came, he dreamed.

Braun and Maksim slept together for the comfort they took from each other, body touching body.

They shared a deep affection. One might have called it love, if the word hadn’t so many resonances that

had nothing to do with them. Maksim found his loves in Kukurul, young men who stayed a night or two,

then left, others who loved him a longer time but also left.

Brann went through a short but difficult period during the first days they spent on Jal Virri; she

wanted him, but had to recognize the futility of that particular passion. It was a brief agony, but an agony

nonetheless, a scouring of her soul. His voice stirred her to the marrow of her bones, he was bigger than

life, a passionate dominating complex man; she’d never met his equal anywhere anytime in all her long life.

She shared his disdain for inherited privilege, his sar-donic, sympathetic view of ordinary men; her mind

marched with his, they enjoyed the same things, laughed at the same things, deplored the same things,

were content to be quiet at the same time. Anything more, though, was simply not there. She too went

prowling the night in Kukurul, though it was more distraction than passion she was seeking.

There was enough of a nip in the air to make her snuggle closer to Maksim. He grumbled in his sleep,

but again he didn’t wake. She scratched at her thigh, worked her toes, flexed and unflexed her knees. It

was impossible; how did he do it, sleep like that, on and on? She never could stay still once she was

awake. Her mouth tasted foul, like some-thing had died in it and was growing moss. Her bladder was

overfull; if she moved she’d slosh. She pressed her thighs together; it didn’t help. That’s it, she thought.

That’s all I need. She slid out of bed and scurried for the watercloset.

When she came back, Maksim had turned onto his stom-ach. He was snoring a little. His heavy

braid had come undone and his long, coarse hair was spread like gray weeds over his shoulders; a strand

of it had dropped across his face and was moving with his breath, tickling at his nose. She smiled tenderly

at him and lifted the hair back, taking care not to wake him. Lazy old lion. She shaped the words with her

lips but didn’t speak them. Big fat cat sleeping in the sun. She touched the tangled mass of hair. I’ll have a

time combing, this out. Sorceror Prime tying granny knots, it’s a disgrace, that’s what it is. She patted a

yawn, crossed to the vanity he’d bought for her in Kukurul a few years back.

The vanity was a low table of polished ebony with match-ing silver-mounted chests at both ends and

a mage-made mirror, its glass smooth as silk and more faithful than she liked this autumn morning. Maybe

it was the green light, but she looked ten years older than she had, last night. She leaned closer to the

mirror, pushed her fingers hard along her cheekbones, tautening and lifting the skin. She sighed. Drinker

of Souls. Not any more. I don’t have to feed my nurslings now. They’re free of me. She stepped back

and kicked the hassock closer, sat down and began brushing at her hair. There was no reason now for

the Drinker of Souls to walk the night streets and take life from predators preying on the weak. The

changechildren could feed themselves; they weren’t even children any more. They came flying back once

or twice a year to say hello and tell her the odd things they’d seen, but they never stayed long. Jal Virri is

boring; Jay said that once. She paused, then finished the stroke. It’s true. I’m petrified with boredom.

I’ve outlived my useful-ness. There’s no point to my life.

She set the brush down and gazed into the mirror, exam-ining her face with clinical objectivity,

considering its planes and hollows as if she were planning a self-portrait. She hadn’t been a pretty child

and she wasn’t pretty now. She frowned at her image. If I’d been someone else looking at me, I’d have

said the woman has interesting bones and I’d like to paint her. Or I would have liked to paint her before

she started to droop. Discontent. It did disgusting things to one’s face, made everything sag and put sour

lines around the mouth and between the brows. Her breasts were firm and full, that was all right, but she

had a small pot when she sat; she put her hands round it, lifted and pressed it in, then sighed and reached

for the brush. It won’t be long before I have to pay someone to climb into bed with me. She pulled the

bristles through the soft white strands. Old nag put out to pasture, no one wants her anymore.

She made a face at herself and laughed, but her eyes were sad and the laughter faded quickly. Might

as well be dead.

She rubbed the back of her hand beneath her chin and felt the loosening muscle there. Death?

Illusion. Give me one man’s lifeforce and I’m young again. Twenty-four/five, back where I was when

Slya finished with me. No dying for me. Not even a real aging, only an endless going on and on. No rest

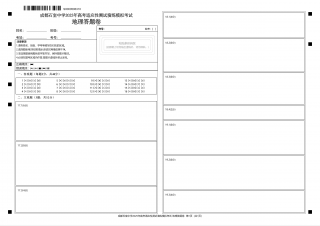

2024-12-01 6

2024-12-01 6

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 4

2024-12-01 8

2024-12-01 8

2024-12-01 30

2024-12-01 30

2024-12-01 23

2024-12-01 23

2024-12-01 17

2024-12-01 17

2024-12-01 9

2024-12-01 9

2024-12-01 13

2024-12-01 13

渝公网安备50010702506394

渝公网安备50010702506394