Robert Silverberg - Men and Machines

ForWaltColeCopyrightQMCMLXVIHbyRobertSilverbergPublishedbyarrangementwithMeredithPressAllrightsreserved.LibraryofCongressCatalogNumber:68-28721AWARDBOOKSarepublishedbyUniversal-AwardHouse,Inc.,asubsidiaryofCor235EastForty-fifthStreetNewYork,N.Y.10017TANDEMBOOKSarepublishedbyUniversal-TandemPublishin...

相关推荐

-

公司日常考勤制度VIP免费

2024-11-29 7

2024-11-29 7 -

公司人事考勤制度VIP免费

2024-11-29 9

2024-11-29 9 -

公司规章制度汇编VIP免费

2024-11-29 10

2024-11-29 10 -

岗位绩效工资制度VIP免费

2024-11-29 10

2024-11-29 10 -

保密制度汇编VIP免费

2024-11-29 11

2024-11-29 11 -

《绩效管理制度》VIP免费

2024-11-29 12

2024-11-29 12 -

《施工企业安全生产评价标准》JGJ/T-77—2010VIP免费

2024-12-14 191

2024-12-14 191 -

《潮起:中国创新型企业的诞生》导读VIP免费

2024-12-14 59

2024-12-14 59 -

岗位面试题库合集-通用面试题库-世界五百强面试题目及应答评点(全套50题)VIP免费

2024-12-15 67

2024-12-15 67 -

(试行)建设项目工程总承包合同示范文本GF-2011-0216VIP免费

2025-01-13 134

2025-01-13 134

作者详情

相关内容

-

49_2019年离职面谈技巧大全

分类:人力资源/企业管理

时间:2025-08-23

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

-

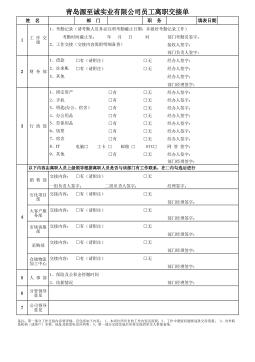

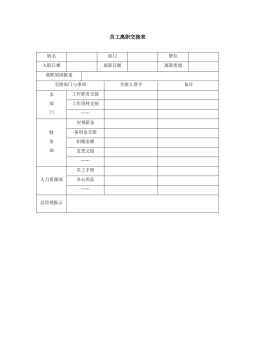

48_员工离职交接单

分类:人力资源/企业管理

时间:2025-08-23

标签:无

格式:XLS

价格:10 玖币

-

47_员工离职交接表-模板

分类:人力资源/企业管理

时间:2025-08-23

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

-

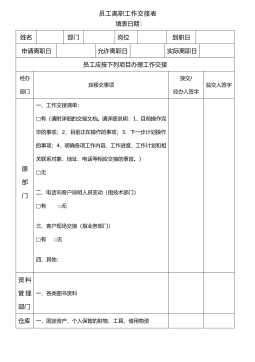

46_员工离职工作交接表

分类:人力资源/企业管理

时间:2025-08-23

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

-

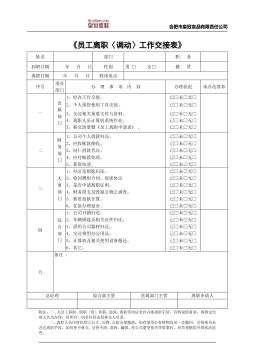

45_员工离职〈调动〉工作交接表

分类:人力资源/企业管理

时间:2025-08-23

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:10 玖币

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394