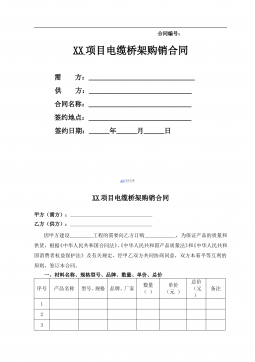

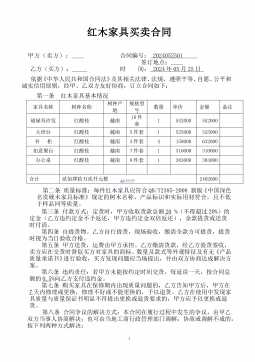

Steve White - Demons Gate

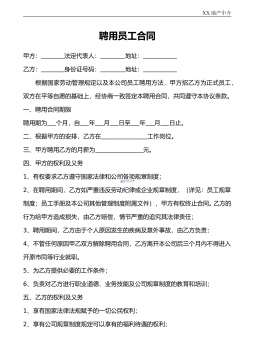

VIP免费

2024-12-20

3

0

584.95KB

187 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

Demon's Gate

Steve White

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this

book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or incidents is

purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2004 by Steve White

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions

thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

www.baen.com

ISBN: 0-7434-7176-8

Cover art by Clyde Caldwell

First printing, January 2004

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

White, Steve, 1946-

Demon's gate / Steve White.

p. cm.

"A Baen Books original."

ISBN 0-7434-7176-8 (Hardcover)

1. Demonology--Fiction. I. Title.

PS3573.H474777D46 2004

813'.54--dc22

2003020724

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Production by Windhaven Press, Auburn, NH

Printed in the United States of America

To Sandy, for the love which is the

most precious thing I possess.

And to Richard A. Getchell, for allowing

Irma Sanchez the use of a great line.

BAEN BOOKS by STEVE WHITE

Demon's Gate

Forge of the Titans

Eagle Against the Stars

Prince of Sunset

Emperor of Dawn

The Disinherited

Legacy

Debt of Ages

with David Weber:

Insurrection

Crusade

In Death Ground

The Shiva Option

Author's Note

At the risk of belaboring the obvious, Demon's Gate is a fantasy. Its setting is not our

own world's Bronze Age, although its geography and climatology are markedly similar. It

mirrors European prehistory, but with larger and more developed political units and a

higher level of sophistication about certain things, most notably theology. (As far as the

latter is concerned, a case can be made for the presence of Zoroastrian-style dualism a

thousand years early. After all, in the Demon's Gate world it's real . . . more or less, as

Nyrthim would say.) At the same time, the mundane technology of this world—

metallurgy, shipbuilding, construction techniques, chariots and their use, and so forth—is

as accurate in terms of our current knowledge of the European Bronze Age as

conscientious research can make it.

The pronunciation of the various languages is fairly self-explanatory. Final vowels

are always sounded. The aa combination in Dovnaan words represents an ah sound

shading toward aw. In words of Nimosei derivation (including numerous names and loan-

words in Ayoliysei, such as "Ayoliysei" itself), iy approximates a shortened one-syllable

form of the sound sometimes rendered as aiee.

I make no apologies for using English units of measurement. Metrics would be even

more anachronistic. More anachronistic still would be to put fashionable modern

sentiments on such subjects as slavery, war, social equality and gender roles into the

mouths of the characters.

PART ONE:

The City

CHAPTER ONE

The mist through which they sailed was unusual for the Inner Sea.

"Nothing to compare to what we're used to, of course," stated Khaavorn.

Valdar smiled. His companion had yet to admit that anything in these regions could

compare with home. In this case, though, he had a point. The island of Lokhrein from

which they'd departed a moon and a half ago was almost fogbound enough to justify its

reputation. Here, the sun kept breaking through rifts to awaken eye-dazzling sparkles on

the water. Still, this mist was enough to veil the northern coast of Schaerisa to starboard,

and the galley seemed to glide through a pearl-white world of blended air and sea with no

land at all.

But then, abruptly, they were out of the pocket of mist and back in the sunlight whose

brilliance and clarity almost hurt their northern eyes, under the sky whose blueness

Valdar had never gotten used to. Off to starboard was the coast of Schaerisa with its little

whitewashed fishing villages. Ahead rose one of the rocky ridges that broke up this

island's coast into a series of crescent-shaped coves, forming a headland.

As they drew abreast that headland, a cleft in the ridge gave them a glimpse of what

lay beyond . . . and for once, Khaavorn was silent.

