Robinson, Spider - By Any Other Name

VIP免费

2024-12-20

3

0

1.07MB

170 页

5.9玖币

侵权投诉

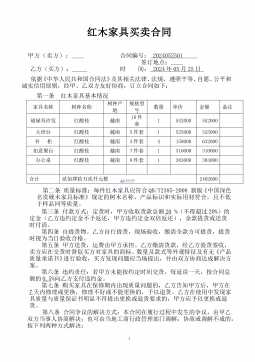

By Any Other Name

Spider Robinson

Fout! Onbekende schakeloptie-instructie.

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this book are fictional, and any resemblance to real people or

incidents is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2001 by Spider Robinson

All stories copyright by Spider Robinson: Melancholy Elephants © 1984, Half An Oaf © 1976, Antinomy © 1980, Satan’s Children © 1979, Apogee © 1980, No

Renewal © 1980, Tin Ear ©, 1980, In the Olden Days © 1984, Silly W e a p o n s © 1 9 8 0 , Nobody Likes to Be Lonely © 1 9 8 0 , “If This Goes On—” © 1991, True Minds ©

1984, Common Sense © 1985, Chronic Offender © 1984, High Infidelity © 1984, Rubber Soul © 1984, The Crazy Years was originally published in parts in the

Toronto Globe and Mail © 1996–2000, By Any Other Name © 1976.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

A Baen Books Original

Baen Publishing Enterprises

P.O. Box 1403

Riverdale, NY 10471

www.baen.com

ISBN: 0-671-31974-4

Cover art by Richard Martin

Interior art by Rocky Coffin

First printing, February 2001

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Production by Windhaven Press, Auburn, NH

Printed in the United States of America

For my friends Ted and Diana Powell

—and for Ben Bova,

without whom all this would not have been necessary . . .

BAEN BOOKS by Spider Robinson

By Any Other Name

The Star Dancers (with Jeanne Robinson)

Starmind (with Jeanne Robinson) (forthcoming)

Deathkiller

Lifehouse

User Friendly

Telempath (forthcoming)

FOREWORD

Perhaps a story collection should be allowed to speak for itself.

That was my original intention; I submitted this book to Toni Weisskopf without a foreword. The basic plan was

simple: to gather all the short stories I’ve written that aren’t already collected in User Friendly (Baen 1998), with a little

bit of nonfiction for lagniappe. So the assembly process was not onerous. Basically I pulled manuscripts from the trunk,

glanced at their titles, nodded nostalgically, and added them to the pile. Deciding their order was a no-brainer: begin

and end with a Hugo-winner, and in between those, alternate humorous and serious stories. Writing a foreword

seemed superfluous.

Then a few days ago the galley proofs arrived, and I sat down and read them through, and here I am writing a

foreword after all.

I have not written short fiction for some time now. Novels pay so much better that, without consciously planning

to, I just stopped getting short story ideas a few years back. So I hadn’t read any of those stories particularly recently.

Some I had not read in twenty years or more. As I rediscovered them now, unexpected patterns emerged.

I’d begun the galleys firmly resolved to do nothing but correct typos. I was determined to make no retroactive

improvements to these stories—to let them stand as they first came into the world, flaws and all. But I found I kept

wanting to push dates forward. I was rather startled to realize how many of these stories are now chronologically

outdated. Written, in some cases, in the early 1970s, they tended to be set in the “distant future” of twenty or thirty

years later. I’m most comfortable in that range: the further ahead into the future I speculate, the less confident I am

about my own guesses—and if I’m dubious, how am I to convince a reader? But history has begun to overtake me.

I was not dismayed—or even surprised—at how often my guesses about the future had turned out to be dead

wrong. I’ve never claimed or wished to be a prophet; I write about possible futures, and strive for plausible ones.

But I was somewhat surprised at just how my speculations were wrong: over and over, it seems, I was too

optimistic. I don’t mean that all the stories you’re about to read are upbeat, by any means. But most of the futures I

imagined were, in retrospect, at least a little better than the one we actually got. At least more technologically

advanced.

