my feet. More importantly, after I had followed this for a while, another burst showed the

unmistakable straight lines of man-made walls and structures some way off. Another two or three flashes

and I made out that there was a small village, a hamlet, I suppose it should be called. A single street and

a few one-story houses. Shelter, warmth, food, help, safety. I hobbled on as fast as I could.

Realization didn't all come at once. First I noticed there were no lights burning. Then in the lightning

flashes I saw roofless skies through gaping holes where windows had been. The hamlet was a deserted

ruin.

If I was bitterly disappointed, I saw that it was still shelter of a sort. I know now why you should keep

out of deserted ruins in this part of Wunderland if you're alone and can't see well, and if you're effectively

unarmed. At that time what I wanted was to get out of the cold driving rain and hailstones at least. And I

wanted a door to keep the tigripard out should it return, or even the sucker-thing whose hunting-patterns

I knew nothing of. I found one building, the only two-story one, that not only had a door but also still had

a bit of roof on it, and hunkered down in the driest corner I could find. I took off my clothes and shook

as much water from them as I could, badly missing modern tough and water-repellant fabrics, dressed

again, though the warmth they gave was largely imaginary, then curled myself into a ball in an effort to

keep as much of that warmth as possible, and waited for the night and storm to pass. If the flash floods

came quickly they should fall equally quickly. I was still worried that the tigripard was tracking me, but

could see no sign of it.

In fact I fell asleep almost at once, without meaning to, but when I awoke nothing had changed.

Certainly it was now full dark night even without the piled-up storm-clouds. But getting to sleep a second

time was impossible.

One good thing had happened—like all UNSN troops I have had my night-vision enhanced by

nanosurgery and now my eyes had grown accustomed to the dark. It wasn't perfect but I made the most

of what light there was and in all but the darkest patches of night I was no longer completely blind and

helpless.

I've had my skin toughened a bit too, but despite that it was still very cold and miserably uncomfortable.

The sites of the injuries I had had in the battle with the mad ones in the caves a few months before were

aching in concert with the pain in my ankle despite all the miracles of modern medicine, and something, I

didn't then know what, was making me both more anxious and unhappy than I should have been.

I got up and set out to explore a little. Black as the night was, the almost continual lightning showed me

the empty rooms, long ago stripped of furnishings, miniature waterfalls from the gaps in the remnants of

roof and ceiling, and a broken staircase leading down into a cellar or shelter which I had no inclination to

enter. I could hear water down there splashing into mud, and I had no desire to get involved with more

mud or what might live there. In other rooms some small creatures that I could not make out clearly

scuttled away as I entered. I remembered the poison-fanged Beam's Beasts and gave them as wide a

berth as they gave me. As I expected, I found nothing useful. The house had been thoroughly stripped

long before.

Was that a light I could see out the window? The hail slackened for a while. With that bit of clearing I

could see further, and suddenly my spirits rose again. For there was, I saw between the lightning flashes,

indeed a dim orange square of light some way off.

The tigripard must be far away. Surely if it was nearby I would know by now. Perhaps it recognized the

.22 as a weapon. Perhaps like so many larger wild creatures it avoided even the ruins of Man. I didn't

know then that it had another good reason for keeping away from the house.

I wrenched down a splintered door lintel. A piece of it made a better crutch than my empty gun. Leaning

heavily on it, I set off up what had been that hamlet's only street. A black silhouette grew around that

orange square as I drew nearer: a bigger house standing by itself on a rise of ground. The light was an

upper window.

There was a path leading to the door, but as I approached it more closely I realized things: the house

was too big, the upper windows too high and small, while the ground-floor windows, where they

occurred at all, were mere slits, and dark. The door was too high and wide. And, as I said, the light in

that window was orange. There were other things about the architecture. This was not a human house but

a kzin one. I looked back and saw how on its rise of ground it dominated the hamlet and gave a view of

all the surrounding lands. This had been the mansion of the local kzin overseer of human slaves.

Plainly it had been slighted during the Liberation. I could make out, now that I looked, where the high

walls and towers that must have surrounded it in the old kzin architectural style would have stood. Their

rubble filled what must once have been a moat or ditch. I saw stumps of concrete and metal where

defense and security installations must have been torn down. Behind the house were some large storage

tanks, though I could not see whether or not they were intact. On the roof silhouetted against the sky in

the lightning there was no sign of the dishes or antennas of modern communications equipment.

But that light burning now was ruddy orange. Not white or yellow. Only kzinti liked that orange light.

Were there kzinti here still? It was quite possible. I knew that some of them still lived in the depopulated

districts, shunning humans for obvious reasons, and this place, purpose-built and to their size, still

relatively defensible, would be far more suitable for them than any others around. As I stood looking up

at it I saw the silhouette of someone or something cross the lighted window.

Well, I would ask no shelter or favors from kzinti. Both pride and prudence said that. I was a soldier

and I could stand an uncomfortable night in the ruins if necessary.

Trying to distance myself from the pain in my ankle, I hobbled back through the mud to the

ghost-hamlet. For no particular reason I knew, save that it seemed the best-roofed and I had left the .22

there, I returned to the first house I had entered and curled up in my former place.

Then the zeitungers came.

I didn't know then that's what it was. I had heard of the zeitungers, originally called the

zeitung-schreibers, of course, but I had never encountered them. And what I had heard of them had

given me no true idea of them or of what encountering a pack of them when alone at night and physically

spent was like.

Humans and kzinti alike on Wunderland loathed them and would stop at nothing to exterminate them.

Like the Advokats and the Beam's Beasts, however, they liked the ample food which they associated

with human activity. No one had told me they were often to be found in the ruins of human buildings here,

presumably because nobody thought I would be spending a night in such ruins. They were carrion-eating

vermin like the disgusting Advokats but with, in addition, an ability to project psychic damage and

distress which they used as a weapon, an especially potent one when they were packing. They didn't limit

themselves to carrion. The zeitungers' mental emanations could make a small-brained animal—an Earth

rabbit or dog, say—lie down and scream, waiting for them to mob it and tear it to pieces alive.

On a big-brained animal and especially on a sophont the effect was more complex. Cognitive

dissonance, a combination of pathological anxiety, hallucination, hypertension and, above and beneath

and overarching all, black, disabling, even killing, clinical depression—if "depression" is an adequate

word. Wunderland creatures had evolved a certain resistance to the zeitunger power. Earth animals, and

humans, had not. The creatures could apparently do nothing else mentally. They might be able to

communicate among themselves—every member of a shoal of fish or flock of birds on Earth can turn in

the same direction in an instant—but they were not telepaths. The only power their dim minds had was

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

Man-KzinWarsXITableofContentsTHREEATTABLEGROSSGEISTERSWAMPCATSPAWSChapter1Chapter2Chapter3Chapter4Chapter5Chapter6Chapter7Chapter8Chapter9Chapter10Chapter11Chapter12Chapter13Chapter14Chapter15TEACHER'SPETIIIIIIWARANDPEACETHEHUNTINGPARKMAN-KZINWARSXIHALCOLEBATCHANDMATTHEWHARRINGTONCREATEDBYLARRYNIVEN...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:230 页

大小:684.53KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-23

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394