They'd heard tales of The City, of course. Khaavorn had scoffed loudly, and in his

quieter way Valdar had agreed. But now, as the galley moved on and the cleft fell behind,

the two of them turned to each other and exchanged a nervous glance, both wondering if

they'd really seen what they thought they'd seen but neither willing to be the first to voice

the question. Unconsciously, Khaavorn's hand went to the smooth-worn haft of the heavy

war axe that was the weapon, emblem and soul of a Dovnaan warrior. Valdar smiled

condescendingly . . . but then realized that his own hand had sought the hilt of his sword.

Then they rounded the headland. Ahead was another rocky prominence, not unlike it.

At a bawled command from the captain, the steersmen hauled on the twin rudders and the

galley heeled to starboard, turning into the channel between the two capes. Khaavorn and

Valdar held onto the rail to keep their footing . . . and stared ahead at the vista for which

no traveler's tale had prepared them.

The two curving headlands enclosed a vast harbor, universally conceded to be the

finest in the world, rimmed by gentle hills where villas peered forth from groves of olive

trees and date palms. Arguably it was two harbors, for it was divided almost precisely in

half by a peninsula extending from the harbor's southern shore. The head of that

peninsula now lay dead ahead, like a mountain rising from the water . . . not a natural

mountain made by the gods, but an artificial mountain fashioned by men like gods, for

this was The City.

That was all anyone ever called it. Its actual name was Schaerisa, the same as the

island. But it needed no name on any of the coasts and islands of the Inner and Outer

Seas that the Old Empire had once ruled. It was simply The City.

It rose in tiers and terraces of stone and masonry and ruddy-tiled roofs, climbing the

slopes of two hills. One of those hills was crowned with the temple of Dayu, gleaming

with decorative tiles and gold leaf. The other seemed to groan beneath the weight of the

imperial palace, whose colonnaded and porticoed façade was like nothing the two of

them—the son of one king and the nephew of another—had ever seen, or imagined.

And yet those two hills were only foothills of a conical mountain whose jagged

cinder-gray peak loomed above all the clutter of buildings.

A volcano, Valdar found himself wondering, that once blasted its lava out and left the

crater that is now a harbor? That's the kind of thing Nyrthim would have wondered about.

He shied away from the thought, as he always did whenever such strange speculations

entered his mind, which they they doubtless did at the behest of the old sorcerer's ghost.

The harbor was alive with ships—lean predatory war galleys and the broad-beamed

merchantmen that were their natural prey, tied up at the docks as well as under way. A

small but well-kept-up boat approached in a way that somehow exuded arrogance. In its

stern stood a middle-aged man who, under his official dress of white kilt and formal over-

both-shoulders mantle, suggested gauntness settling into softness. He bore a staff of

office.

"What is your business here?" he demanded when his craft had drawn into shouting

range. He used the Nimosei that was still the common language of commerce in the lands

once ruled by the Old Empire.

"The harbormaster," grunted the captain. He was from the land the imperials still

officially called Ivaerisa, where Khaavorn and Valdar had negotiated passage the rest of

the way through the Inner Sea, and he had the strongly built hook-nosed look that went

with that land's Escquahar blood. Unfortunately, a legacy of suspicion also went with it,

here in the New Empire. "This is the Wave Leaper, out of Ivaerisa," he called out, leaning

over the rail, "bringing distinguished visitors."

"We are uninterested in any louse-infested rebel or barbarian dignitaries you may

have brought from Ivaerisa," the harbormaster sneered, using the first person plural in the

way of all officials in all times and places. "And the investiture was weeks ago—as I

should have thought everyone knew by now. Proceed to the commercial docks, along

with the rest of the outlanders and the lower orders."

Khaavorn flushed. This was just the thing to bring him out of his paralyzing awe. He

pushed the captain aside and glared across the water, axe held so as to be just visible over

the gunwale. His Nimosei had been learned in childhood—his family, like many of

Lokhrein's ruling clans, blended the bloodlines of the Old Empire's priesthood with those

of the conquering Dovnaan. But now he spoke in the Ayoliysei dialect that was the New

Empire's ruling language. He and Valdar had acquired it without undue difficulty, for it

and the Dovnaan tongue had common roots going back not so very many generations.

But Khaavorn's Dovnaan accent was now even thicker than usual—thicker, Valdar

suspected, than it needed to be.