I find I’m proud of that.

I only pray I can manage to sustain that attitude of positive expectation, that tendency toward benign delusion,

through the next quarter-century of tumult and shenanigans. And infect as many other people with it as possible.

Because unconscious expectations are so important. We need all the Placebo we can get. It’s been shown again

and again: if you introduce a new teacher to a perfectly average class of kids, and tell him they’re the Advanced

group, by the end of the year they will be. This real year 2000 may not be quite as advanced as some of the ones I

envisioned for entertainment purposes . . . but it is, I think, a far nicer one than most average citizens living in the

1970s or 1980s would have believed possible. (Just for a start: no Cold War.) Optimistic science fiction may just

have had something to do with that. As my friend Stephen Gaskin once said, “What you put your attention on

prospers.”

Case in point: the title story of this book.

It was, if memory serves, the third story I ever tried to write for money. I’d sent my first one to the most popular

magazine in the field, Analog—talk about irrational optimism—and miraculously, it sold. But the second, set in the

same tavern, had not sold there . . . or anywhere else. Then from somewhere came “By Any Other Name,” and I just

knew this one was going to sell. Perhaps it’s weird to call it an optimistic story, since it posits the total collapse of

technological civilization—but it also suggests that humanity will ultimately survive just about any collapse. In any

event, it was a much more complex and ambitious story than anything I’d ever tried before, and I certainly sent it off

with high hopes.

It was bounced by every market in science fiction.

More than a dozen rejections, beginning with Analog and ending underneath the bottom of the barrel. The last

editor on the list lost the damn thing for several months . . . then rejected it . . . then lost it again. (I was so green, the

only other copy in existence was the handwritten first draft.)

By the time I finally got it back, I had written several other stories, and not one of them had sold, either. I suspect

the only reason I even took the manuscript out of the envelope was so it would burn better in the fireplace. But my

own opening sentence caught me. I ended up reading the damn thing all the way through one more time—

—and by God, I still liked it. All thirteen of those editors, I decided on the spot, were wrong.

So I rejected the rejections. I mailed the story, unchanged, to Ben Bova at Analog a second time. It was a perfect

act of irrational optimism, of benign delusion.

You guessed it: he bought it this time.

But it wasn’t just a sale. “By Any Other Name” was my first Analog cover story. (Jack Gaughan’s splendid

painting for that cover hangs in my home today; God rest his generous soul.) It won my first AnLab, the monthly

Analog reader’s poll. A year later it won me my first Hugo Award from readers worldwide. It was a career-maker. It

became the nucleus of my first novel, Telempath. Most important of all, it was one of a pair of stories which

persuaded a young woman named Jeanne, in spite of her better judgment, to let me court her . . .

So maybe that’s one reason why I’m optimistic by policy. It seems to be working for me.

(Epilogue I can’t resist: over a decade later, I got up the nerve to ask Ben if he realized he’d rejected a Hugo-

winning story the first time he saw it. Oh sure, he said, I had to—no choice. How come? I asked.

(He gave me a pitying look. “Spider, that was an election year—remember? And then you expect me to buy a

story where the alien villains are basically giant killer farts, named ‘Musky’?” He shook his head emphatically.

“Nixon that.”)

In that spirit of reckless optimism, I’ve adulterated this collection of short fiction with a pinch of non-fiction.

One evening in 1996 Jeanne and I were strolling through town with our friend Shannon Rupp, then the dance

critic for Vancouver’s alternative weekly The Georgia Straight, and as is my custom, I was shooting my mouth off.

An airliner had just fallen into the sea, and all the media believed it had either been terrorist sabotage, or just possibly

a covered-up accidental missile launch from a U.S. Navy destroyer. I was pontificating on why both theories had to

be hogwash . . . and Shannon interrupted. “Write that all down,” she said. And do what with it, I asked. “Send it to

The Globe and Mail,” she said. “I’ll bet they buy it.”

