if there was anything he didn’t know about motor vehicles, it wasn’t very important. And through that medium he began to

get the general idea of what was going on.

Swarms of little men who might have been twins of the one he had spoken to were crowding around the cars, the

sidewalks, the stores and buildings. All were working like mad with every tool imaginable. Some were touching up the finish

of the cars with fine wire brushes, laying on networks of microscopic cracks and scratches. Some, with ball peens and mallets,

were denting fenders skillfully, bending bumpers in an artful crash pattern, spider-webbing safety-glass windshields. Others

were aging top dressing with high-pressure, needlepoint sandblasters. Still others were pumping dust into upholstery,

sandpapering the dashboard finish around light switches, throttles, chokes, to give a finger-worn appearance. Harry stood

aside as a half dozen of the workers scampered down the street bearing a fender which they riveted to a 1930 coupé. It was

freshly bloodstained.

Once awakened to this highly unusual activity, Harry stopped, slightly open-mouthed, to watch what else was going on.

He saw the same process being industriously accomplished with the houses and stores. Dirt was being laid on plate-glass

windows over a coat of clear sizing. Woodwork was being cleverly scored and the paint peeled to make it look correctly

weather-beaten, and dozens of leather-clad laborers were on their hands and knees, poking dust and dirt into the cracks

between the paving blocks. A line of them went down the sidewalk, busily chewing gum and spitting it out; they were

followed by another crew who carefully placed the wads according to diagrams they carried, and stamped them flat.

Harry set his teeth and muscled his rocking brain into something like its normal position. “I ain’t never seen a day like

this or crazy people like this,” he said, “but I ain’t gonna let it be any of my affair. I got my job to go to.” And trying vainly

to ignore the hundreds of little, hard-working figures, he went grimly on down the street.

When he got to the garage he found no one there but more swarms of stereotyped little people climbing over the place,

dulling the paint work, cracking the cement flooring, doing their hurried, efficient little tasks of aging. He noticed, only

because he was so familiar with the garage, that they were actually making the marks that had been there as long as he had

known the place. “Hell with it,” he gritted, anxious to submerge himself into his own world of wrenches and grease guns. “I

got my job; this is none o’ my affair.”

He looked about him, wondering if he should clean these interlopers out of the garage. Naw—not his affair, He was

hired to repair cars, not to police the joint. Long as they kept away from him—and, of course, animal caution told him that

he was far, far outnumbered. The absence of the boss and the other mechanics was no surprise to Harry; he always opened

the place.

He climbed out of his street clothes and into coveralls, picked up a tool case and walked over to the sedan, which he had

left up on the hydraulic rack yester—that is, Monday night. And that is when Harry Wright lost his temper. After all, the car

was his job, and he didn’t like having anyone else mess with a job he had started. So when he saw his job—his ’39

sedan—resting steadily on its wheels over the rack, which was down under the floor, and when he saw that the rear spring

was repaired, he began to burn. He dived under the car and ran deft fingers over the rear wheel suspensions. In spite of his

anger at this unprecedented occurrence, he had to admit to himself that the job had been done well. “Might have done it

myself,” he muttered.

A soft clank and a gentle movement caught his attention. With a roar he reached out and grabbed the leg of one of the

ubiquitous little men, wriggled out from under the car, caught his culprit by his leather collar, and dangled him at arm’s

length.

“What are you doing to my job?” Harry bellowed.

The little man tucked his chin into the front of his shirt to give his windpipe a chance, and said, “Why, I was just

finishing up that spring job.”

“Oh. So you were just finishing up on that spring job,” Harry whispered, choked with rage. Then, at the top of his voice,

“Who told you to touch that car?”

“Who told me? What do you— Well, it just had to be done, that’s all. You’ll have to let me go. I must tighten up those

two bolts and lay some dust on the whole thing.”

“You must what? You get within six feet o’ that car and I’ll twist your head offn your neck with a Stillson!”

“But— It has to be done!”

“You won’t do it! Why, I oughta—”

“Please let me go! If I don’t leave that car the way it was Tuesday night—”

“When was Tuesday night?”

“The last act, of course. Let me go, or I’ll call the district supervisor!”

“Call the devil himself. I’m going to spread you on the sidewalk outside; and heaven help you if I catch you near here

again!”

The little man’s jaw set, his eyes narrowed, and he whipped his feet upward. They crashed into Wright’s jaw; Harry

dropped him and staggered back. The little man began squealing, “Supervisor! Supervisor! Emergency!”

Harry growled and started after him; but suddenly, in the air between him and the midget workman, a long white hand

appeared. The empty air was swept back, showing an aperture from the garage to blank, blind nothingness. Out of it stepped

a tall man in a single loose-fitting garment literally studded with pockets. The opening closed behind the man.

Harry cowered before him. Never in his life had he seen such noble, powerful features, such strength of purpose, such

broad shoulders, such a deep chest. The man stood with the backs of his hands on his hips, staring at Harry as if he were

something somebody forgot to sweep up.

“That’s him,” said the little man shrilly. “He is trying to stop me from doing the work!”

“Who are you?” asked the beautiful man, down his nose.

“I’m the m-mechanic on this j-j— Who wants to know?”

“Iridel, supervisor of the district of Futura, wants to know.”

“Where in hell did you come from?”

“I did not come from hell. I came from Thursday.”

Harry held his head. “What is all this?” he wailed. “Why is today Wednesday? Who are all these crazy little guys? What

happened to Tuesday?”

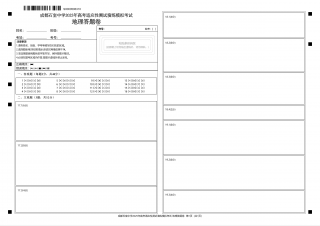

2024-12-06 4

2024-12-06 4

2024-12-06 11

2024-12-06 11

2024-12-06 29

2024-12-06 29

2024-12-06 26

2024-12-06 26

2024-12-06 29

2024-12-06 29

2024-12-06 11

2024-12-06 11

2024-12-06 35

2024-12-06 35

2024-12-06 12

2024-12-06 12

2024-12-06 40

2024-12-06 40

2024-12-06 28

2024-12-06 28

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394