"This young gentleman," he declared, waving grandly at Valdar, "is heir to King

Arkhuar of Dhulon. An' I meself am Khaavorn nak'Moreg, sister's son to Riodheg, High

King of Lokhrein. I've also the honor of bein' half brother to the Lady Andonre, wife of

Vaelsaru, chief general of your Emperor . . . who, ye may be sure, will be hearin' of any

insolence we encounter from his servants!"

The harbormaster managed to grovel without capsizing his boat. "My humblest and

most abject apologies, lord! I naturally never dreamed that this, uh, vessel carried

passengers of such eminence. Please permit me to escort you to the imperial moorings."

He gestured peremptorily at his steersman, who bawled at the oarsmen, thus confirming

the immemorial proverb of the ancient sage Zhaerosa: "Shit flows downhill."

Khaavorn turned to Valdar and smoothed his mustache complacently. "One just has

to know how to deal with those sorts of people, that's all," he explained in their more

usual Dovnaan tongue.

"No doubt. But was that 'young gentleman' business really necessary? You make me

sound like I'm still the callow little twit who arrived in Lokhrein ten years ago begging

help from the High King for his old ally Arkhuar."

"And so you are!" boomed Khaavorn. He flung an arm around the younger man's

shoulders. "You may have fooled some people into thinking you're a proper warrior of

the Dovnaan, foreigner though you are. But I, for my manifold offenses against Dayu,

was your mentor. So I know better!"

Valdar grinned, unabashed. "Yes. How well I remember the style of your instruction!

It's no exaggeration to say you made me what I am today."

Khaavorn winced. "Now that was low!"

He was, Valdar reflected, remarkably little changed from those days, though now in

his mid-thirties: tall, powerfully built, with the wide shoulders and heavily developed

muscles that came from wielding the heavy war axe from early adolescence. His strong

features were likewise of the sort Dovnaan warrior aristocrats were popularly supposed to

have—hawklike nose, high cheekbones, heavy jaw—and he wore his hair in their style,

long and gathered into a ponytail, with a drooping mustache but otherwise as clean-

shaven as bronze razors permitted. But that hair was of a very dark brown, with only a

slight coppery undertone, and his eyes were just as dark, a legacy of Lokhrein's older

rulers.

Valdar was even darker-haired, and his slender build and straight features were those

of the people who had spread the religion of Rhaeie the Mother—and with it the writ of

the Old Empire—from the Inner Sea all the way to the cold northern land that was later to

be named Dhulon by the Karsha conquerors who'd bequeathed Valdar his tallness and his

blue-gray eyes. He wore the same kind of Dovnaan garb as Khaavorn: knee-length

woolen tunic, broad belt with studs and buckle of copper, short mantle caught at the left

shoulder by a massive gold brooch, the basic color deep blue in his case and forest green

in Khaavorn's, edged with elaborate embroidery. But he asserted his heritage by wearing

his hair shorter and shaving his mustache as well as his beard.

Neither of them had armor or helmets—this was a peaceful visit—although even

without all that bronze they were sweating in the southern spring. But they bore the

weapons without which they would have felt naked: Khaavorn's war axe and Valdar's

sword.

"They say no one is allowed into the Emperor's presence with weapons," said Valdar,

changing the subject.

Khaavorn expressed his opinion with a snort. He automatically lifted his war axe by

its haft of fire-hardened wood. The head was a thing of sinister beauty, the product of a

tradition that had worked the same shape in polished stone in the days before bronze. The

thick blade curved backward in flowing lines to swell into a spiked ball through which

the haft was inserted. Behind, the lines continued downward, forming a wicked hook. It

was a weapon of terrifying potentialities in the hands of a large, strong wielder—the only

kind who could wield it effectively.

"Ridiculous notion! They can't possibly expect a gentleman to go unarmed—even if

he's only armed with that."

Valdar smiled easily at the familiar gibe. "You're hopelessly old-fashioned," he said,

patting the hilt of his sword. Perfectly balanced, its two-and-a-half-foot blade was a

slender leaf-shape designed for cutting and thrusting. It was an import from Khrunetore,

whose weapon-smiths had developed a technique of coating bronze with chromium,

enabling it to hold an edge keen enough to cut a hair. Some people whispered of demonic

assistance. Khaavorn wasn't one of those. He'd merely fulminated loudly about

newfangled tomfool foreign innovations . . . and, with no noise at all, learned to use a

sword himself.

"Speaking of the imperial presence," said Valdar, shifting subjects again (partly

because he knew it annoyed Khaavorn), "the harbormaster's dig about the investiture

being over reminded me that there's now just one of them."