Well, that was just silly. The Globe and Mail was Canada’s national newspaper, its journal of record, the Grey

Lady of the North. What would they want with the unsolicited opinions of an American-born science fiction writer

who lived about as far from Toronto as a Canadian resident can get, and whose most recent journalistic credentials—

lame ones—were almost thirty years old?

But Shannon finally bullied me into trying it. And Warren Clements bought the piece, and asked for more, and

that’s how I became an Op-Ed columnist—like nearly everything else I’ve accomplished in my life so far: by

accident.

I’ve provided herein some samples of the column that ran in The Globe and Mail every three weeks from 1996–

99 under the running title, “The Crazy Years.” If you don’t care for fact—or at least, for opinions about facts—with

your fiction, by all means skip over them. If they do catch your interest, as of this writing I’m still producing a

column a month for The Globe and Mail, and two columns a month for David Gerrold and Ben Bova’s new cybersite

Galaxy Online (www.galaxyonline.com).

And now on to the fiction. After all this talk of optimism, naturally the first story in line, which won the 1983

Hugo for Short Story, is one of the gloomier prognostications I’ve ever made. Oh well. The year “Melancholy

Elephants” is set in has not arrived yet—maybe this time the real future will turn out brighter than the one I dreamed.

One can hope . . .

—British Columbia

18 September, 2000

Melancholy

Elephants

This story is dedicated to

Virginia Heinlein

She sat zazen, concentrating on not concentrating, until it was time to prepare for the appointment. Sitting seemed

to produce the usual serenity, put everything in perspective. Her hand did not tremble as she applied her make-up;

tranquil features looked back at her from the mirror. She was mildly surprised, in fact, at just how calm she was, until

she got out of the hotel elevator at the garage level and the mugger made his play. She killed him instead of disabling

him. Which was obviously not a measured, balanced action—the official fuss and paperwork could make her late.

Annoyed at herself, she stuffed the corpse under a shiny new Westinghouse roadable whose owner she knew to be in

Luna, and continued on to her own car. This would have to be squared later, and it would cost. No help for it—she

fought to regain at least the semblance of tranquility as her car emerged from the garage and turned north.

Nothing must interfere with this meeting, or with her role in it.

Dozens of man-years and God knows how many dollars, she thought, funnelling down to perhaps a half hour of

conversation. All the effort, all the hope. Insignificant on the scale of the Great Wheel, of course . . . but when you

balance it all on a half hour of talk, it’s like balancing a stereo cartridge on a needlepoint: It only takes a gram or so

of weight to wear out a piece of diamond. I must be harder than diamond.

Rather than clear a window and watch Washington, D.C. roll by beneath her car, she turned on the television. She

absorbed and integrated the news, on the chance that there might be some late-breaking item she could turn to her

advantage in the conversation to come; none developed. Shortly the car addressed her: “Grounding, ma’am. I.D.

eyeball request.” When the car landed she cleared and then opened her window, presented her pass and I.D. to a

Marine in dress blues, and was cleared at once. At the Marine’s direction she re-opaqued the window and

surrendered control of her car to the house computer, and when the car parked itself and powered down she got out

without haste. A man she knew was waiting to meet her, smiling.

“Dorothy, it’s good to see you again.”

“Hello, Phillip. Good of you to meet me.”

“You look lovely this evening.”

“You’re too kind.”

She did not chafe at the meaningless pleasantries. She needed Phil’s support, or she might. But she did reflect on

how many, many sentences have been worn smooth with use, rendered meaningless by centuries of repetition. It was

by no means a new thought.

“If you’ll come with me, he’ll see you at once.”

“Thank you, Phillip.” She wanted to ask what the old man’s mood was, but knew it would put Phil in an

impossible position.

“I rather think your luck is good; the old man seems to be in excellent spirits tonight.”

She smiled her thanks, and decided that if and when Phil got around to making his pass she would accept him.

The corridors through which he led her then were broad and high and long; the building dated back to a time of

cheap power. Even in Washington, few others would have dared to live in such an energy-wasteful environment. The

extremely spare decor reinforced the impression created by the place’s dimensions: bare space from carpet to ceiling,

broken approximately every forty meters by some exquisitely simple object d’art of at least a megabuck’s value,

appropriately displayed. An unadorned, perfect, white porcelain bowl, over a thousand years old, on a rough

cherrywood pedestal. An arresting color photograph of a snow-covered country road, silk-screened onto stretched

silver foil; the time of day changed as one walked past it. A crystal globe, a meter in diameter, within which danced a

hologram of the immortal Shara Drummond; since she had ceased performing before the advent of holo technology,

this had to be an expensive computer reconstruction. A small sealed glassite chamber containing the first vacuum--

sculpture ever made, Nakagawa’s legendary Starstone. A visitor in no hurry could study an object at leisure, then

walk quite a distance in undistracted contemplation before encountering another. A visitor in a hurry, like Dorothy,

would not quite encounter peripherally astonishing stimuli often enough to get the trick of filtering them out. Each

tugged at her attention, intruded on her thoughts; they were distracting both intrinsically and as a reminder of the

measure of their owner’s wealth. To approach this man in his own home, whether at leisure or in haste, was to be

humbled. She knew the effect was intentional, and could not transcend it; this irritated her, which irritated her. She

struggled for detachment.

At the end of the seemingly endless corridors was an elevator. Phillip handed her into it, punched a floor button,

without giving her a chance to see which one, and stepped back into the doorway. “Good luck, Dorothy.”

“Thank you, Phillip. Any topics to be sure and avoid?”

“Well . . . don’t bring up hemorrhoids.”

“I didn’t know one could.”

He smiled. “Are we still on for lunch Thursday?”

“Unless you’d rather make it dinner.”

One eyebrow lifted. “And breakfast?”

She appeared to consider it. “Brunch,” she decided. He half-bowed and stepped back.

The elevator door closed and she forgot Phillip’s existence.

Sentient beings are innumerable; I vow to save them all. The deluding passions are limitless; I vow to extinguish

them all. The truth is limitless; I—

The elevator door opened again, truncating the Vow of the Bodhisattva. She had not felt the elevator stop—yet

she knew that she must have descended at least a hundred meters. She left the elevator.

The room was larger than she had expected; nonetheless the big powered chair dominated it easily. The chair also

seemed to dominate—at least visually—its occupant. A misleading impression, as he dominated all this massive

home, everything in it and, to a great degree, the country in which it stood. But he did not look like much.

A scent symphony was in progress, the cinnamon passage of Bulachevski’s “Childhood.” It happened to be one of

her personal favorites, and this encouraged her.

“Hello, Senator.”

“Hello, Mrs. Martin. Welcome to my home. Forgive me for not rising.”

“Of course. It was most gracious of you to receive me.”

“It is my pleasure and privilege. A man my age appreciates a chance to spend time with a woman as beautiful and

intelligent as yourself.”

“Senator, how soon do we start talking to each other?”

He raised that part of his face which had once held an eyebrow.

“We haven’t said anything yet that is true. You do not stand because you cannot. Your gracious reception cost me

three carefully hoarded favors and a good deal of folding cash. More than the going rate; you are seeing me

reluctantly. You have at least eight mistresses that I know of, each of whom makes me look like a dull matron. I

concealed a warm corpse on the way here because I dared not be late; my time is short and my business urgent. Can

we begin?”

She held her breath and prayed silently. Everything she had been able to learn about the Senator told her that this

was the correct way to approach him. But was it?

The mummy-like face fissured in a broad grin. “Right away. Mrs. Martin, I like you and that’s the truth. My time

is short, too. What do you want of me?”

“Don’t you know?”

“I can make an excellent guess. I hate guessing.”

“I am heavily and publicly committed to the defeat of S.4217896.”

“Yes, but for all I know you might have come here to sell out.”

“Oh.” She tried not to show her surprise. “What makes you think that possible?”