"Oh, yes." They'd heard the news of old Namapa's death at the newly reconquered

imperial island of Sardiysa, where the ship had put in a week earlier. "Naturally I didn't

give him the satisfaction of admitting we'd hoped to be in time for it! Hmmm . . . So now

Tarhynda is officially the sole Emperor. Well, we can still pay the High King's respects to

him." Khaavorn grew subdued. "Some of the stories we've heard . . ."

"I'll keep an open mind for now."

"Of course. And it will be good to see my half sister again. Little Andonre . . ." But

Khaavorn's jovial mood was gone. He gazed stonily across the water, and Valdar

followed his gaze.

The peninsula ahead was largest at its hilly tip around the volcanic cone where The

City rose, so it was more like an island filling much of the center of the great lagoonlike

harbor, connected to the south shore by a narrow isthmus. Valdar had heard that a

massive wall cinctured that isthmus, though it wasn't visible from here. The Ayoliysei

dynasts of the New Empire weren't likely to repeat the mistake of the Old, whose cities

had been undefended save by their fleets. But only low sea walls faced the harbor, as

became clear as they drew closer.

It also became clear that the harbormaster was exacting a functionary's petty revenge,

for his boat was leading them to the naval docks, not to the private ones at the foot of the

palace hill—those were, it seemed, too good for semi-barbarian lordlings from former

imperial provinces, however well-connected. The quay to which they tied up was closer

to the lesser hill on which the temple of Dayu rose in its gilded splendor. Nearby, at the

foot of that hill and extending over the water on pillars, was a small shrine to Rhaeie the

Mother, in her aspect of Mistress of the Waves.

As they disembarked, they made the appropriate signs of thanks for a safe voyage in

the direction of the Mother's shrine. But Khaavorn could not conceal a frown at the

temple's ostentatiously subordinate position. It was not his full-blown scowl, however. It

was more a look of perplexity. He worshipped Dayu, of course. All Dovnaan warriors

did—they even called him by the same name, and the priests were in surprising

agreement that the Lord of Light and Good was the same in every land where the Karsha

tribes had brought his worship. However, the ancient traditions ran strongly in his family.

Valdar understood his companion's ambivalence, for he shared it.

The captain approached after hurried consultation with a bronze-helmeted officer.

"I've arranged for you to be allowed to depart at once." He indicated a gateway in the sea

wall, with broad shallow steps leading up to street level. There a crowd had already

gathered, shrilly advertising themselves as guides . . . or for other services. "I know a

guide who's almost honest. He'll conduct you to the palace, or wherever else you wish to

go. Or if you would prefer for me to order litters . . . ?"

"No, just the guide," said Khaavorn with distaste. "We'll walk." He motioned to his

servant to collect his belongings. Valdar did the same . . . except that Wothorg wasn't

really a servant.

"Come on, Wothorg," he called. "Your pleasure cruise is over."

"Good name for it, in the pond water these southerners call seas," came a bass rumble

from beyond the rail, followed by Wothorg, walking without apparent effort under the

load he was carrying. He was a descendant of the original folk of Dhulon who'd stared

awestruck at the ships that had heralded the Old Empire so long ago. Not as tall as

Valdar, he was approximately twice as broad and twice as thick—at least if one counted

his paunch, under which lay rock-hardness. His eyes, blue as northern ice, looked out

from under shaggy yellow brows. Those eyes seemed squeezed into slits by his rubicund

jowls—which, in turn, were barely visible above his dense reddish-blond beard.

When Arkhuar had sent his son—because there was no one else—to seek the help of

the High King of Lokhrein, he'd also sent a trusted retainer to guard the boy's back.

Afterwards, when Valdar had remained in Lokhrein in Riodheg's service—with the

blessings of his father, who thought it the best possible preparation for Dhulon's future

king—Wothorg had remained as well. And he was still along now, under the southern

sun that caused his blunt red nose to peel continuously.

Not that I need a bodyguard this time, Valdar told himself. This is just a courtesy call

on Tarhynda, now that he's become sole Emperor, to deliver the best wishes of the High

King whose existence the Empire has never officially recognized, and to renew the trade

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

Demon'sGateSteveWhiteThisisaworkoffiction.Allthecharactersandeventsportrayedinth\isbookarefictional,andanyresemblancetorealpeopleorincidentsispurelycoincidental.Copyright©2004bySteveWhiteAllrightsreserved,includingtherighttoreproducethisbookorporti\onsthereofinanyform.ABaenBooksOriginalBaenPublishin...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:187 页

大小:584.95KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-20

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394