“Your organization is large and well-financed and fairly efficient, Mrs. Martin, and there’s something about it I

don’t understand.”

“What is that?”

“Your objective. Your arguments are weak and implausible, and whenever this is pointed out to one of you, you

simply keep on pushing. Many times I have seen people take a position without apparent logic to it—but I’ve always

been able to see the logic if I kept on looking hard enough. But as I see it, S.’896 would work to the clear and lasting

advantage of the group you claim to represent, the artists. There’s too much intelligence in your organization to

square with your goals. So I have to wonder what you are working for, and why. One possibility is that you’re

willing to roll over on this copyright thing in exchange for whatever it is that you really want. Follow me?”

“Senator, I am working on behalf of all artists—and in a broader sense—”

He looked pained, or rather, more pained. “. . . ‘for all mankind,’ oh my God, Mrs. Martin, really now.”

“I know you have heard that countless times, and probably said it as often.” He grinned evilly. “This is one of

those rare times when it happens to be true. I believe that if S.‘896 does pass, our species will suffer significant

trauma.”

He raised a skeletal hand, tugged at his lower lip. “Now that I have ascertained where you stand, I believe I can

save you a good deal of money. By concluding this audience, and seeing that the squeeze you paid for half an hour of

my time is refunded pro rata.”

Her heart sank, but she kept her voice even. “Without even hearing the hidden logic behind our arguments?”

“It would be pointless and cruel to make you go into your spiel, ma’am. You see, I cannot help you.”

She wanted to cry out, and savagely refused herself permission. Control, whispered a part of her mind, while

another part shouted that a man such as this did not lightly use the words, “I cannot.” But he had to be wrong.

Perhaps the sentence was only a bargaining gambit. . . .

No sign of the internal conflict showed; her voice was calm and measured. “Sir, I have not come here to lobby. I

simply wanted to inform you personally that our organization intends to make a no-strings campaign donation in the

amount of—”

“Mrs. Martin, please! Before you commit yourself, I repeat, I cannot help you. Regardless of the sum offered.”

“Sir, it is substantial.”

“I’m sure. Nonetheless it is insufficient.”

She knew she should not ask. “Senator, why?”

He frowned, a frightening sight.

“Look,” she said, the desperation almost showing through now, “keep the pro rata if it buys me an

answer! Until I’m convinced that my mission is utterly hopeless, I must not abandon it: answering me is the quickest way to

get me out of your office. Your scanners have watched me quite thoroughly, you know that I’m not abscamming

you.”

Still frowning, he nodded. “Very well. I cannot accept your campaign donation because I have already accepted

one from another source.”

Her very worst secret fear was realized. He had already taken money from the other side. The one thing any

politician must do, no matter how powerful, is stay bought. It was all over.

All her panic and tension vanished, to be replaced by a sadness so great and so pervasive that for a moment she

thought it might literally stop her heart.

Too late! Oh my darling, I was too late!

She realized bleakly that there were too many people in her life, too many responsibilities and entanglements. It

would be at least a month before she could honorably suicide.

“—you all right, Mrs. Martin?” the old man was saying, sharp concern in his voice.

She gathered discipline around her like a familiar cloak. “Yes, sir, thank you. Thank you for speaking plainly.”

She stood up and smoothed her skirt. “And for your—”

“Mrs. Martin.”

“—gracious hos—Yes?

“Will you tell me your arguments? Why shouldn’t I support ‘896?”

She blinked sharply. “You just said it would be pointless and cruel.”

“If I held out the slightest hope, yes, it would be. If you’d rather not waste your time, I will not compel you. But I

am curious.”

“Intellectual curiosity?”

He seemed to sit up a little straighter—surely an illusion, for a prosthetic spine is not motile. “Mrs. Martin, I

happen to be committed to a course of action. That does not mean I don’t care whether the action is good or bad.”

“Oh.” She thought for a moment. “If I convince you, you will not thank me.”

“I know. I saw the look on your face a moment ago, and . . . it reminded me of a night many years ago. Night my

mother died. If you’ve got a sadness that big, and I can take on a part of it, I should try. Sit down.”

She sat.

“Now tell me: what’s so damned awful about extending copyright to meet the realities of modern life?

Customarily I try to listen to both sides before accepting a campaign donation—but this seemed so open and shut, so

straightforward . . .”

“Senator, that bill is a short-term boon, to some artists—and a long-term disaster for all artists, on Earth and off.”

“ ‘In the long run, Mr. President,’ ” he began quoting Keynes.

“—we are some of us still alive,” she finished softly and pointedly. “Aren’t we? You’ve put your finger on part of

the problem.”

“What is this disaster you speak of?” he asked.

“The worst psychic trauma the race has yet suffered.”

He studied her carefully and frowned again. “Such a possibility is not even hinted at in your literature or

materials.”

“To do so would precipitate the trauma. At present only a handful of people know, even in my organization. I’m

telling you because you asked, and because I am certain that you are the only person recording this conversation. I’m

betting that you will wipe the tape.”

He blinked, and sucked at the memory of his teeth. “My, my,” he said mildly. “Let me get comfortable.” He had

the chair recline sharply and massage his lower limbs; she saw that he could still watch her by overhead mirror if he

chose. His eyes were closed. “All right, go ahead.”

She needed no time to chose her words. “Do you know how old art is, Senator?”

“As old as man, I suppose. In fact, it may be part of the definition.”

“Good answer,” she said. “Remember that. But for all present-day intents and purposes, you might as well say

that art is a little over 15,600 years old. That’s the age of the oldest surviving artwork, the cave paintings at Lascaux.

Doubtless the cave-painters sang, and danced, and even told stories—but these arts left no record more durable than

the memory of a man. Perhaps it was the story tellers who next learned how to preserve their art. Countless more

generations would pass before a workable method of musical notation was devised and standardized. Dancers only

learned in the last few centuries how to leave even the most rudimentary record of their art.

“The racial memory of our species has been getting longer since Lascaux. The biggest single improvement came

with the invention of writing: our memory-span went from a few generations to as many as the Bible has been

around. But it took a massive effort to sustain a memory that long: it was difficult to hand-copy manuscripts faster

than barbarians, plagues, or other natural disasters could destroy them. The obvious solution was the printing press:

to make and disseminate so many copies of a manuscript or art work that some would survive any catastrophe.

“But with the printing press a new idea was born. Art was suddenly mass-marketable, and there was money in it.

Writers decided that they should own the right to copy their work. The notion of copyright was waiting to be born.

“Then in the last hundred and fifty years came the largest quantum jumps in human racial memory. Recording

technologies. Visual: photography, film, video, Xerox, holo. Audio: low-fi, hi-fi, stereo, and digital. Then computers,

the ultimate in information storage. Each of these technologies generated new art forms, and new ways of preserving

the ancient art forms. And each required a reassessment of the idea of copyright.

“You know the system we have now, unchanged since the mid-twentieth-century. Copyright ceases to exist fifty

years after the death of the copyright holder. But the size of the human race has increased drastically since the

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

ByAnyOtherNameSpiderRobinsonFout!Onbekendeschakeloptie-instructie.Thisisaworkoffiction.Allthecharactersandeventsportrayedinthisbookarefictional,andanyresemblancetorealpeopleorincidentsispurelycoincidental.Copyright©2001bySpiderRobinsonAllstoriescopyrightbySpiderRobinson:MelancholyElephants©1984,Half...

声明:本站为文档C2C交易模式,即用户上传的文档直接被用户下载,本站只是中间服务平台,本站所有文档下载所得的收益归上传人(含作者)所有。玖贝云文库仅提供信息存储空间,仅对用户上传内容的表现方式做保护处理,对上载内容本身不做任何修改或编辑。若文档所含内容侵犯了您的版权或隐私,请立即通知玖贝云文库,我们立即给予删除!

分类:外语学习

价格:5.9玖币

属性:170 页

大小:1.07MB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-12-20

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394